Culture / Japan

The art of eating alone

Recommendations are vital in the restaurant world but why are hundreds of thousands of Japanese poring over the culinary musings of a fictional salesman? We meet the Solitary Gourmet.

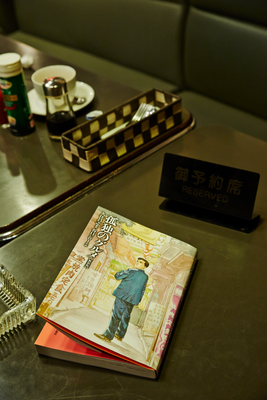

In Japan hundreds of thousands of people follow the culinary life of Goro Inogashira – and everyone likes him. But this isn’t Instagram. Inogashira has no social-media account; he’s not even a real person. He is the lone character in Kodoku no Gurume (Solitary Gourmet), a popular manga comic originally released in the 1990s, which is now a hit TV show.

The story – so much as there is one – revolves around the food that the protagonist eats at unremarkable restaurants between meetings on business trips. Inogashira is in his late thirties or early forties (the comic doesn’t specify) and runs his own modest imports business in Tokyo. The food he eats ranges from a ¥130 (€1) plate at a sushi restaurant to a bento box on the Shinkansen. Occasionally Inogashira tucks in to a guilt-inducing assortment of goodies from a convenience store at his desk at midnight. Just like the nation he traverses, Inogashira is in awe of food. He eats alone but he is not really lonely. A lot of the conversations that punctuate the story take place in his mind: he talks to himself about where to eat, what to order and the people he watches going about their business while he waits for his food. Everything from his hair to his suits – and, of course, his culinary tastes – is refreshingly unpretentious; he’s a nobody and an everyman.

The manga strip that gave life to Inogashira was an oddity, a curiosity that slowly but surely found a passionate audience. In 2012 the comic was turned into a TV drama series; now in its seventh season, it is available on Netflix and Amazon Prime. The comic has been translated into 10 languages, including French, Italian, Spanish, Portuguese, Chinese and Polish but not – as yet – English.

We meet author Masayuki Kusumi, 60, at Kayashima, a restaurant in Tokyo’s Kichijoji neighbourhood that serves yoshoku (western-style Japanese comfort food). “I was in my thirties; it was ages ago,” he says, explaining where the idea for the solitary-diner series. came from “Back then there was a bubble in the economy and it was the first gourmet boom. There were many new, expensive and fancy restaurants about.”

An editor at Fusosha, a publishing company in Tokyo, paired the author with manga artist Jiro Taniguchi and asked them to create something that would challenge the air of pretension that was becoming increasingly prevalent in Japanese life. At first the manga series, which was tucked inside a monthly magazine, wasn’t a big success. It lost its regular spot after a few years and the follow-up paperback edition was discontinued after its third print run. The reception improved when the series was released as a pocket-sized paperback. “It shouldn’t be easy to read because it’s so compact,” says Kusumi. “But sales started picking up.” Shortly after the change of format, a reprint was being ordered every six months. Today fans make pilgrimages to the restaurants that Inogashira visits. “I didn’t even dream about it,” he says when asked about the comic’s success.

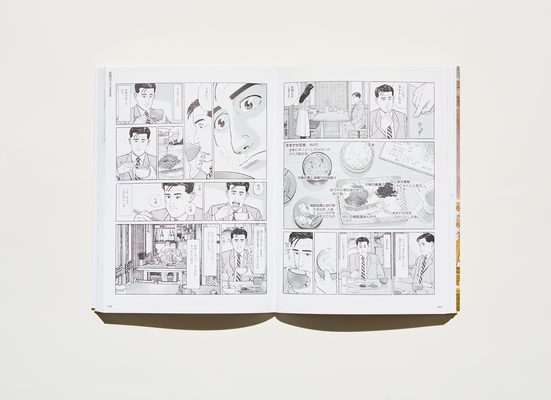

Kusumi credits much of Kodoku no Gurume’s appeal to the late Taniguchi. “Taniguchi drew my uneventful drama with meticulous touches and in microscopic detail,” says Kusumi. Modest, perhaps, but he is right to acknowledge the story’s distinct lack of action: other than Inogashira quietly finishing a dish or two in each eight-page instalment, little happens. But perhaps it’s this mundanity that makes the stories so easy to relate to. “Look at this panel,” says Kusumi, pointing at a dining scene in the pages of a paperback. “It must have taken Taniguchi a day to finish this single frame. It’s teinei [attention to detail]: that’s why people read and watch again and again. Today no TV show devotes an hour to quietly focus on one, small theme,” he says. “You have to move on fast from one thing to another and then throw commercials in.”

The TV adaptation has changed Kusumi’s life but not his process. He still explores cities on foot, seeking the setting for his protagonist’s next meal. From scouting to shooting, the production crew for the series will visit a venue at least 10 times. In one scene in a show from the sixth season, Inogashira barely utters a word. “One ‘hmm’ was enough because we have created such a vivid world,” says Kusumi. The audience is also fond of Kusumi’s relaxed attitude towards food; he’s not a snob. His protagonist avoids one thing at all costs: judgment. “I don’t like to judge,” says Kusumi. “Giving a star-rating is a bit arrogant.” Instead Inogashira adopts two practices that the author feels are often neglected: observation and contemplation.

The world that Inogashira inhabits is realistic (though it is rooted in the 1990s) but, when compared with today’s hubbub, it feels like a parallel universe. Inogashira doesn’t have a smartphone; he never uses Google Maps or reads a review on Tripadvisor. Instead he strolls along the streets pondering what he wants to eat before diving into a restaurant by following his own instinct or relying on a memory. He sits down, studies the menu and scans the restaurant in search of human drama. “I see people standing right in front of a restaurant checking their phone to see how others have rated a place they’ve never been to,” says Kusumi. “If you don’t think and decide by yourself, you cannot train your instinct.”

And the author believes that this modern convenience is having an adverse affect on restaurants too. “Imagine you’re a chef and a stranger reviews your restaurant by eating just one dish,” he says. “I couldn’t bear it. That’s the rudest thing in today’s socially networked age.” He argues that, if customers can share their thoughts on a meal anonymously on the internet, chefs should be able to judge their customers too. Where do we sign up?

Kusumi’s take on society – particularly the delight he takes from everyday experiences, even if they are mundane – is enlightening. It makes for surprisingly captivating watching and reading. So what happens when you switch off your phone and follow your gut feeling, just as Inogashira does? “Well it’s trial and error,” says Kusumi, with the smile of a writer who knows exactly what his character would say. “You make a lot of mistakes but eventually you’ll come to know what you like – regardless of what others might think.”