Made in the shade / United Arab Emirates

City planning

From parks to design initiatives, here’s what makes a dynamic, liveable country.

Masdar City

Constructive thinking

Masdar City in Abu Dhabi is a prime example of sustainable building in cities. A laboratory for future urban development, the low-carbon community has popped up by the airport over the past decade and is a pioneer in clean energy. Green technology is the order of the day and the initiative aims to support the uae’s transition from oil towards a more knowledge-based economy. Masdar City is also intended to be a blueprint (they call it a “greenprint”) for future cities in terms of energy and water efficiency, mobility and the reduction of waste. Anchor tenants, including Siemens, the Emirates Nuclear Energy Corporation and Honeywell, benefit from technologies such as onshore and offshore wind power, solar, carbon capture, waste-to-energy, water desalination and thermal energy storage.

masdar.ae

Expo 2020’s legacy

Long-term success

We all know how much fun an expo can be for the six months that it attracts visitors and wows residents (see page 26). But what legacy should it leave the host city? Well, Dubai has a proposal. The Dubai 2040 Urban Masterplan is an outline of where the emirate thinks it should be in 20 years.

The idea is to divide the space into five areas of development, and the district earmarked for Expo 2020 is one. More than 80 per cent of what is being used for the event will remain and be converted into a mixed-use business and residential neighbourhood. The mobility, sustainability and opportunity pavilions, two parks and water features will be transformed into tourist attractions, while the rest will contain affordable housing and become a focus for exhibitions, tourism and logistics.

UAE 101

Cultural quandaries

Curious souls seeking to understand the nuance of life in the uae should grab a copy of Roudha Al Marri and Ilaria Caielli’s book, uae 101, illustrated by Reem Al Marri. This collection of 101 tales – about everything from the nation’s founding to its folklore, falcons and farming – poses many questions. Are all Emiratis wealthy? What’s a khushmck? And what can’t I joke about? It answers them gracefully too. What the book does best is capture a young and fast-changing nation with a rich history. Required reading, if you ask us.

Mina Zayed

Harbour mastered

The Mina Zayed port development is a 3 million sq m mega-project, which includes an extensive renovation of the city’s former port and wharf, bringing together all the city’s souks – fish, fruit and vegetables, dates, meat, wholesale and carpet – in one place, along with a walkable warehouse district with plenty of shade, greenery and mixed-use spaces. The Warehouse421 gallery is already showing what can be achieved here and offering some hints about how this human-scale area is set to spring forth. Watch this space.

Local knowledge

People of the UAE

“Local” can be a blunt word but in the uae the term means Emiratis, who constitute just 11 per cent or so of the population of a little under 10 million. Expats from India and Pakistan represent about 40 per cent, with the rest comprising people from more than 200 nations. Yet many who live or were born here but can’t trace their ancestry back to the land are not citizens. Steps to address this, such as the golden visa scheme – which allows for long-term residency – and removing the need for locals to own majority stakes in companies, are moves in the right direction.

Green space

Balance of nature

For an arid landscape, the uae doesn’t do badly for green space. Its native mangroves, from Abu Dhabi to Sharjah, are protected and honoured, and urban respite is easy to find too: just look at Dubai’s manicured 64-hectare Safa Park and Umm Al Emarat in Abu Dhabi, which has a running track and amphitheatre. Inroads are also being made in developing greenbelt land to help nature thrive. And although you’re still never far from pristine grass or well-watered trees, there’s a new onus being placed on using native species rather than imported ones. Designed by sla architects, Al Fay, also in Abu Dhabi, veers away from imported ideas of beauty to offer a home to 2,000 indigenous plants without running up anything like the water bill you would imagine. Expect to see plenty more ghafs (the nation’s native tree) and markh shrubs (also called broom bushes) as the idea begins to take seed.

Political landscape

Nation building

Landing in Abu Dhabi or Dubai airport, it won’t be long before you spot a portrait of Sheikh Zayed bin Sultan Al Nahyan, smiling wistfully and usually wearing a ghutrah (traditional headdress). In 1971 the “Father of the Nation” helped to pull together the seven sheikhdoms of the former Trucial States into what became the United Arab Emirates. The Abu Dhabi native served as the nation’s ruler until his death in 2004, to be succeeded as president by his son, who remains in power. As visible as the reverential portraits are the fingerprints that Sheikh Zayed’s rule left on the nation, mainly in terms of its tolerance to new ideas and other ways of thinking. Today his name and image can be spotted on everything from road names to foundations and even school notebooks. Sheikh Zayed was an active and thoughtful ruler who laid the foundations for many aspects of the country’s dizzying development in everything from healthcare to literacy. Today the seven emirates are ruled by royal families drawn from the initial sheikhdoms involved in the unification. By convention, the president is from Abu Dhabi while the prime minister hails from Dubai, though power is gained by appointment rather than election.

Public transport

On the move

The uae’s increasingly popular public transport system includes metro, monorail, tram, bus and ferry. The Dubai Metro, for instance, now stops at the Expo site and has women and child-only carriages. Abu Dhabi has scenic water taxis that bolster its bus, bike and e-scooter services. Dubai ride-hailing app Careem is also useful.

Alserkal Avenue

A study in walkability

Alserkal has become a byword for the uae’s ability to achieve what many said it couldn’t: zoned, shaded and walkable street life with an organic, unfussy atmosphere. In short, not another mall. This once drab corner of industrial Al Quoz has changed exponentially in the decade since a clutch of warehouses and lock-ups were cleaned up to the point that Dubai’s blue-chip gallery world decided to make it their home. Alserkal is now a one-stop shop for great art, excellent coffee served in buzzing surroundings, and an intriguing nightspot, called The Fridge. It has all been enabled by some great architecture (Rem Koolhaas’s Oma worked on multidisciplinary venue Concrete) but really achieved by good tenants who know the value of walking around the block – with art lovers, design aficionados and coffee nuts – to show off the neighbours’ talents (see here).

Dubai Design District

Joined-up thinking

Before the Design District opened, we were sceptical of the idea of simply commissioning a space where design-minded companies in architecture, fashion and the culture industries would flock. Trying it in London or New York would be like herding cats. Businesses in these industries, though, are afforded favourable rates by being part of a free zone. Just south of Downtown Dubai, it’s home to about 1,000 offices, cafés, 100 shops and restaurants and some budding young studios that are shaping spaces in the uae and beyond. Sometimes called “d3”, the district broke ground in 2013 and was completed in 2019. It constitutes 11 low-rise buildings and breezy, walkable thoroughfares with plenty of shade, plus a calendar of events and exhibitions. It all works rather well.

dubaidesigndistrict.com

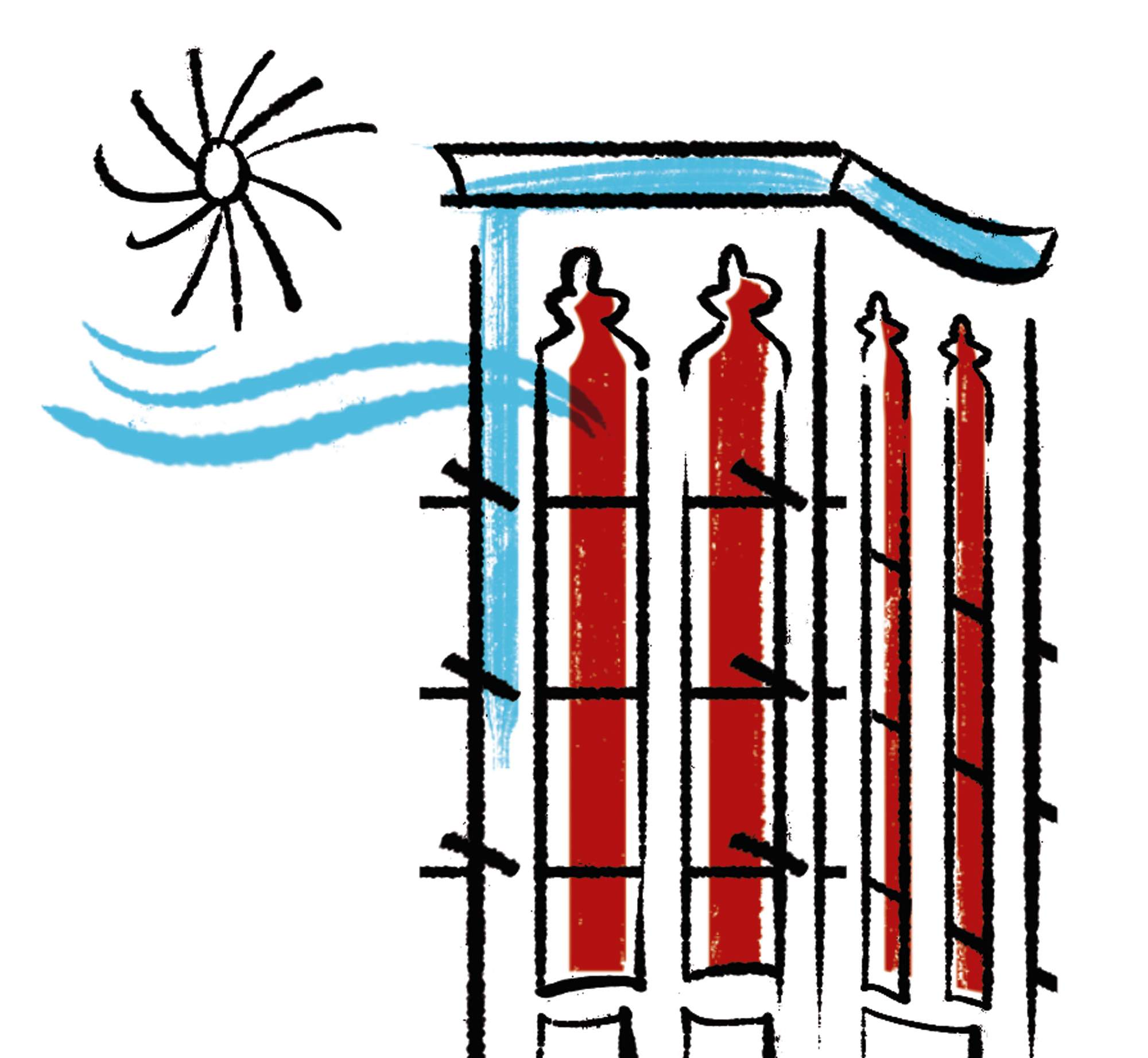

Holding water

Cool heads

There’s not much water around but the uae’s use of desalination has kept the taps running. It has ambitious plans for water security by 2036 through using the scant resource more efficiently. The region’s traditional architecture, from wind towers to the use of shade, could inform cooler buildings in a warming world too.

Qasr Al Hosn

Pride of place

This square in downtown Abu Dhabi exemplifies the key developments in the nation’s built environment and the more thoughtful manner in which it’s creeping forward. Abu Dhabi’s oldest stone building, originally built to guard the city’s only freshwater well, Qasr Al Hosn fort (below) dates from 1761 and is the ancestral home of Sheikh Zayed. A few steps to its east is the low-slung, modernist-influenced masterpiece of the city’s Cultural Foundation, completed in 1981. At the square’s northern corner sits the 2019 Cebra-designed Al Musallah prayer hall (above), a contemporary take on religious architecture built from irregular geometric shapes. Surrounded by wide, leafy boulevards and the thriving downtown drag, this is the sort of careful preservation and sensitive intervention that honours the past with a nod and a wink to the future. Bravo.

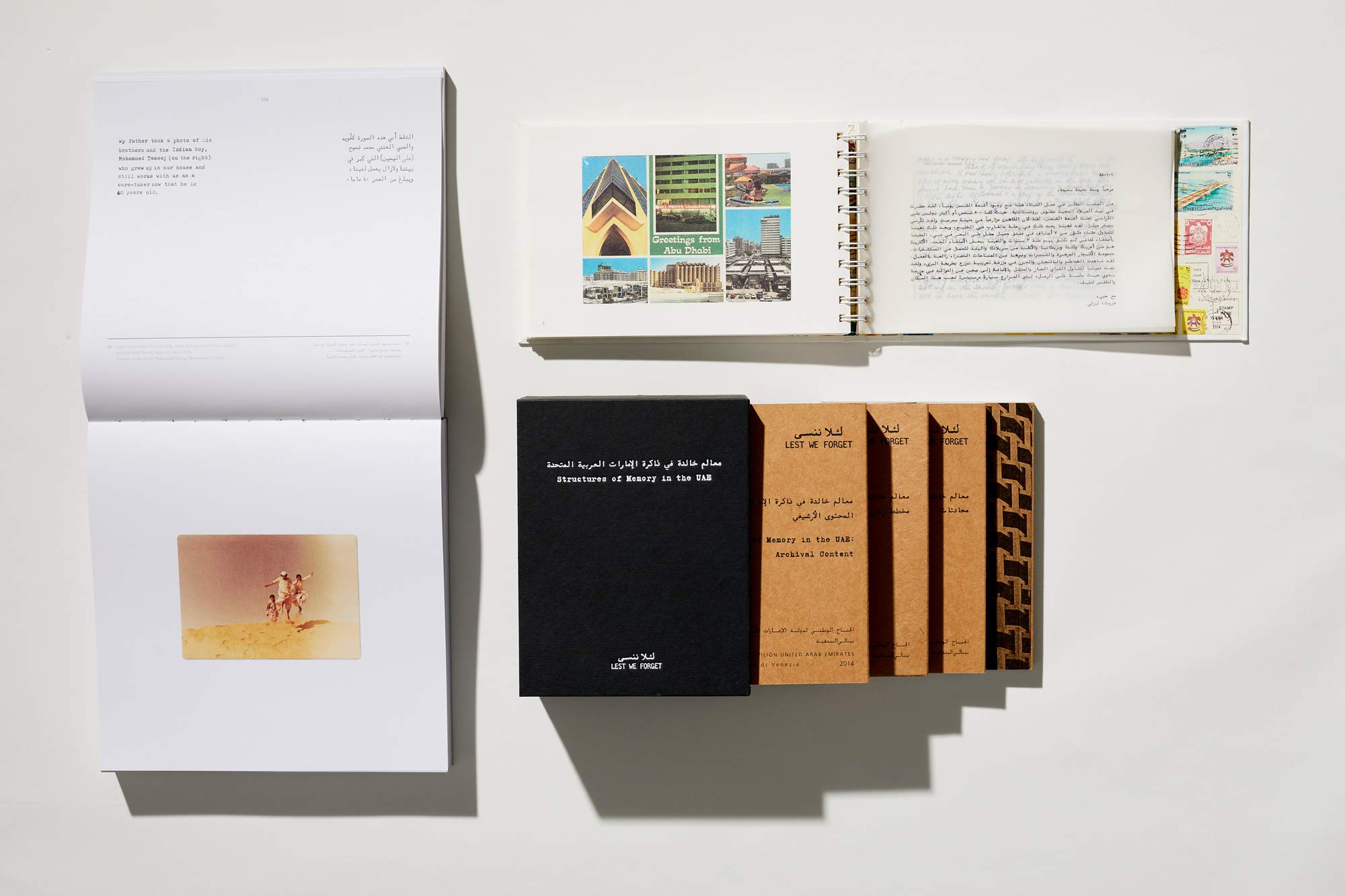

Lest We Forget

Human interest

Started in 2011 as a class project by four female friends in Abu Dhabi, Lest We Forget set out to collect oral histories from people who had experienced the uae’s seismic changes over the past half-century – the sort of souls whose accounts don’t make the history books. Today its projects have grown to include art exhibitions, books and research on various overlooked aspects of the nation’s culture. This might mean archiving memories about buildings, as in the Venice Architecture Biennale of 2014. Or perhaps the sourcing of postcards from 1980s Abu Dhabi, which might otherwise have languished in a closed drawer. Other projects include local family photos from 1950 to 1999, and catalogues of adornments from burkas and henna to bullet belts and sunglasses. The resulting archive of first-person accounts, ideas and stories casts a new light on the nation’s rapid rise.

Wael Al Awar

Swing low-rise

Fresh from winning the Golden Lion at the 2021 Venice Architecture Biennale, the co-founder of Dubai and Tokyo-based Waiwai architects tells us why the future of the UAE should be like its past: low-rise.

“I live in a low-rise area and our Dubai studio is in a low-rise area: the old town. I want to feel grounded. When I go to the top of a skyscraper I feel disconnected from the landscape; I feel disconnected from the earth. I want to connect to nature.

“I feel that the waterfront of Deira was always about nature, with the fishermen and the boats. Here along the Creek was where nature allowed people to live. This is an essential lesson to learn: you can live in certain areas only because of air-conditioning and technology but here the vernacular is all about living next to the natural. Similarly, it’s important to be able to see where you are and see the sky. It clears your mind.

“Our belief at Waiwai is that the modern architect became this godly figure who literally put other buildings in the shade. That’s not our style. Our buildings are conceived by absorbing the areas around them – the craft, culture, identity and humanity of their surroundings. And low-rise is how people want to live.”

Illustrator: Lalalimola