New frontiers / Global

Making the cut

The landscape of the furniture industry is changing: global supply chains are strained, making access to materials difficult and consumers are demanding products that enhance their wellbeing by being designed, produced and supplied transparently. We profile five brands rising to these challenges.

Part & Whole

Making repairable furniture

Canada

“A sofa is this large piece of furniture that you typically only buy a couple of times in your life. It’s almost more in line with buying a car,” says Guy Ferguson, brand director of Canadian furniture company Part & Whole. It was this realisation that led Ferguson, who co-founded the Victoria, British Columbia-based firm in 2018, to try to solve the more cumbersome conundrums that can be associated with the mass-manufacture of sofas.

“A typical sofa is massive and bulky, and one of the main failure points on a piece of furniture like this is suspension,” he says. “Eventually, with use, that suspension – either springs or woven – will begin to fail, and then that entire product is likely to end up in the garbage or be very costly to rebuild.”

Responding to this challenge, Part & Whole has designed modular sofas (its first piece, named Total, was made available in 2021 after a four-year development process) that can be broken down into component parts, including its laser-welded steel frames, down cushions and wool upholstery. “Every part can be replaced; everything can be serviced or disposed of in the correct way,” he adds. “This is all with the intention of creating objects that can be kept in use, to principles of circular design and manufacturing.”

Not only can you expect Part & Whole to continue with this philosophy (its newest work, Chord, riffs on the colourful, rippling surfaces of 1970s sofa designs) but for boutique furniture-making to follow suit. “It’s a sector that makes objects that need a lot of specialised expertise. As a result, it hasn’t been able to move at the pace of other industries in terms of circularity and repairs,” says Ferguson. “But it’s going to start changing quite quickly.”

partandwhole.com

Mabeo Furniture

The designer as the middleman

Botswana

Gaborone-based designer Peter Mabeo is known for creating furniture inspired by Botswana’s rich craft tradition. But his approach hasn’t always been so rooted in his homeland’s culture. “Back when we started in the early 1990s, there was no historical reference to craft within the local commercial context,” says Mabeo. “My early work was about trying to meet someone’s expectations on boring, commercial projects.”

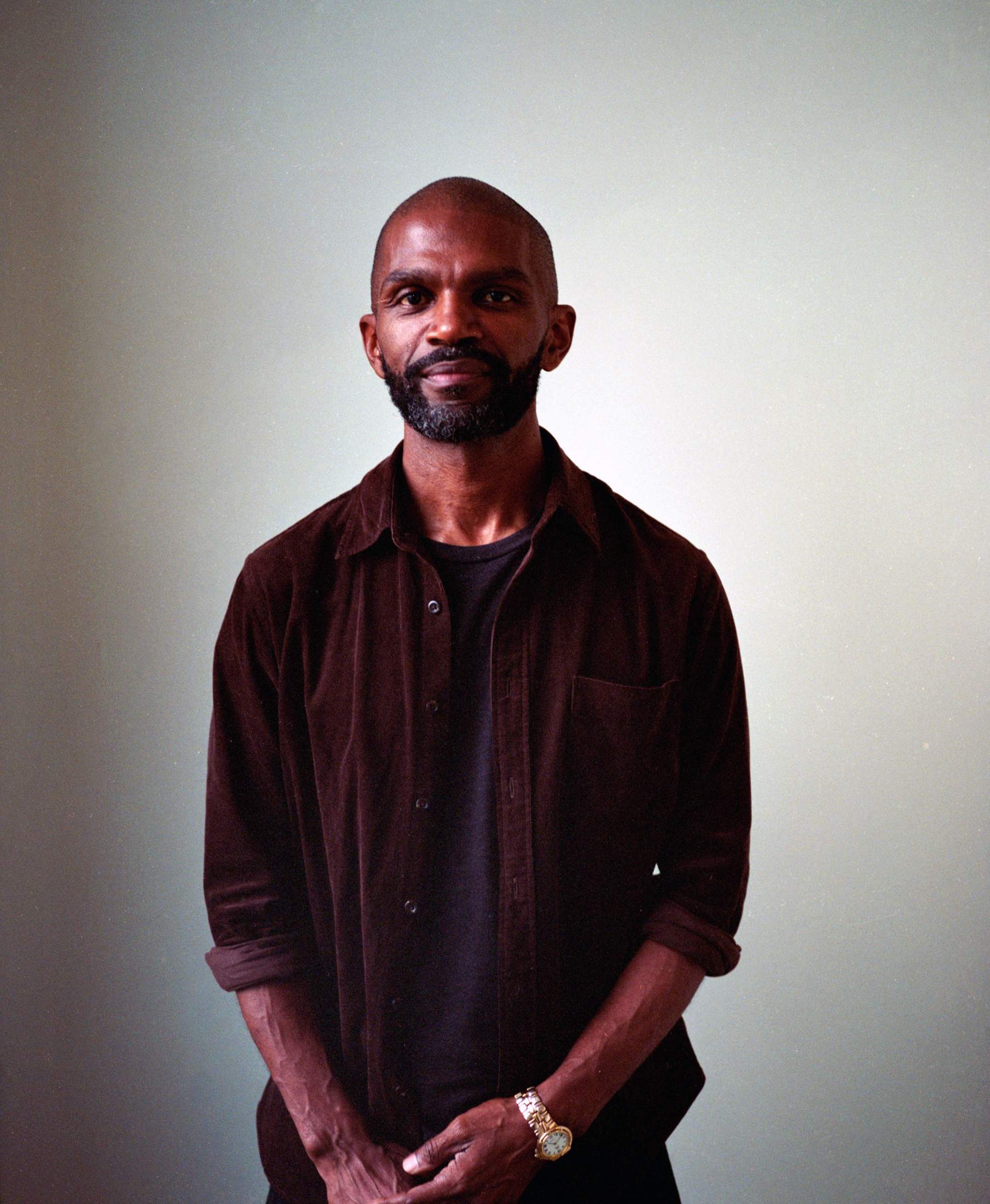

Convinced that there was a more inspiring way to practice in the southern African country, Mabeo (pictured) set a new agenda for his studio. “I decided to forget about that commercial way of working entirely and do something that felt more aligned with Botswana’s culture and the way we work.”

The result? A business model that has seen him act as a middleman of sorts, pairing his knowledge of local craftspeople’s skills with client briefs. And while Mabeo knows that this is good for the region’s creative industry, he stresses that it is financially savvy too. Today, Mabeo Furniture is a multidisciplinary company collaborating with the likes of Fendi and exporting southern African design globally. “The idea is not to help from the superior position that is often associated with design but to collaborate using design as a tool for mediation,” he says.

It is a reminder that furniture-makers don’t need to look to established business models. Instead, forging connections between local craft and clients can be a profitable way forwards too.

mabeofurniture.com

Reframed

Flatpacking the future

Denmark

“I’m trying to make good design accessible because I believe that people’s lives are better when they’re surrounded by good interiors,” says Kasper Simonsen, founder of Copenhagen-based bed-maker Reframed. The firm has been working to spice things up in the bedroom since its foundation in 2021, offering smartly designed furniture at an accessible price point.

“I was living in London and my friends were buying flatpack furniture that wasn’t made on the continent, meaning that it would spend 40 weeks on a boat before coming to Europe,” says Simonsen. “Or if they were buying high-end designs, they would have to go to the retailers and wait eight weeks for delivery.” Reframed’s business model, Simonsen says, fights these inefficiencies.

Its bed frames are made from aluminium extrusions produced by Norsk Hydro in Sweden, whose clients include Rolls-Royce and which uses 82 per cent post-consumer recycled aluminium. They are then machined and powder-coated in Denmark. The lightweight frames are flatpacked and shipped to customers in less than a week; tension locks built into the frame ensure that the bed can be assembled in minutes, without screws.

Reframed focuses on connecting with customers and ensuring that its designs are simple. “A customer called me and said that he was putting together his bedroom but couldn’t find the bed’s screws,” says Simonsen. “I told him that was the point: no screws, just the locks. He called back and when I asked how it went, he said ‘Great – until we had to assemble an Ikea chest of drawers.’”

reframedbrand.com

One For Hundred

Replenishing raw materials

Austria

In 2015, Anna and Karl Philip Prinzhorn swapped their flat in central Berlin for a house in the middle of an Austrian forest in Weinviertel, one hour from Vienna. “It’s so remote: there is no phone signal,” says Anna, a Vienna-born industrial designer who returned to the country with her husband and two daughters after 10 years abroad.

Karl Philip’s family has owned the forest for about two centuries; it is a dense thicket of white oak, larch, spruce, ash, maple and walnut trees that sprawls across 900 hectares. “When we arrived here I decided that it was time for me to launch my own project,” says Anna. “And it would have been stupid not to work with wood, because it was all around me.”

The result is One For Hundred, a furniture brand that uses wood felled in the forest to create a range of made-to-measure tables, sideboards, benches and shelving. But the brand is notable for more than just its commitment to sourcing timber from nearby; for each product purchased, the Prinzhorns plant 100 trees. “It wasn’t enough for me to just work with a sustainable resource,” Anna says. “I want to build up the resources I’m using. As designers, we can’t go on just producing new stuff. We want to be disruptive and come up with innovative concepts. And customers want transparency and honesty.”

Before moving to Berlin, the couple lived in New York, where Anna worked for designer Stephen Burks. “His way of thinking had a real effect on me,” she says. “He was always pushing the envelope and trying to change the industry.” While her time spent working with Burks helped shape One For Hundred’s pioneering ethos, Anna learnt to work with wood in Berlin. There she teamed up with two architect friends to launch Bullenberg, a brand selling custom oak tables. They ran the firm for three years before Anna left and launched One For Hundred with Karl Philip. “There was a lot to learn from him,” she says. “You need about two years after felling the tree until the wood is ready to use. The trunks are cut into planks in the winter dormant period and then they are stored. And you have to make sure that there are no worms or fungi that will damage it during this process.”

Once drying is complete, One For Hundred’s wood is taken on a 90-minute drive into the Czech Republic, where a carpenter realises the designs. “I’ve been working with her from the beginning. She is a third-generation carpenter who is super-skilled with solid wood,” says Anna, adding that One For Hundred’s designs place an emphasis on timelessness and minimalism. If there is a shortage of dry wood from the forest, the brand buys it from the regional dealer that it sells its own wood to, ensuring that it has control over the quality and origin of the material that’s being used for its pieces. “I never wanted to reinvent the wheel. I’m all about removing the ego from design and creating objects that last for generations. What is trendy in 2022 probably isn’t going to be cool in 2030.”

oneforhundred.com

Light Cognitive

Enhancing our wellbeing through good lighting

Finland

When Sami Salomaa returned to his native Finland after decades overseas, he noticed the powerful effect that light – or the lack of it – can have on people; the long summer with its white nights made Finns happy but in the winter, with only a few hours of sunlight, people appeared gloomier. Salomaa (pictured, on left, with colleagues) also observed that there had been little innovation when it came to led lighting design. A physicist and mathematician by training, he studied and experimented with artificial light, looking at how it could resemble mood-boosting natural light.

The fruits of Salomaa’s research are apparent in Light Cognitive, the company he launched in 2014. Its panels, using led technology, produce a light whose quality and feel are similar to natural light. This has many benefits. “People feel better, colours look the way they are supposed to look and indoor spaces feel more natural,” says Salomaa, listing just some of the reasons why the likes of Zara, Fendi and Hôpital de la Tour in Meyrin, Switzerland, have opted for his brand’s creations.

To achieve the desired effect, the company’s innovative lighting panels have been designed to replicate nature’s circadian rhythm and improve behaviours such as alertness, cognitive performance and sleep. “I’d like to think that people don’t feel like they are looking at a light, but instead get the same feeling as when gazing at the horizon on the beach,” says Salomaa.

With this in mind, perhaps it’s time for designers and architects to think about the holistic way in which lighting affects humans. Embracing Light Cognitive’s work is a good place to start.

lightcognitive.com

photographers: Alana Paterson, Jan Søndergaard. images: OMO Creates, Illustrative Options, Ruan Van Jaarsveldt