Picnics / Global

Laying on a spread

Monocle’s contributing editor Alica Kirby holds forth on the power of picnics to enliven city life.

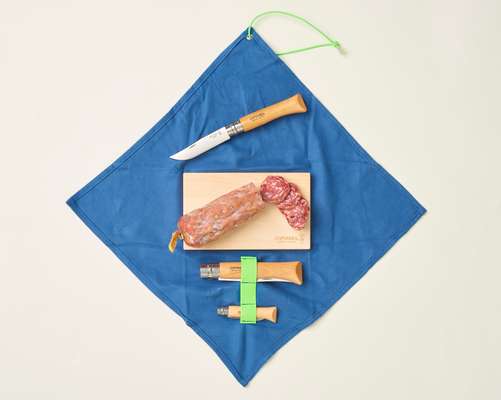

As the mercury rises, scenic spots and city parks the world over are besieged by an unusual tribe. These relentlessly optimistic (and usually hungry) souls are hell-bent on one thing: that age-old and gloriously idle pursuit of the summer picnic. Some come armed with cool-boxes, blankets and stools (to keep grass stains from their skirts) but it’s always the spontaneous and laissez faire sorts who look like they’re having more fun. This no-frills brigade is wise to the fact that the best picnics are less about culinary posturing and more about a down-to-earth experience.

It’s about a cold meal that is thrown together without formality. Sometimes even a disposable barbecue to grill your meat with, purchased not a week before the event but only when en route to locations such as Stockholm’s Skinnarvik Hill to watch the sun set over the waterfront. The allure of the picnic lies in its offer of an increasingly rare kind of freedom: being in the great outdoors with our nearest and dearest, away from the pinging, flashing demands of our laptops and out of our homes. There is something about eating while slouched on a blanket that allows us to be cavalier, even primal, with our table manners. We drink until we’re drunk and lick the sticky residue of honey-and-mustard glazed sausages from our fingers with abandon. Eating outdoors in the fresh air does something to the stomach: it rumbles with happiness. Turkish kofte, Spanish tortilla, Japanese onigiri: every nation’s staples, which might taste bland in the confines of the home, are elevated to ambrosial heights.

Being half-Japanese and half-English, my life has been defined by two very different iterations of the picnic: the pastoral English affair and the Japanese cherry-blossom-viewing hanami in spring. The English picnics that are prominent in my memory are the annual ones that took place on parents’ day at my Catholic boarding school. For months leading up to the event the nuns would pray for sunshine – a weather-manipulation method so effective that in the school’s century-old history, lore told, it had never rained on the parents’ day picnic. Said parents produced a posh mishmash, a culinary bastardisation of French, Italian and Middle Eastern fare. Green-pea hummus, globes of mozzarella in plastic tubs and quiche Lorraine were all washed down with Pol Roger or Pimm’s with lemonade.

The annual Japanese hanami picnics were more ordered affairs. Japan is a nation so punctual that even its cherry trees have been genetically altered so that they blush pink in unison across the country. The hanami is not the time or the place to ad-lib as they do in the West. To secure a spot in Tokyo’s Yoyogi Park, for example, junior employees are dispatched first thing in the morning to reserve a place amid a swathe of other blue tarpaulin sheets. The beer is never less than ice cold. The food is meticulously compact and served in gridded wooden or lacquered bento boxes. Sushi rice couched in pouches of soy-simmered tofu skin; knobbly lozenges of deep-fried chicken; croquettes smeared with fruity “bulldog” sauce; and for dessert the sakura mochi, a pounded, rose-coloured rice cake swaddled in a salted and pickled cherry-blossom leaf. The common denominator of both these types of picnic, however, is the beauty of nature, even if that means a shady lawn in an average park. And as cities grow and our homes shrink, these little parcels of available land form a meaningful link with the world around us – a notion to which city living can make us a little blind.

Two years ago this point really hit home. I was having a picnic, sitting on a towel with my then five-year-old daughter on London’s Hampstead Heath, when suddenly the sky was filled with a cotton-like snow that wafted on the breeze from a cluster of poplars. It was filmic. It was as if 1,000 angels hovered in the sky, begging for the audience that gathered together and gazed in wonder. It was then, looking down at our limp Philadelphia sandwiches and radioactively pink supermarket taramasalata, that I realised the key ingredient to a picnic, wherever and however it’s observed: nature. It has the power to turn even the simplest of picnics into the sublime. Now let’s do as the nuns do and pray that the weather holds out for long enough to enjoy it.