Manufacturing / Scotland

Soft centre

The small town of Hawick might not be a name that’s readily associated with high fashion but its long-standing knitwear industry has won it a global reputation as a place of expert artisanship and the finest yarns. Just ask the international luxury houses investing in its future.

When it comes to international hubs of luxury fashion manufacturing, certain cities or regions spring to mind. Paris is known for haute couture, while Milan, the birthplace of high-end hat-making (ever wondered where the term “milliner” comes from?), remains a key component of northern Italy’s rich textile-making industry. Lesser known is Hawick in Scotland but, as the sign that’s posted on the small town’s border suggests, this is a world capital of top-tier cashmere manufacturing.

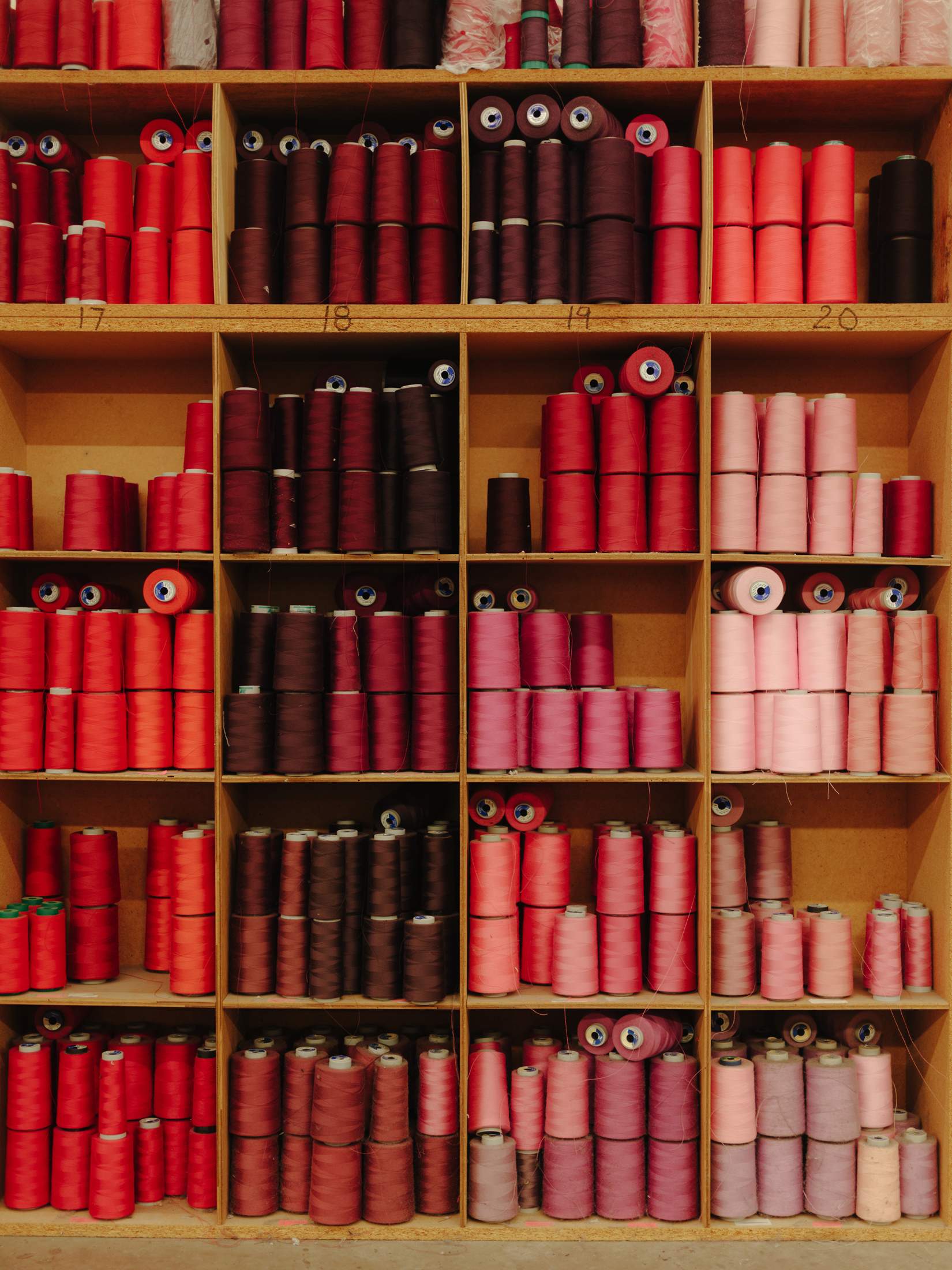

Selection of threads

An hour and a half’s drive south of Edinburgh, at the confluence of the rivers Slitrig and Teviot on the nation’s southern border, Hawick has been a hub for clothes making since the 1700s. Today it’s a global go-to for the production of cashmere knitwear; the goat’s hair from which it is made is more weather resistant, lighter and warmer than that of a sheep. Many businesses make their own wares, including well-known brands such as Barrie, Hawico and Johnstons of Elgin. Their books are balanced by producing white-label cashmere garments for continental fashion houses, including Prada, Dior, Hermès and Chanel.

“Coco Chanel used to fish in the rivers here,” says Clive Brown, commercial and development director at Barrie, which was acquired by Chanel in 2012. “She found inspiration here and would come to Scotland a lot.” Founded in 1903, Barrie was an established mill when Chanel visited the region in the 1920s but it wasn’t until 1984 that they first worked together. That was when Barrie, then just a knitwear-maker, became Chanel’s cashmere producer of choice. For the French fashion house, Hawick’s woollen products and workers were regarded as the world’s best, offering the softest yarns and most skilled artisans, who were reared on the craft. Today, Barrie has harnessed its partnership with Chanel to grow its own eponymous label. As The Forecast tours its factory, workers – some of whom are third-generation employees – cut, stitch and sew scarves, jumpers and cardigans. Their attention to detail is meticulous and, despite machine assistance, the human touch is in evidence everywhere. “Our knowledge lies in the handcraft and methods that have been passed down by families through the generations,” says Brown.

These skills, such as the workers’ ability to identify the precise moment when a garment has been washed for the correct length of time, has helped Hawick to retain its reputation. It was also a factor in attracting the area’s current largest employer, 224-year-old Johnstons of Elgin, to move to the town. Originally a weaving company from the north of Scotland, it set up in Hawick in 1980 with a plan to expand into knitwear. “We were looking for a skilled workforce of people who could do the handwork on the knitting,” says Nick Bannerman, Johnstons’ global sales director. The company, which has a cashmere label of its own that’s considered an international luxury brand, also produces for a host of continental couture houses. “Our own brand represents about a third of our business, while the rest is private label serving a lot of the big houses,” says Bannerman. “We’ve had long relationships with them.”

“Our knowledge lies in the handcraft and methods that have been passed down by families through the generations”

These relationships have stayed the course, even in the face of increasing competition from Italy and Asia. Bannerman explains that Hawick’s endurance as a manufacturing base comes down to the purity and quality of its products. Italian cashmere is often knitted in a slacker way, while Asian cashmere might feel softer when it’s first worn but its quality can falter after multiple wears. Scottish cashmere is more tightly knitted and, for Bannerman, this is crucial. It results in items becoming more supple over time, lasting longer, holding their shape and resisting pilling. “What makes cashmere a luxury is that it should last,” says Bannerman. “Buying cashmere pieces should be an investment; the sort of thing that can be passed down from your dad to you and from you to your children.”

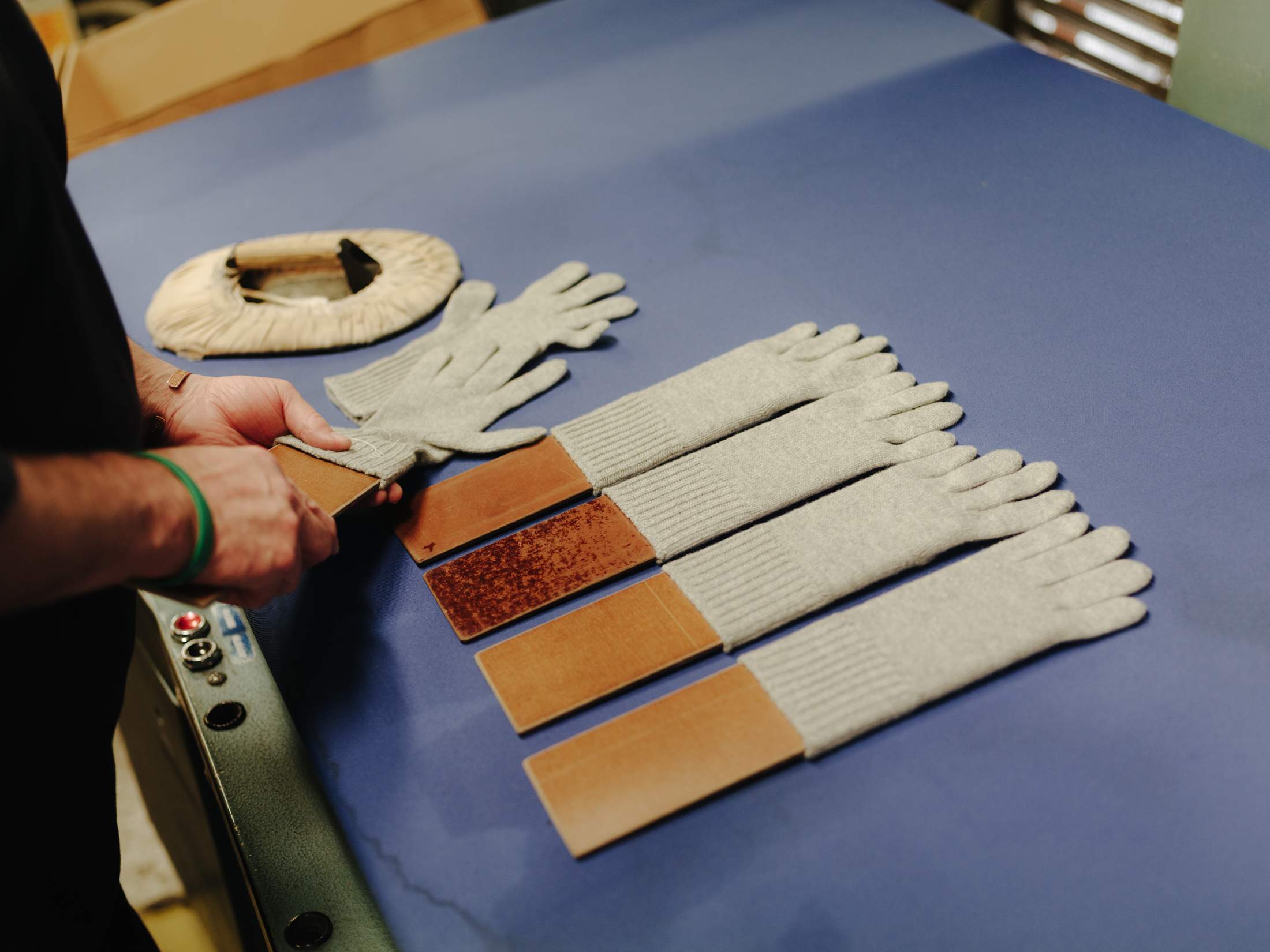

Checking sizes

Fine cashmere scarves

Not too long ago, the future of luxury fashion manufacturing in Hawick looked shaky. A downturn in the late 1980s and 1990s, in part due to international competition, resulted in work drying up and many makers, including Pringle of Scotland and McGeorge, closing or selling off their production facilities. But with Chanel’s investment in Barrie a decade or so later, and the rise of a more quality-conscious consumer across Europe, Hawick’s future as a manufacturing hub seems secure. Heritage brand Scott & Charters recently opened a factory in the town, while Barrie has established a trainee school with the capacity to take on 20 new pupils at a time – some of them the children of existing workers.

Hawick is reaping the benefits of striking the right balance between local entrepreneurship and foreign investment. “The big thing for Chanel was to save the knowledge, workmanship and handcraft for the future,” says Barrie’s Brown. “And it wasn’t just for them but for the whole of the couture and luxury industry. They couldn’t allow these skills to die.”