Culture / Global

Life in miniature

The bigger the better, right? Wrong, according to the artists, directors and publishers finding ways to reach more engaged audiences with postage-stamp-sized paintings, television shows for smartphones and small print runs of books about very niche topics.

01.

Small art

Pocket-sized paintings are big news. What’s behind the appeal of small sketches?

From her studio in north London, Anj Smith paints dreamlike landscapes and melancholic women. In technique and style, her intense pieces recall the intricacy of Hieronymus Bosch. But unlike the Dutch master’s triptychs, many are tiny – in some cases as little as 20cm wide.

Smith is one of a growing number of artists finding big success with small works. Ridley Howard paints tender images of lovers, while fellow New Yorker Maureen Gallace specialises in landscapes – both on a micro scale. Even abstract painting – a form associated with the monumental since Jackson Pollock exhibited his massive drip-painted panels – is beginning to downsize.

Rising stars such as the Brazilian Lucas Arruda, Venezuelan Alvaro Barrington and American Ryan Nord Kitchen have all begun to experiment with working in smaller formats but the results have still had a huge impact.

Size has always mattered in art and larger works have often been the most fawned over. So how have collectors and curators developed a penchant for the petite?

Roberta Smith, an art critic at The New York Times, has written that “work that you can take home in a taxi” has become a way to challenge an art world that has for too long fetishised the extra-large.From Art Basel’s Unlimited (the Swiss fair’s section dedicated to the gargantuan) to the Tate Modern’s enormous commissions for its Turbine Hall, spectacular pieces have repeatedly proved their pulling power. Yayoi Kusama’s Infinity Mirrored Rooms are such a draw that Victoria Miro, the normally sedate commercial gallery hosting her exhibition in London, was forced to issue tickets to control numbers.

Artists’ studios have often grown to cater for the creation of large-scale works, with many choosing to employ dozens of assistants. But for some this overblown approach has quashed a fundamental part of the creative process.“We are seeing a return to individual making – and scale is part of that,” says Zoe Sperling, director of the London outpost of international gallery Hauser & Wirth. “Collectors like the jewel-like quality of small art and the personal connection with the work. It is gaining momentum in our over-saturated visual world.”

Smaller work can be more accessible for buyers too: it is easier to display and often more affordable. But demand at the top end of the market is also growing. Small-scale work is now prized by collectors who are not restricted by the size of their exhibiting space – nor their pocketbook.

Anita Zabludowicz is a collector for public art spaces in London and New York. Her acquisitions include some of the biggest names of the past 20 years, from American painter Richard Prince to French multimedia artist Pierre Huyghe. But her London mansion is filled with tiny ceramics; small paintings and photographs are scattered across corridors, bathrooms and stairwells.

“We have large walls and lots of light so I started with big paintings and photographs,” she says. But she soon became seduced by the allure of the miniature. “Some works command a stage without taking up very much space.” Zabludowicz, it emerges, is an Anj Smith fan. “If you asked me what I would save in a fire, of all the art I have, it would be her paintings.To me they are so beautiful. They are such precious things.”

02.

Small television

Forget the silver screen, film-makers are chasing time-strapped phone users.

Step on public transport and you’re bound to spot a passenger with a phone propped on their lap, earphones in, eyes glued to the screen. They won’t waste a minute of their commute playing Candy Crush. Long gone are the days when a large screen was needed to watch television; thanks to smartphones, the small screen has become a whole lot smaller.

As ever the medium influences the message: even the most determined viewers will struggle to follow a two-hour historical drama on a 12cm display. Short-form shows suit the small screen but an audience used to Netflix nailbiters expects more from short videos than clips of skateboarding bulldogs. Facebook, Instagram and YouTube might have helped to create an appetite for mobile video but 2019 will be the year that short-form goes premium.

The effort is being led by Jeffrey Katzenberg, the former Walt Disney Studios chairman and Dreamworks Animation ceo. Along with former Ebay and Hewlett-Packard CEO Meg Whitman, Katzenberg has created Quibi (short for “quick bites”), a platform dedicated to short-form content. Having raised $1bn (€873m) from investors including Hollywood studios, global broadcasters and Chinese technology giant Alibaba, Quibi is expected to launch next year.

“The trends are clear,” says Katzenberg. “Mobile video consumption is exploding, with the average consumer now spending about 60 minutes [per day] watching mobile video, up from just six minutes in 2012. There is a clear white space for premium content in mobile video that is of the same quality as what you would find at a movie theatre.” Quibi has already enlisted several A-list contributors: The Shape of Water director Guillermo del Toro is making a zombie story; thriller specialist Antoine Fuqua is preparing a modern take on 1970s classic Dog Day Afternoon; and producer Jason Blum is working on his Fatal Attraction-esque Wolves and Villagers.

For film-makers, this may feel like a completely new approach but writing a short-form series is close to the way that shows were made for cable television. “Quibi brings together the storytelling used to deliver a two or three-hour story arc with the discipline of ‘act breaks’, which writers have had to use to deliver network television against time increments to allow for advertising,” says Katzenberg.

Quibi will initially launch in the US but the company has plans for expansion across the globe: it hopes to develop projects with foreign auteurs, even producing non-English-language shows.

For many investors in the project, jumping on board was a no-brainer. “Smartphone screen use is exploding,” says Darren Throop, CEO of Entertainment One, the company behind The Walking Dead and a Quibi investor. “Being in the market with high-quality content is something that needs to be explored and done.” All3Media, the UK production company behind the BBC's Call the Midwife and Fleabag, is also eyeing plans to work with the nascent platform. “We’d love to produce for Quibi,” says CEO Jane Turton. “We’re testing, we’re watching and participating. It will be fascinating to see how it goes.”

Quibi is unlikely to be alone in the marketplace. In October, Snapchat unveiled its first spate of original short-form programming, including college coming-of-age series Co-Ed, which is produced by the Duplass Brothers. It is also remaking Bref, a French series of episodes that last an average of two minutes and debuted on Canal+.

The world’s leading streaming services are also weighing in. Netflix has teamed up with Buzzfeed to produce short-form documentary series Follow This and has ordered new episodes of Jerry Seinfeld’s Comedians in Cars Getting Coffee. Amazon is funding shorts from comedy website Funny or Die while Facebook Watch is ordering documentaries from a raft of producers including Barcroft Media, a heavy-hitting YouTube channel. Traditional broadcasters are also getting in on the action. BBC Studios has opened a new investment fund dedicated to bolstering high-end short-form projects, aiming to produce scripted series with a whopping budget of £500,000 (€562,000) per each 15-minute episode. The opportunity seems good enough to justify throwing money at the genre but some smaller foreign-language producers are more cautious. Israel’s Armoza hopes that its Hebrew-language short-form series Instababe will be an international hit but, for CEO Avi Armoza, there is no guaranteed revenue stream. “There is a contradiction: the business models are not clear,” he says. “It is crucial to reach young audiences where they are and they are often on a platform like Instagram.”

For any nascent platform, finding a space in a market dominated by social-media giants will be a challenge. High-profile players, such as NBCUniversal and Verizon, saw burgeoning short-form platforms fail in 2018. Can the stature of the enlisted cast and crew make the difference for Quibi? “When we speak with top-tier creatives about Quibi, they immediately get it,” says Katzenberg, who remains confident. Time-strapped viewers hungry for short, sharp bursts of well-produced video might do too.

03.

Small print runs

Crowd-funded books about increasingly niche subjects find a fervent audience.

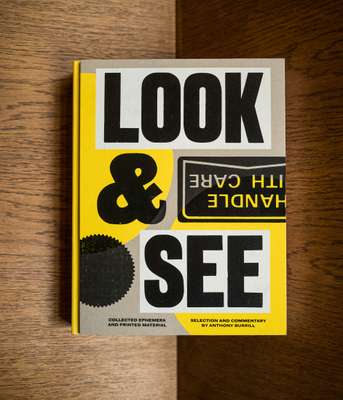

Fancy reading about the history of Japansoft, the Japanese video-game movement in the 1980s and 1990s? Or taking a tour through the colourful ice-lolly packets and plane tickets that inspire British graphic designer Anthony Burrill? Maybe you’d prefer to see Ralph Waldo Emerson’s Self-Reliance repackaged as a “typographic essay” by Dutch designer Irma Boom? Perhaps not. But there is almost certainly an audience that is intensely interested in each of these subjects. Rather than hunting a mass-market bestseller, these are the audiences that some large publishing houses hope to reach with small print runs.

Volume, an offshoot of London-based publisher Thames & Hudson, uses crowd-funding to produce illustrated books on niche topics that would otherwise struggle to make it onto the page. Its first title Look & See – about Burrill’s inspirations – was released in November. Its platform is the work of Lucas Dietrich and Darren Wall, a dynamic duo with complementary skillsets. “Old-school publishing guy” Dietrich is international editorial director at Thames & Hudson; he brings editing clout to the project. As an art director who founded Read-Only Memory, an online company specialising in books about video games, Wall adds the design and digital nous.

They’re using a funding model normally reserved for start-ups to make books on topics that would usually be too risky for a big house such as Thames & Hudson to publish. “The commissioning spirit at Thames & Hudson is very entrepreneurial,” says Dietrich. “But it is also a publishing company that’s 70 years old. Launching this satellite was its chance to try something different.”

Dietrich and Wall accept submissions for books at any stage of development: the seed of an idea, a working script or a finished book by a publisher short of funds. Once selected, Volume creates mock-ups of covers and a blurb, posts the potential book on a slick website, and opens to backers. The only sunken cost is Dietrich and Wall’s time. “You’re ‘de-risking’ the book because everything is paid for upfront,” says Dietrich. “If it turns out there’s not a big enough market for, say, basket-weaving, then we don’t make that book,” adds Wall. But this will rarely be the case, according to Dietrich. “We only need to do a print run of 1,000 copies to make a book viable – and I believe we can sell 1,000 copies of pretty much anything.” Using traditional models, a publisher such as Thames & Hudson would need to sell at least 5,000 copies to make a title worthwhile. Dietrich and Wall lean towards subjects that have a fervent following: graphic design; video games; pretty much anything Japanese. Books with a person at the centre are much more likely to ignite passion than those that deal with general trends. Unusual topics are brought to life with eye-catching covers.

“I get so depressed when I walk into most bookstores,” says Dietrich. “Everything looks the same.” That’s not to say that Volume will revolutionise the industry on its own but it has started to fill small yet significant gaps. “If this is not the future it’s certainly one of the more interesting paths,” says Dietrich. “It attracts younger talent in terms of submissions and, with the funding model, engages readers from the outset. They get so emotional about books. We want to maximise that emotional attachment.”