Setting out our table / Global

Setting out our table

Our reporters and editors have it covered, from tasty reportage and newsy bites to some juicy opinion and toothsome takes.

Observation 1

Cooks in nooks

Why tiny kitchens are the order of the day in New York.

“We live a block away so we bring stuff,” says Melissa Burnette, who is standing inside Belle Harlem, the restaurant she owns with husband Darryl. She’s looking at a small red push cart stacked with salad bags, bottles of juice and a few cookbooks taxied from home. Having a 12-seater restaurant in Harlem, New York, isn’t without its challenges, storage being one of them. In fact, Belle Harlem measures a mere 25 sqm – and that includes the bathroom.

A diminutive space reinvents the notion of intimacy and, for the Burnettes, it means putting in some groundwork at home, growing herbs on their roof and finding nifty solutions around the fact that everything is electric, including the induction cookers. Darryl says that he loves the concept of “living tiny” because it means you’re “unfettered by shit”. But the chef admits that economics had a big part to play. Even Harlem, well above Central Park in Manhattan, hasn’t escaped rent hikes and small is simply more affordable. But it means that you have to be creative if you’re going to make it.

Over the past few years many a column inch has been dedicated to how expensive New York has become, forcing out smaller culinary players who have chosen to try their luck in smaller cities such as Atlanta or Minneapolis. The couple say that they moved to Harlem “chasing a dream” and admit it can be tough. But being small means that restaurateurs can stay nimble without having to untangle themselves from a web of partners. “We didn’t want investors,” says Darryl. “We wanted to do it ourselves.” Having 12 seats also means that it’s easier to chop and change the southern-influenced menu at short notice.

These sorts of mini kitchens don’t allow margins for error; burn that pan-fried fish and your customers will know about it pretty quickly. Being highly organised is key. Over at Mediterranean-inspired Hart’s in Brooklyn, chef Katie Jackson is pointing to the customised shelving units from the kitchen where she’s been chopping vegetables. She says prepping and marinating are two key techniques that will see her through that evening’s covers. “I’m used to small kitchens but this is particularly small.”

As city rents rise, expect these dinky diners to do the same.

More NYC mini kitchens

1. Belle Harlem: Feels like you’re eating at a kitchen counter in someone’s tiny home. Try the black sea bass and house-smoked pork tenderloin.

belleharlem.com

2. Hart’s: Co-founder Nialls Fallon says the food is shaped by the space; they can only plate five dishes at one time.

hartsbrooklyn.com

3. Piccola Cucina: Three Italian restaurants in lower Manhattan all bear the Piccola Cucina (Small Kitchen) name. Sicilian owner Philip Guardione still serves 200 covers per day in the smallest, Piccola Cucina Enoteca.

piccolacucinagroup.com

On the go: Scoops from around the globe

How the shopping trolley became Paris’s must-have multiwheel accessory.

The shopping cart has always carried sartorial baggage as well as groceries; it’s deemed suitable for the older, infirm shopper who can’t manage a tote bag. Not so in Paris. Here every one of the capital’s supermarkets is lined with wheeled chariots de course or poussettes de marché. Their owners are chic Parisians (young and old) who proudly trundle their carts along the boulevards to Sunday markets.

Here everyone, from well-heeled Left Bank types to the bobo youth of South Pigalle, has a shopping trolley. In an era of direct-to-door deliveries they are a grounded sign of being a real Parisian who frequents the markets. Retailers have issued hip incarnations of the chariots de course: Monoprix’s recent versions of colourful prints and even gold lamé flew off the shelves. French company Perigot has launched a fashion-influenced khaki model and a minimalist white paper-effect cart in sturdy Tyvek. Yet it’s the classic styles that carry the most kudos: the willow-woven basket by Lehodey has a timeless charm. Perhaps the most authentic are the simple aluminium cages on wheels – the more worn and pavement-weary the better.

Cutting edge

Portugal’s manufacturing scene may seem traditional but the nation’s focus on high-quality, low-volume products has made it a key cutlery manufacturer. Firms such as Herdmar, founded in 1911, and Cutipol, in operation since 1964, are clustered in the north in the small town of Caldas das Taipas and combine age-old techniques and ergonomics.

“Cutlery is often seen as just a basic item but we want to create an object that really helps to dress a table,” says Herdmar’s marketing manager Fernando Castro. In the early 2000s many European manufacturers went to Asia to save money – but what they saved in cash they lost in credibility. “The shift to China helped us because we moved away from low-cost unbranded products,” says Castro. “Now we work with young designers and focus on innovation.”

It’s an approach that’s paying off: Herdmar’s annual turnover is €7m and it has 120 staff. And its designs? Very incisive.

Selling bee: Dutch horticultural firm Koppert sells bumblebees in boxes. Its flagship product Natupol costs €75 a colony, including a queen, workers, eggs and some sugar water to keep them happy. Why would you buy a box of bumblebees? Well it’s not for the honey: it’s for fertilising crops. And if pollination isn’t your thing, Koppert is crawling with other suggestions. Need something to gobble up those pesky aphids? Pick up a bag of 100 ladybirds for €45.

Five steps to...

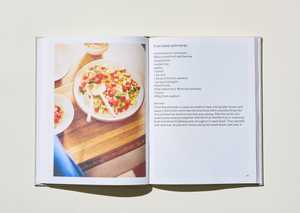

Pea, ricotta and kale fritters with roasted cherry tomatoes

Makes 8 small fritters

1. Put 250g of sweet vine-ripened cherry tomatoes onto a small baking tray, drizzle with 1 tsp of olive oil and season with sea salt and freshly ground black pepper.

2. Preheat the over to 200c. Roast for 20 minutes until softened and slightly blistering.

3. In a medium bowl, lightly crush 100g petit pois with a potato masher or fork. Break 3 large eggs into the bowl and lightly whisk, combining the peas as you go.

4. Finely shred 50g of kale and add to the eggs, along with 200g ricotta, 15g grated parmesan, the finely grated zest of ½ a lemon, 1-2 pinches of chilli flakes and a small handful of roughly chopped basil or mint. Season with sea salt and freshly ground black pepper.

5. Put a large non-stick pan over medium heat and add a drizzle of oil, swirling it to the edges. Add spoonfuls of the mix to make 8 small fritters. Press down lightly and cook for 2 minutes until golden on the underside. Carefully flip over with a fish slice and cook on the other side until golden and cooked through. Serve the fritters topped with the cherry tomatoes and a chilli sauce of your choice.

Hook, line and sinker

Snøhetta’s Muttrah fish market in Oman toes the line between old customs and new buildings swimmingly. The digs are an ambitious undertaking, seamlessly connecting the sea-port town with nearby mountains and the bustling waterfront. The building’s shapely form and ephemeral aluminium fins mirror those of the creatures that are traded within its halls; the market is proof that architects can bring fresh thinking to spaces that have existed for centuries.

Meanwhile, the same architecture firm’s underwater restaurant in Norway – a grandiose slab of concrete half sunk into the North Sea – focuses diners’ attention on the rich water from which their dishes are plucked. Some architect are preoccupied with reviving old buildings and market projects but new builds can be part of the recipe for understanding our edibles too.

What bottled water did next

Today’s hydration-fixated consumers are hooked on bottled water – one million bottles are bought worldwide every minute. It’s a health kick but one that’s contributing to a looming environmental crisis.

Luckily several companies have a satisfying solution – though one suspects the profits of a market expected to be worth €193bn by 2025 are part of the motivation too. Michigan-based 1 Boxed Water carries its cargo in fully recyclable cartons – 74 per cent of the product is made using paper from certified, sustainably managed forests. 2 Just Water (founded by actor Will Smith’s son) is also packaged in recyclable containers and claims to be driven by sustainability, not profit. Meanwhile futuristic sustainable-packaging company 3 Notpla in London is making a splash on the start-up scene. Its edible, drinkable and compostable water bubbles are made from seaweed – just pop one in your mouth and go. When the world seems to be drowning in plastic, it makes sense to go with the (new) flow.

At a pinch: Those seeking a last-minute holiday trinket could do worse than the offering at Halifax International Airport – live Nova Scotia lobsters. You can buy the crustaceans (packed with frozen peas rather than ice to meet aviation security requirements) from a Clearwater fishmonger in the departures hall, then simply take your boxed lobster through the scanners and on to the departure gate. It’s one way to ensure that you have the snappiest carry-on.

Four steps to...

Chicken with ginger, lime and miso

Serves 4

1. Place 8 large chicken thighs into a large non-stick pan, skin-side down, and cook over low to medium heat for 10 to 12 minutes until nicely golden.

2. Meanwhile preheat the oven to 160C. Chop 4 spring onions into 3cm chunks and scatter over the base of an ovenproof dish. Place the chicken on top. You want the pieces to fit quite snuggly.

3. For the marinade, mix 2 tbsps of mirin, 2 tbsps of honey, 4 tbsps of white miso, 1 tbsp of tamari, the juice and zest of 1 lime, a 2cm piece of ginger (chopped), 2 chunky garlic cloves (chopped) and 2 sliced green chillies (optional). Season.

4. Pour over, around and under the chicken. Cook for 40-50 minutes until golden, slightly sticky and cooked through. Serve with chopped coriander.

Observation 2

Back on track

An historic Portuguese train that once hosted royalty (and despots) now whisks curious diners through the Douro Valley on a journey of culinary discovery.

At 11.00 on Friday and Saturday mornings in autumn, trainspotters gather on platform five at Porto’s São Bento train station. They are here to board a Prussian-blue train on a 10-hour trip up the Douro Valley. The journey includes lunch, plenty of Portuguese wine and the pleasure of riding a private train once used by heads of state such as dictator António de Oliveira Salazar.

The interior, some parts of which date from 1890, is beautiful. From a time before the domination of plastic, the train features polished wooden wall panels, leather door handles, green velvet seats and brass window pulls, buffed to a lustrous shine. But while the stock may be historical, the way in which the Presidential Train venture approaches tourism offers a glimpse of a new Portugal: traditionally known (or, at least, overlooked) for its affordable and relaxed hospitality, hearty food and family-run restaurants, the country is rapidly becoming an upmarket and fine-dining destination attracting visitors from across Europe, the US, China and even Australia.

On boarding the train, guests are seated in their carriages and served Portuguese sparkling wine while a soundtrack compiled by Porto’s Casa da Musica plays in the background. In the dining cars, flower-filled vases adorn white-linen covered tables and young waiting staff polish wine glasses. Each week a different chef takes the helm and on this journey, the man in charge is Vincent Farges, who can usually be found decorating plates with colourful slicks of sauce and setting globules of emulsion on top of delicate portions at Lisbon’s fine-dining Epur restaurant.

The train’s kitchen resides in the former baggage compartment and as the train departs, staff are already at work. In the former mail room, pigeon holes hold loaves of fresh bread, shipped from a specialist baker in Lisbon that morning. A waiter saws slices, moving with the rhythm of the train, crumbs falling like snowflakes. In the new kitchen, complete with an industrial-sized hob on which large pots of stock are bubbling, Farges and his assistants are busy with the first course, delicately placing grapes and prawns on plates. As the train picks up speed, the noise is deafening and the team have to shout to be heard. Then the train heaves to a sudden stop.

“It’s a bit rock and roll,” says Farges, laughing. “But it’s a great experience for a chef. You can’t be too delicate when you cook in these conditions.”

A five-course meal is served as the train trundles along and on the return journey a bar opens in the carriage that was formerly Salazar’s private suite. At one end, a waiter mixes gin and tonic while Jorge Santos Silva, a music teacher turned part-time entertainer, plays easy-listening favourites on the piano. As night falls, the background noise of the train is joined by the hum of voices speaking in a variety of languages and the sounds of a Coldplay song are followed by something by Elton John. It’s hard to know whether to toast the revolution or mourn the passing of more traditional times.

Glass half empty: Ordering a drink used to be simple: “Lager, please.” Then along came craft beer to complicate matters. But a sobering report has found that the number of new craft breweries entering the UK market decreased sharply last year, while numerous independents are being bought up by the likes of Asahi and Heineken. There’s hope, then, for a future where I go to the bar and my order isn’t met by a tutting barkeep and sniggering patrons. Lager, please.

Market confidence

by James Chambers

Hong Kong’s oldest food market can be found among the skyscrapers and shops of Central. Thousands of people pass through it every day, oblivious to the boarded-up building’s former glory. Central Market closed its doors in 2003 and is due to reopen in the next few years.

The Hong Kong government should be applauded for preserving the city’s prewar architecture: the four-storey cement structure was built in the 1930s, replacing a Victorian brick building. However, heritage is not purely architectural. When the market reopens, the newly air-conditioned shops are likely to be slick and sanitised, bearing scant resemblance to the messy stalls of old. A refresh is long overdue but throwing out the past wholesale would be a huge mistake.

Fresh-food markets are an intrinsic part of Hong Kong’s culture. Most if not all neighbourhoods have a so-called “wet market” where stalls operate every day. Shoppers elbow past each other on crowded streets as radios blare out Cantonese talk shows; fish lie on mounds of ice and old ladies hawk pak choi and gai lan. Meanwhile butchers sell nose-to-tail produce: pig snouts hang on hooks alongside oxtails and bull testicles. It’s a bloody mess and workers wear wellies with good reason.

Wet markets can seem like a hangover from a bygone era but they might also point to the future of food retail. The supermarket experience, from plastic packaging to the mountains of waste that come from stockpiling food, is becoming increasingly unpalatable to today’s eco-conscious city dweller. Consumers want to buy fresh, unpacked food and many Asian cities still have these markets in abundance. However, rising household incomes are threatening their existence. Hanoi in Vietnam is an example of a city where shiny supermarkets are grabbing a larger share of the family food budget. But Hong Kong is an interesting case study because food markets have largely survived rapid development, although their future is far from certain. Stall holders are ageing and customers tend to be Filipina housemaids sent to the market with a grocery list.

The government should help these businesses appeal to a younger clientele by investing in modern signage and mobile payments; better cuts of meat and a little less mess wouldn’t go amiss either. Money talks in Hong Kong so the Central Market should be used, once again, to blaze a trail for modern food retail. A few years from now, thousands of bankers and lawyers could be stopping by on their way home to fill their reusable bags with fresh produce. Wet markets across the city – and the region – would quickly take note.

Four steps to...

Red cabbage, beet, carrot and apple sauerkraut

Makes about 1kg

1. Scrub 200g of carrot and 200g of beetroot. Coarsely grate the carrot, beetroot and 3 cored small green apples. Shred 1 small red cabbage. Place into a bowl and add 3 heaped tsps of sea salt, 1 tsp of coriander seeds, ½ tsp of fennel seeds and 8 juniper berries, toasted in a dry pan and lightly crushed.

2. Stir well and leave for 30 minutes, then massage with clean hands for 1-2 minutes to get the vegetables macerating.

3. Pack the veg into a 1 litre kilner jar. Use a rolling pin or wooden spoon to push the contents down as you go (this will create some juice at the top). Ensure that the vegetables are fully submerged and leave a 2cm gap at the top. Place a small round of greaseproof paper and an object heavy enough to weigh it down on top. Tightly close the lid.

4. Every couple of days, loosen the lid to allow any gas out and at the same time check that the vegetables are still submerged. It will be ready in 5-7 days but you can leave it for up to 3 weeks for a stronger ferment.

Unhealthy obsession: Japanese food is famously healthy but queues are forming for imported junk food. Tokyo teens are in thrall to Korean hatogu: molten mozzarella on cubes of deep-fried potato, slathered in ketchup and mustard then rolled in sugar. Keep it up and Japan’s low obesity rates could see unprecedented gains.

Show me the door: Do judge a restaurant by its entrance

An inviting entryway can make the difference between feast or famine.

A restaurant’s success can hinge on first impressions but developers are overlooking the subtle message transmitted by entrances when it comes to new openings. Some girthy doors, five inches thick, seem better suited to keeping guests out than welcoming them in; ditto the dark-dressed doormen who look like they double as security.

The best entryways should seduce you and show enough to pique your interest. Entrances nonchalantly tucked down back alleys or flanked by hedgerows feign privacy but create presence and beg investigation. Equally an air of mystery or intrigue gleaned from behind a curtain, through a stained-glass window or around a charmingly ramshackle door prepares your palate better than an aperitif.

And remember, a good door is as good an omen as clean windows: if someone’s thought of keeping them buff and polished there’s a good chance they clean the oven and the fridge too. Developers favouring samey fit-outs should think again: an over–styled door looks more like a cover-up than a reason to explore further.

Observation 3

Fit for a (Norwegian) king

The chef at Oslo’s Royal Palace on what it takes to feed a very busy household.

With the radio tuned to a heavy-metal station, Nicolai Lundsgaard is filleting a Norwegian haddock to the accompaniment of Metallica’s 1988 single “Eye of the Beholder”. Only the porcelain and silverware bearing various royal monograms hint at the traditions and expectations linked to this kitchen in the basement of the royal palace in Oslo.

A few days earlier, under sparkling chandeliers in the palace’s great dining hall a few floors above, some 220 guests were treated to Lundsgaard’s culinary creations during the annual royal gala dinner for members of the Norwegian parliament. “It’s all in a day’s work,” says the 44-year-old Dane who moved to Norway 23 years ago. In 2013 he landed the top job as kitchen director for King Harald V and Queen Sonja. “We are responsible for everyday food for the royals, receptions with finger food, afternoon tea, state visits, dinners for the government and parliament,” he says. “Oh and for the daily running of the canteen, which serves about 150 people on the royal court’s staff,” he adds, modestly.

While Lundsgaard respects the conventions of a royal gala dinner, he has found this job surprisingly liberating: “Things aren’t regimented at all here.” The chef and his team of nine are largely free to create their own menus but always try to source ingredients locally. “We have our own nursery and Bygdøy [the royal farm a few kilometres from the palace] also produces vegetables.”

State visits are a chance to showcase all things Norwegian and the food is a calculated part of the soft-power pull. Lundsgaard sees it and how it is presented as an important part of the diplomatic exercise. “More often than not we serve fish and shellfish. I think Norway has some of the best shellfish in the world.”

Part of the job is travelling to residences around the country, including a mountain cabin where cooking is done on a wood stove. “That was new: getting up early to light the fire,” says Lundsgaard. “Making a soufflé there for the first time was a challenge. I’d stay hunched over the oven for the duration to make sure nothing went wrong.” At the time of writing Lundsgaard has yet to serve a fallen soufflé.

The CV

1997 Completed apprenticeship at Restaurant Varna, Aarhus, Denmark

2004 Sous-chef at Restaurant Tango, Stavanger, Norway

2005 Chef de cuisine at Colonialen, Bergen

2008 Member of Norwegian barbecue team

2009 Chef at Bagatelle, Oslo

2013 Kitchen director at the Royal Palace, Oslo

2017 Mentor for Norway’s team at Bocuse d’Or

observation 4

Cold calling

After Newfoundland’s fishing industry floundered, one man found a cool new way to keep his head above water. But that’s just the tip of the iceberg.

Ed Kean is a burly 60-year-old former fisherman with a thick Newfoundland accent. “A thousand tonnes of ice is a lot of water when it’s melted – but it’s not much off a 100,000 tonne iceberg. There’s still a lot left,” he says. Newfoundland was once home to one of the globe’s most fertile fishing grounds until the cod-fishing industry collapsed. In the 1970s Kean harvested chunks of iceberg to keep his catch cool and, when the industry waned in the 1990s, he turned that expertise into a new job: Newfoundland’s first iceberg cowboy. His horse? A steel-hulled tugboat that tows a 60-metre barge and a backhoe.

From late May, Kean and his team live on the boat, working 18-hour days until late July when every iceberg in the area has melted. They’re in search of one of the 800 larger specimens, which weigh from 100,000 to 200,000 tonnes and have cleaved off Greenland’s ice shelf to make their way south to Newfoundland’s eastern coast, known as Iceberg Alley.

It’s here that Kean finds his targets. Key to his safety is knowing that 90 per cent of an iceberg is submerged: hidden ice can puncture a ship’s hull while falling chunks can flip a boat. “You’ve got to know which icebergs to pick,” he says. Kean lassoes an iceberg and a winch pulls the crew alongside. The backhoe scrapes one-tonne blocks into the water before they’re hauled aboard the barge, crushed and stored in tanks.

Iceberg water is among the purest in the world having frozen nearly 20,000 years ago, long before the Industrial Revolution. The water has spawned a lucrative industry and is used in vodka, beer, cider, wine and even perfume. Kean harvests one million litres of iceberg water annually and his biggest client is Newfoundland-based Iceberg Vodka, founded in 1995. “The idea was that using the purest water source in the world would translate into the smoothest vodka in the world,” says COO Steven Ciccolini, noting all vodkas are 60 per cent water.

Today Kean cuts a lonely figure but he knows there are opportunities here. “The vodka is very good. The beer is good too. But we forgot about what the biggest seller of all might be,” he says, explaining that he’s launching his own brand. “Pure, 100 per cent iceberg water.”

Cold as ice

Kean sells 80 per cent of the ice he collects to Iceberg Vodka. The price they pay is asecret but it’s enough to have tempted thieves to break into his warehouse to steal 30,000 litres of it.

Nuts about rayu

by Andrew Tuck

Are you on the sauce? I’ve been through phases – mustard one month, a nice tomato relish the next – but sometimes the habit takes hold and you find yourself planning meals just so you can have the damned sauce of the moment. You wake up thinking about the satisfying pop of the jar opening, of the spoon diving in.

This is the fate that awaits anyone who buys a jar of peanut rayu from the White Mausu company. Apart from the nuts it’s got chilli and sesame; it’s hot but not too hot; it’s both crunchy and oily; it’s a bit Chinese, a dash Japanese and a splash Korean; and it’s addictive. And it’s made in Dublin by a company of three people.

Company founder Katie Sanderson and partner Jasper O’Conner started selling their rayu recipe at the Dublin Flea Market in 2018 and it was in that fair city that a colleague bought some jars. One came my way – and the rest is a tale of drool. It’s good on eggs, salads, fish, eaten direct from the jar… I recently placed an order for six jars (gone in a month). My colleague placed a bigger order and handed them out. The future looks troubling – will there be any other sauce in my life? The peanut rayu is now known as “that crack sauce” at Midori House. Give it a try.

five steps to...

Prawns with orzo, smoked paprika and toasted almonds

Serves 4

1. Heat 1 tbsp of olive oil in a large sauté pan (or paella pan if you have one). Add 12 large shell-on prawns and brown them for 1-2 minutes on each side. Remove them from the pan and put them to one side, on a plate.

2. Add another tbsp of olive oil to the pan and sauté 1 banana shallot and 1 red pepper, both diced up small. After 2 minutes add 4 chopped cloves of garlic, 1 tsp of crushed fennel seeds and sauté for 1-2 minutes until the garlic is lightly golden.

3. Add 150ml of dry sherry or white wine, bring it to a bubble to reduce, then add a 400g can of plum tomatoes, breaking up the tomatoes with the back of a spoon. Pour in 200ml of chicken or fish stock. Add 1 tsp of sweet smoked paprika and bring to the boil.

4. Add 250g of orzo pasta and season generously with sea salt and freshly ground black pepper. Give everything a good stir then cover and simmer very gently for 15 minutes. Stir a couple of times so that the orzo doesn’t stick.

5. Spread the prawns over the pan, add 100g of baby spinach, cover again and cook for 3-4 minutes. Remove the lid, stir everything together and check that the pasta is cooked through. It should be nice and saucy – if it’s not, stir in 100ml of boiling stock to loosen. Serve in the pan with a handful of chopped parsley, 50g of chopped salted Marcona almonds and the juice of ½ a lemon squeezed on top. Delicious with chopped chilli.

Lying tea leaves: The popularity of Japanese food around the world means that the nation’s green tea (including matcha) exports have increased almost fivefold since 2008. But things are different in Japan, where fewer people bother to brew their own at home and more people are consuming green tea on the go from plastic bottles. The shift in how Japanese people enjoy the national brew (towards quicker and cheaper alternatives) is almost the opposite to the journey taken by coffee. The famed Japanese tea ceremony might be an entrenched part of the culture here but the ritual of waiting for a drip coffee is a better emblem of eating and drinking in Tokyo today.

(M)Arket value

Swedish retailer H&M’s fast fashion might not be for everyone but its Scandi-basics sibling Arket is making a grab for a more lifestyle-conscious consumer. Its cookbook – a linen-bound and artfully illustrated jaunt through chef Martin Berg’s seasonal dishes – is pretty proof. What’s more (and probably more infuriating for food publishers), Arket’s effort is plain nicer than most cookbooks on the market. It’s subtly styled, offers 25 or so fuss-free Nordic dishes and cleverly nudges the notion of buying in season to its fashion-forward food followers. Make ours a rye sandwich and a rollneck.