Rural retreat / Italy

Living off the land

Once a wreck, the refurbished Tuscan estate of Potentino is now a draw for city slickers keen to put urban life behind them and get back to the land – even if it means digging ditches for free.

Rising above the unspoilt wilderness of southern Tuscany, Castello di Potentino dominates a silent emerald valley. The taming hand of humans is visible only in a few ordered vineyards and olive groves. But a little less than two decades ago the soaring stone castle, with foundations dating back 1,000 years, was in ruins. That was until Londoner Charlotte Horton, a self-confessed former anti-Thatcherite punk, now a vintner and rural evangelist, turned the castle into a destination for aspiring and like-minded agrarians. It’s here on a hilltop in central Italy that many middle-class, white-collar city slickers have flocked in the hope of feeling closer to the land.

“This is agricultural punk,” says Horton, only slightly joking, as we arrive at Potentino on a sunny afternoon. Horton, who is sitting in a chandelier-lit foyer with her great dane, is dressed like an English country gentleman: straight blazer, tweed breeches, high riding boots. Baskets of freshly picked pears, yellow peppers, aubergines and fennel line staircases; it looks like the over-dressed halls of an English village church during a particularly bountiful harvest festival. “The farmers I found here were truly anti-authoritarian,” she says. “They hunted, they grew their own food, wine and oil. They were completely autonomous.” And this dream, achievable or not, is what seems to tempt so many here.

At just 26, Horton left London for the Tuscan countryside. She eventually stumbled upon an ancient castle bereft of windows, doors, a roof, plumbing and electricity – and decided to rebuild Potentino. She got to work on the restoration, starting by scything through weeds that had overtaken the vineyard and replanting crops. For four years she slept with bubble wrap on the window frames and under umbrellas when it rained. The castle is now a breathtaking, antique-filled residence surrounded by fields – and properly sheltered from the elements. Its land is protected by Horton’s non-profit, the Potentino Valley Project.

The renovation was a feat of her own labour and that of her brother, her new neighbours and a stream of volunteers seeking an escape who have come to define the participatory spirit in the castle.

Potentino is now, in part, a camp for urbanites who are disillusioned with the strictures of modern life – and able to afford to leave it behind for a while. So far more than 5,000 have volunteered through the World Wide Opportunities on Organic Farms programme. Zach White arrived for the grape and olive-picking season, taking several months off work: a high-stress job in international development based in London. “There’s something enormously satisfying about the physical nature of the tasks here: digging a ditch or cleaning 500 olive trees,” he says. Eileen Lee, who is on hiatus from her San Francisco-based design career, took three weeks to try farm labour instead. “I felt crushed by my work,” she says. Noah Goodman, a Yale student, is on board for several weeks with his brother. “I felt like there was more to discover,” he says. “In the city, every choice you make is damaging. In the country you can set up your own little world of how you’d like people to live.” Idealism abounds, it seems.

Most surprising of all is that none of these people want to be paid. Some are the accomplished sort who one can imagine driving a hard bargain in boardrooms back home. Here, though, they seem content to seek transcendence through agricultural tedium. Some go back to their jobs with sore knees and enough dirt under their nails to prove that they’ve tried something new. Others, suitably inspired and sincere about changing their lives, set up vineyards.

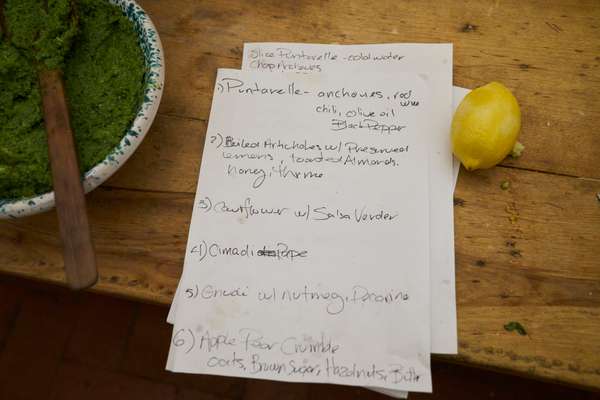

Throughout the year the castle hosts events such as writing retreats, concerts and workshops in everything from cheese-making to perfumery. When we visit, 50 food-focused idealists are on hand for Terroir: a roving Toronto-founded culinary conference that has hosted participants in Vienna, Warsaw, Berlin and now here. Throughout the week there are discussions about the nobility of natural wine, the diet of ancient Etruscans (really) and the nourishment we can gain from seaweed but often overlook. A pig is publicly slaughtered, bled and prepared into its assorted deli cuts. Many are here to see how the proverbial sausages are actually made. There are brief forays into olive harvesting, making wool by hand and foraging, some of which takes place worryingly close to the carpark. There are also massive dinners by illustrious chefs, such as Avinash Kumar of London’s River Café and Amanda Cohen of New York’s Dirt Candy, all put together with the help of a fleet of altruistic kitchen hands.

Terroir guests are bound together by a belief in a more transparent supply chain for food. Many express dismay at the food industry’s renunciation of seasonality, sustainability and flavour. There is a shared sense that we’ve got everything wrong in our mechanised modern world and, as with most cases of disenchantment, that a virtuous model existed in a rosy, long-lost past. Lots of people here express a belief that pre-industrial farming – handwrought, chemical-free, and low impact – maintained the proper equilibrium between farmers, food and land. Sadly the feelings of a small group of food folk – well enough off to be reflecting in the Tuscan hillside – are unlikely to reverse the course of industrial food production on their own. But that doesn’t mean that this change in attitude isn’t emblematic of a broader shift among a certain demographic, who are trying.

“The view has long been that cities isolate you from the vagaries of climate, storms and drought, that nature is dangerous and big companies keep danger away from you with sterile food,” says Eric Archambeau, a venture capitalist who funds technology start-ups working in sustainable agriculture. “But the reality is that we’re forced to use more potent chemical fertilisers and pesticides every year.” The survival instinct that first drove us towards the reliable, antiseptic abundance of industrial food now propels us away from it – and back towards a hands-on relationship with the natural world. But how many of us have the resilience and confidence to drop out of city life and transform a patch of land?

At Terroir, participants had surpassed the usual sanctimony; some, like Horton, turned their back on cities to try their hands at farm life. Albert Ponzo, previously an executive chef at a top-rated Toronto restaurant, relocated to a 25-hectare property of wheat, vegetables, ducks, deer and cattle. Next year he’ll launch a farm-to-table restaurant for The Royal Hotel in Picton, 200km from Toronto. “Farming is much harder than I thought,” he says after a stint in the Potentino kitchen. “But the fact that I’m sustaining my life through things my hands do makes me feel human, it makes me feel alive.”

Francesca Ruffaldi and her husband left Florence for the Tuscan countryside to launch cheese-making firm Caseificio Murceti. “I wanted to be emancipated,” says Ruffaldi, stirring milk into curds. “We decided that a different sort of freedom was possible outside the city, even if it seemed old-fashioned.” Poul Lang Nielsen, who sells produce to restaurants from HindsholmGrisen, the free-range, organic pig farm he founded in 1995, agrees that change is afoot. “Young people are copying what I’ve done: buying a farm and making it work.”

One of the standout events on the Terroir schedule was a tasting of Horton’s wine. Despite starting at 11.00, the dining room’s long wooden table was packed with dozens of eager punters. “Civilization starts with our relationship to nature,” says Horton, unfurling a chart showing the 70 additives used in commercial wine. Hers is the antithesis: its made with native yeast, minimal sulfites, no pesticides and no additives. In essence it’s similar to the wine that those canny Etruscans made here at Potentino 2,500 years ago. “The extraordinary biodiversity of Italy’s food and wine staples is at risk of being lost,” says Horton. “But we are a continuum. Everything we know about growing food and wine is based on thousands of years of accrued knowledge. If we lose that, we lose our humanness.”

Like everyone else at the table, we sip our wine appreciatively. As we drink we feel as though we’re a humble part of this historical plot twist. We might never dig a ditch or turn a plot of land into a productive field of food. But we can raise a glass of natural wine to those who have enough of the punk spirit in them to do exactly that.