Domestic kitchens / Global

Come on over

We’ve dropped in on three people we admire – a journalist an editor and a chef – for a natter. They’ve also got a few tips on cooking at home and how to entertain for friends and family. The result? Barbecue chicken, G&Ts and a drumroll, please.

At home with...

Elna Nykänen Andersson

Journalist and author, Stockholm

By Jonna Dagliden Hunt

Cooking has always been a way for Elna Nykänen Andersson to find her place: from the age of eight she would make desserts to escape household chores. “Everyone was suddenly happy; they forgot I hadn’t done the dishes or cleaned my room when they could have cake,” she says with a smile. Born in Finland, she spent much of her working life in Sweden. In the latter she was monocle’s correspondent for more than a decade, as well as an editor and news presenter at public-service broadcaster SVT.

Her latest position as press officer at the Finnish embassy in Stockholm sees her drawing threads between her native and adopted countries. One of the important filters through which she looks to understand their respective cultures is their food: that’s why her recent publishing project, a cookbook called Kära Sverige (Dear Sweden, published by Cozy), is a tribute to Swedish fare. “For me, food has always been important – a way to discover my heritage,” she says. “I have strong childhood memories that are food-related. It can be a simple rhubarb soup with milk that my grandmother made or a lingonberry semolina porridge. My Swedish husband might not fully understand its greatness every time but when I meet other Finns, we can relate instantly. It goes to show how important your heritage is – you can’t get rid of it.”

Food is also a great way to unwind in the midst of a busy professional life – one that often entails public-facing events. “There have always been two areas in my life: writing and performing. When I was younger I sang in a jazz band and played a lot of music; that’s my extrovert side. Writing has been the opposite: the solitary side. In all my jobs I have combined those two,” she says, chopping mint for a burrata dish, which she proceeds to season with squeezed lemon and black pepper. “When I’m tired of the social thing I can go back to writing and thinking about ideas. It’s relaxing doing something with my hands in contrast to using my head.”

Right now home is a roomy apartment in central Stockholm. It is one of the privileges of her new job: with impressively high ceilings, original herringbone parquet floors, beautiful stucco work and an oval tower room with a grand piano (“I couldn’t imagine living anywhere without it”), it is made for entertaining. Her job includes hosting opinion-builders and journalists for dinners and cocktails. “Food has become such a big part of a country’s image. The days Finnish food wasn’t considered good or interesting are way past,” she says. “The restaurant scene in Helsinki has really improved over the past 10 years. For me, it’s important to serve Finnish dishes at my dinners as I want to show what our country has to offer.” Food also facilitates discussions between people. “These events are all about building bridges and discovering how we can co-operate. Sharing a meal is a great setting for those kinds of discussions. I naturally love hosting people; I can’t believe I get to call it a job.”

Watching Nykänen Andersson cook, it is evident that she is a natural: she turns a humble whitefish into a centrepiece by placing it on wrinkled baking paper. Finnish rye crisp with blue cheese and pear becomes the perfect dinner-party canapé when plated on a silver tray. A gin and tonic receives an elegant twist with added lingonberries and a rosemary sprig. “I’m interested in reintroducing old recipes. I update them by, for example, adding healthier ingredients,” she says. “While most children prefer toast, ours love dark Finnish rye bread, which is packed with wholegrains and has no added sugar. It’s super healthy and also a way of holding on to our Finnish roots.”

The menu

1. Kyrö rye gin and tonic with lingonberries and fresh rosemary

2. Rye crackers with blue cheese and pear

3. Burrata with mint, basil, lemon and olive oil

4. Smoked whitefish with new potatoes, roe sauce and green salad

5. Rhubarb-almond cake with lightly whipped cream

6. Coffee, liquorice and dark vegan chocolate from Goodio

At home with...

Spencer Bailey

Editor, New York

By Ed Stocker

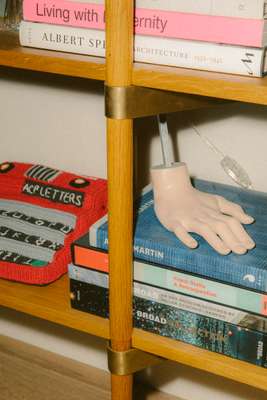

Spencer Bailey is all about the detail. An evening spent at the Brooklyn Heights apartment of book publisher Phaidon’s editor at large proves that nothing in the meticulously arranged space is there through happenstance, from design books stacked inside the Isokon Plus coffee table to a framed cover from a 1903 edition of The Ladies’ Home Journal mounted on a wall (the art director, Frank Spencer Guild, was Bailey’s great-great grandfather).

The dining table, illuminated by an Achille Castiglioni Arco lamp, provides a focal point. Here Bailey plays host to friends, often on Sunday evenings; it gives him an added incentive to get out of the house, do the week’s food shopping and visit the farmers’ market on what is traditionally the week’s laziest day. “But always small groups,” he says. “I’m not into 10-person dinners.”

Bailey has also spent plenty of time contemplating the mise en place. The white table, complete with Eames chairs, is laid with ceramics from a recent holiday to Kyoto and a central flower arrangement that Bailey plucked from a nearby florist. “I rarely get invited to my friends’ houses because most of them don’t cook,” he says. “I either host or we go out.”

Play your cards right at chez Bailey and you’ll be seated looking towards the furniture cluster and views of the “flattened landscape” out the windows, rather than at the open-plan kitchen. Not that the view is bad if you happen to end up gazing that way. Here a Zen-like Bailey is putting the finishing touches to his US-meets-Japan dinner, aided by his partner Lily Wan. There is leek-and-potato soup to start, then a carrot and pinenut salad, as well as a miso-glazed oven-baked salmon served with white rice and market-fresh wild onions (known in the US as ramps). Dessert is a shiso-flavoured ice cream that Bailey’s friend, architect and designer Stephanie Goto, had made for tonight by Manhattan ice-cream shop Morgenstern’s.

In a city famed for its enthusiastic embrace of takeaway food and restaurant culture, Bailey likes to buck the trend. Despite being at Phaidon since leaving his five-year stint as editor of design magazine Surface last year – as well as launching his own media company in May called The Slowdown – he says that he still likes to make time to cook. “It’s meditative; it allows me to slow down.”

That ethos of contemplation and taking a step back seems to run through both Bailey’s public and private life, whether it’s the methodic decoration of his apartment or the way he likes to digest media – the antithesis to the increasingly dominant click-bait culture. Yet he says that his new journalism venture is about more than simply encouraging people to take a breather. “It’s about encouraging a different way of thinking by presenting people and ideas that espouse slowness as something that’s not prescriptive,” he says.

The company was founded alongside photographer and film-maker Andrew Zuckerman and is focused on the intersection of culture, nature and perspectives on the future. The pair have so far rolled out a podcast called Time Sensitive, with plans to unfurl a Slowdown newsletter later in the year, as well as additional video content.

Despite his rapid rise through New York’s publishing echelons (he’s still only 33), Bailey has never used his knack for hosting for career gain. “It’s less about deals – meals are like catalysts for future projects.” When it comes to bringing his different worlds together, he prefers to do it outside the house, like the time all his “closest relationships” celebrated his 30th birthday at Brooklyn’s Vinegar Hill House. About 50 people took over the diminutive space, from friends to work colleagues, in what was, he says, “a non-transactional way”.

While home hosting may not be about business, that doesn’t mean there haven’t been unexpected social shoulder-brushing moments – like the time he found himself sitting opposite one of his drumming idols, Billy Martin from New York’s 1990s avant-garde group Medeski Martin & Wood. In that instance, the likes of Big Red Machine and Andrew Bird wafting out of his Bang & Olufsen speaker weren’t going to cut it. Instead, after dinner he took Martin downstairs to where he keeps a drumkit and asked him to have a go. As one might expect: “He kicked it.”

The menu

1. Leek, onion and potato soup prepared with unsalted butter, white wine and vegetable stock, garnished with chives

2. Grated carrots with toasted pinenuts and chopped parsley, with peanut oil and lemon dressing

3. Salmon fillets glazed with a miso marinade that includes mirin, saké and sugar stirred into sesame oil

4. Shiso ice cream, made to order by architect Stephanie Goto from Morgenstern’s in Manhattan

At home with...

Lennox Hastie

Chef & restaurateur, Sydney

By Clarissa Sebag-Montefiore

When Lennox Hastie decided to open Firedoor – his acclaimed restaurant – he visited no less than 121 different sites across Sydney in a process that ended up taking four years. At the time he was a consultant for Fink Group, one of Australia’s most innovative hospitality outfits and now owner of his restaurant. “It was a huge amount of pressure for me back then: there was such a big anticipation in terms of the opening,” says the UK-born chef. “Anytime I went anywhere it was written about in the press.”

On the weekday morning we meet, four years after Firedoor opened, life is considerably more relaxed. Hastie is preparing lunch at his spacious North Shore home, a 25-minute drive from the harbour bridge and bordering Garigal National Park. As the autumn sun streams through the bush-land that surrounds his garden, he adds wood to a makeshift barbecue, which crackles and spits. On top of a grate laid upon two bricks, he places a glistening, fat chicken. “You don’t actually need a lot of fire, just heat. Be patient: wait until the fire burns down, otherwise [the meat] gets engulfed in flames,” he says.

Fire is central to Hastie’s cooking. Indeed, a wood-coal fire sits at the heart of Firedoor. “That’s the engine room,” he says. “It was really important – it had to be the centre of the restaurant.” Dishes such as charred kale with garlic scapes (stalks) and Wagyu beef with smoked aubergine are cooked in the open kitchen on the flames. Wood – from Australian ironbark to apple wood – enfuses the ingredients with flavour. It’s something that Hastie swears by: he spends au$50,000 to au$60,000 (€30,000 to €37,000) on wood per year.

At home too, Hastie can’t do without a fire pit. Sometimes he cooks a whole pig or lamb in the company of his neighbours: “We light a fire early, have a breakfast of eggs and bacon around it and then put the animal on.” Sometimes it’s a giant paella, which he tends to with a glass of wine in hand. Such outdoor dining, surrounded by nature, is “part of the joy of living in the bush”.

Today Hastie is cooking his take on panzanella, created from leftover ingredients. His wife Diana, a former surgeon turned Scottish-dance instructor (really), often makes fresh bread for the family. When it goes stale it is either given to the chickens (Hastie’s four-year-old son Alex collects the eggs) or, in this case, baked into croutons.

Humming as he goes, Hastie tosses in herbs from the garden (those that have survived the kangaroos). Then there are tomatoes, grilled peppers (salvaged from Firedoor), chicken and a liberal sprinkling of salt – “Don’t be shy,” he says. The result is a salad of vivid reds and greens. Hastie, the son of an Australian company secretary and a Scottish pharmacist, grew up in Sussex, England. Aged 15, while still at school, he went to work in his first Michelin-starred restaurant. It was then that he knew for sure that he wanted to cook. “I remember my first shift: I was deranged but exhilarated.”

Later, Hastie worked for other Michelin-starred kitchens, including Le Manoir and La Gavroche. In 2006, he moved to the Basque Country in Spain to work with Victor Arguinzoniz at Etxebarri, where his love of cooking on fire grew. “It has this really wild coastline and really great seafood,” he says. “Food is so important to the Spanish. It could be a bowl of beans, for god’s sake, and they’d argue about who grows and cooks it the best.”

Moving to Sydney in 2011 – attracted by the abundance of produce, the endless sunshine and the harbour lifestyle – Hastie wanted to instil a similar obsession here. At Firedoor people often come for the steak – but then they will order cauliflower or grilled leaves on the side and “will be surprised how great that can be”.

Hastie insists that “half the battle is the ingredients”, a maxim he lives by when he cooks at home. For pasta, make sure you have good eggs and good flour. When cooking with wine, choose good wine. “The characteristics are going to have a difference on the dish.” The chicken he eats, meanwhile, is bought from a nearby farmer rather than the supermarket. “Any time you’ve got something that’s high-quality, it always makes you feel fuller and has more value nutrition.”

When Hastie drives in to the restaurant – as he does most days – he often stops to forage along the way. After our lunch, that means collecting wild juniper for his Firedoor special of raw kangaroo with charred onions. As he says: “It makes sense to use ingredients that are already there – things that are right on our doorsteps.”

The menu

Panzanella salad with one whole butterflied chicken (seasoned with garlic, lemon, rosemary, thyme and marjoram), toasted stale sourdough, tomatoes, onions, pepper, fennel, beans, kalamata olives, basil and parsley

“‘Panzanella’ creates something truly wonderful with just bread and tomatoes – and you can generally add any other ingredients, depending on your liking,” says Hastie.