People and places / Global

Ahead of the pack

From publishers to soap-makers, royals to the church, we present the front-runners who will be powering the world in 2016 and beyond.

1

Driving force

Traditional taxi firms can survive and thrive – but first stop complaining.

Taxis are in trouble. Like the airline industry before it, the trade is losing ground to convenient, low-cost competitors plying their trade through backlit screens. What’s worse is that traditional taxi firms are standing by feeling sorry for themselves as these new cheaper app-powered options purr off with the punters. The coming years will be telling for the future of four-wheeled transport; however, there’s much that could be fixed in the battle of the pick-ups.

Traditional taxis in the likes of Toronto, London and Hong Kong lack in comfort, have drivers who seem unaware that there’s a generation who pay for everything by card and, worse, engage you in conversations that too swiftly lead to suspect political opinions. The shakedown may prove brutal but if taken as a wake-up call, metered taxi drivers may yet stay at the front of the rank.

Remember, airline carriers were similarly dumbstruck when budget options began siphoning off customers who were seduced by low-fare flights, with which the established airlines couldn’t – or refused to – compete. The saving grace for many of the far-sighted carriers was not engaging with the race-to-the-bottom price war. Instead, the cannier ones redoubled their efforts to show that travel with their airline still had value. They knew there was room in the market for a premium option and that people would pay for it. Japan’s Nihon Kotsu is a flag-bearer for fine service. With a fleet of 7,000 cars, the firm has held off the advances of online competitors by keeping its fleet smart and drivers dedicated (think white gloves and a refusal to let passengers open the door for themselves).

The only way back for the old-school cab is to offer something that their adversaries don’t: deep knowledge, flexibility and a kindlier service. Here’s how.

Get in the mood. In many cities cabs make money from carrying ads. But how much cooler to team up with artists during your city’s key art fair or designers during fashion week? Jumping in an Anish Kapoor-adorned taxi would be good and how about asking five architects to fix the interiors during design week?

Listen up. Let people play their own music through your sound system via a simple docking unit. Drivers could pop a cap on the volume and have a separate control if it’s not to their taste. Make the journey fun again.

Cash out. Make it simple to pay by card; who wants to have to find an atm before hailing a cab? Plus: once a year donate a percentage of takings to a charity to show you are part of the city’s fabric.

Put a cap on it. standardised fares to airports and stations would make a taxi a more viable option for longer journeys. Getting to an airport in comfort and privacy is all the more alluring if you’re sure you won’t have to drop €100 for the privilege.

Up customer service. Ultimately, cabs have come to see themselves as indispensable but competition has imperiled this and a service-minded attitude adjustment is well overdue. First, they should get off the hands-free phone call to their mum/wife/doctor. It’s rude.

Sell harder. Why don’t cabs have mini coolers to sell you simple refreshments on the go, as well as packets of mints, tissues and perhaps an ice lolly in the summer? What about offering city maps or guidebooks?

Clean up. Have a window that opens and be proud to ply your trade in a clean car. Carry a fragrance to get rid of the stink from sweaty customers. A uniform jacket would also help with brand building and keeping drivers smart.

Be accountable. Leave something in a cab and that’s the end of it. Knowing a driver’s name and number makes the experience more personal and contact much easier should you abandon your keys on the backseat. If their details were on every taxi receipt you could track down a lost item instantly.

Mind your manners. Taxi drivers are often a visitor’s first experience of a city so they should embrace it. How about offering to help with luggage? What about learning a few phrases in Spanish, German and Italian?

Best practice. Taxi drivers should be the best and most courteous drivers on the road whether they have passengers or not. No more veering towards cyclists or screaming out the window at slow pedestrians.

2- Taking flight

With its leading airlines and feathery food scene, no wonder Iceland's on the rise.

There are more than a few reasons why we’ve got our eyes on Iceland for the year ahead. The Atlantic outpost has long held an eerie allure thanks to its mysterious isolation, treeless landscape, geothermal hotspots and windswept beauty. It’s the land of the northern lights, lagoons and steaming geysers (not to be confused with the steaming geezers: inebriated Norseman propping up Reykjavík’s bars with beer-soaked beards and Brennivín by the bottle-load).

The island expects to bolster its tourist numbers from 1.1 million in 2015 to 1.5 million in 2016. Not bad for a nation of 330,000 souls. Part of the reason for this success is the persistence of its airline carriers. Wow, the name of its budget option (“leisure” in North American speak), has forged routes from Montréal to Dublin and Boston to Baltimore. Meanwhile, the regal blue-and-yellow livery of Icelandair can now be seen from Toronto to Chicago and Aberdeen; it’s also been upping its London services.

Iceland’s geographical aloofness is fast becoming its strength in the stopover market and an increasingly intriguing dogfight for flights between Europe and North America. But what does this nascent-hub status mean for brand Iceland abroad? Visitors will likely be tempted to enjoy the nation’s charms en route between popular destinations and that means settling down at the dinner table to enjoy some of the storied country’s unique food.

The Grillmarkaourinn restaurant is a spacious, well-appointed option in central Reykjavík. Lively fair-haired Icelanders fawn over the visitors that peruse its excellent but curious menu. A quick glance yields a few eyebrow-raising specialities from whale to puffin and shark; your faithful reporter drew a definitive line under the latter. Icelanders have doggedly adhered to the diet enjoyed by the settlers that first graced the Nordic nation’s shores, having hopped off longboats leaving Norway eight centuries ago. For the squeamish there’s also fresh seafood galore, which the wise enjoy with lashings of lava salt.

It’s a whimsical culinary collection of expedient eats that have long been abundant here. What’s more, there’s something about the traditional and locally sourced nature of the offerings that chimes with a wider trend in the food world. Western menus have found themselves favouring indigenous produce and as provenance reigns and purveyors seek new ways to guarantee a nose-to-tail dining experience, Iceland is uniquely placed to service open-minded eaters with hitherto untried treats. Puffin burger anyone? “Aren’t they just the pesky pigeons of the Arctic?” you’ll find yourself reasoning with your dinner companions before plumping for the platter (full disclosure: puffin is smokey, duck-like and pretty agreeable to eat).

Something about Iceland’s isolation has given its people a profound sense of nationhood and unity when it comes to eating. Despite being under Danish and Norwegian control from the 12th century until the end of the Second World War, these hardy islanders still profoundly respect the nature of their homeland. And eating in this way is an attractive prospect. Unlike its Nordic neighbours, Iceland’s relative seclusion means that its mother tongue is also almost indiscernible from that of the Vikings who first landed here, many of whom fled the taxes imposed on them by greedy European kings.

A recent taxi drive in the city exposed my driver as a lifelong believer in the existence of elves (good spirits) and trolls (the baddies). It was a charming – if eccentric and anecdotal – reminder of how undisturbed Iceland’s culture and lore is thanks to its remoteness. Although the wise are already questioning the creaky airport infrastructure – the international hub Keflavík 40km from the capital Reykjavík needs a drastic rethink – whether it’s prepared or not Iceland is landing an enviable haul of new visitors hungry to taste what the country has to offer. Something about its idiosyncratic, enigmatic allure makes me think that the Icelandic saga – in tourist terms anyhow – is just beginning. While I can’t see shark or minke whale making the journey onto menus in London or Los Angeles, pushing puffin may yet prove a soft-power pull for Iceland.

Notes: Iceland's animal menu

- Minke whale: Iceland resumed commercial whaling in 2006.

- Catfish: The dried variety served at Finnbogi in Ísafjörour is best.

- Reindeer: Ideally served as steak from Elvar in Reykjalín.

- Puffin: Try the burgers at Grillmarkaourinn, Reykjavík.

- Shark: Hákarl (as it's known) is Iceland's national dish – something of an acquired taste.

3- Scrubs up well

The Syrian city whose soap scene has slipped across the border while its country is at war.

Aleppo was once Syria’s most populous city, known for its ancient citadel and in particular its soap: a product famous for its quality since Queen Zenobia of the Palmyrene empire enjoyed its antibacterial and moisturising properties. Made from three ingredients – olive oil, laurel oil and lye – Savon d’Alep is still prized from Marseilles to Beirut.

In many ways it came to define the city: a visit to Halab, as Aleppo is known in Arabic, would not be complete without buying a few bars, says Fuad Issa, an Aleppo-born soap-lover who now lives in Washington. “There was one factory, owned by the Fansa family in the southern part of the city, where you could smell the soap being made from 200 metres away. It was a beautiful smell; not flowery, more like something from a plant.”

After nearly five years of fighting, Aleppo – one of the oldest continuously inhabited cities in the world – has been reduced to a divided ruin and its ancient soap industry ravaged by war. “Before the war, Noble Soap was a well-established company producing different items from olive oil: Aleppo soap, of course, but also shampoo and shaving cream,” says founder Nabil Andoura, whose company once exported to Japan, Europe and the US. “We had one factory, two warehouses and headquarters in Damascus.”

That all changed when the violence intensified in the city. “The factory in the countryside just outside Aleppo was looted twice,” says Andoura. “They stole the equipment, the soap, the raw materials, the oil – everything. Then the building was destroyed completely by air strikes in 2013. We know nothing about what’s left there: we can’t reach the area any more.”

After a four-year hiatus, Andoura has established a skeleton operation across Syria’s border in Hatay, Turkey. “This will be our first batch of soap in four years. We are still trying to settle but we have made some soap and within a week it will be dry and ready to sell.”

From a company with between 75 and 100 employees and an annual production of 500 tonnes of soap, Noble Soap now employs just 20 people, 90 per cent of whom are from the former Aleppo factory. This year it has been able to produce about 100 tonnes. The new set-up is an attempt to keep sharing one of Syria’s “treasures” with the world and help those staff members who are left.

“The idea was not to re-establish Noble but to let the workers work again, earn some money and feel dignity,” says Andoura. “We still believe in Syria and its treasures. Our slogan is: ‘When passion becomes a profession’. We are not giving up on this business, we believe in committing to our land through this work. It’s our heritage and it should be shown to people around the globe.”

There is still a strong market for the soap, as well as entrepreneurs willing to take the considerable risks to export it. Mahmoud al-Naboulsi founded Kesabella in 2006 and has been exporting numerous kinds of Aleppo soap across the world for about a decade. To this day, he continues to transport soap from Aleppo and Latakia to Damascus, and then on to Beirut. “The journey from Aleppo to Damascus in particular is very dangerous but we trust in God,” he says from his small shop in west Beirut’s Hamra. “All of our business right now is under risk but we have to keep going and moving, we cannot stop.”

Out of the dozen or so soap factories in Aleppo that Kesabella used to work with, only two are still operational in the city, both in the government-held area. One of these, Dakka Kadima, is relocating to the relative calm of the eastern coastal region Latakia by the end of the year. The others have either collapsed, closed or already moved elsewhere. “We heard that some of the people who know how to make Aleppo soap have been killed,” says Naboulsi. “We don’t know where a lot of the factories’ owners are.”

Kesabella still boasts a huge range of Aleppo soaps, from the purest of the pure – made from 50 per cent laurel oil – to scented varieties packaged in boxes decorated with a map of Syria. But Naboulsi says business is not what it used to be. Before the war the company’s exports were worth $25,000 (€23,300) a month, whereas today their total value is about half of that. “Now we are doing one big shipment every two or three months,” he says.

This slump is largely down to the lack of functioning factories and the logistics involved in getting large quantities out of Syria, not a decline in demand; Aleppo soap remains an iconic and coveted beauty product. “Aleppo soap is popular in Lebanon, Jordan, the gcc and Europe,” says Ludmila Bitar, the French-Algerian founder of the Beirut-based Ideo Parfums olfactory company. She travelled to Aleppo and Damascus in 2010 to launch a collaborative soap-making initiative, seeking to capitalise on the product’s unrivalled reputation. But when the war started it fell apart. “We lost contact with them and it wasn’t possible to work properly together or send them the raw materials,” she says from her chic fragrance shop in east Beirut’s Gemmayzeh area. “During the second winter of the Syrian war [2012-13] the weather was so harsh that a lot of people had to use the laurel branches for fires in their houses to keep warm. So this key ingredient was missing. It became a nightmare to try and collaborate. People were not focusing on business: they were focusing on saving their lives.”

Unwilling to give up on the idea of stocking one of the world’s oldest soaps, Bitar is now in contact with some people in Damascus to try to work out if it would be possible to set up a new production line in Lebanon. This is something Syrians are unable to do due to hefty working restrictions imposed on them by the Lebanese government. For Bitar, this is both a business opportunity and a chance to save something that is part of the Levant’s craft heritage. “Lebanon needs to use this opportunity to make sure that this know-how does not die,” she says. “When these old traditions die out, it’s the history of a country that we lose.”

Aleppo’s challenges are many. The city has been under bombardment for so long that it is hard to see how it will ever return to a place where people once tucked into cherry kebabs and wandered the seemingly endless covered souk. By maintaining the ancient soap production process elsewhere in Syria and across the border – and keeping clients hooked on the product – there is a chance that the industry can be revived when the war ends. When this finally comes, industry will be crucial to any reconstruction process. Its laurel trees may be scorched and its factories looted but the city’s connection to its green gold is undiminished.

4- Translating into profit

The dictionary publisher that is promoting language learning, one word at a time.

If you are a publisher of German dictionaries this should not be a good time to be in business. Smartphones can translate just as well without the added weight in your pocket and doesn’t everyone want to speak English anyway? The owners of Langenscheidt, the iconic German-dictionary publisher, would politely disagree – and they can express their dissent in 35 languages. The Munich-based company dominates the language industry in Germany, claiming 60 per cent of the domestic foreign-language dictionary market and 80 per cent of the foreign-language phrasebook market. “We are the brand when it comes to dictionaries and learning languages in the German market,” says Langenscheidt’s Eckhard Zimmermann.

This market is growing. According to the Goethe Institut, 15.4 million people are currently learning German. The strength of the country’s economy has played a role, as has its prominence in international affairs. As Germany becomes increasingly important, more people want to learn the language. And those numbers could rise thanks to the leading role it has played in welcoming refugees. The Goethe Institut has seen demand for German-language learning grow in 60 per cent of the world’s countries, primarily Asia, Latin American and Africa.

This has benefited Langenscheidt, with exports strongest in the UK, the US, Turkey, Brazil and numerous Arab-speaking countries. That’s despite the fact that, as Zimmermann admits, the name “Langenscheidt” is “not exactly easy to pronounce for non-German speakers”.

Gustav Langenscheidt developed a new phonetic method with his French teacher, which he brought to the market when he launched his publishing company in 1856. An elaborate “L” began appearing on book covers in 1903, followed by the addition of more languages to the portfolio and the market’s first gramophone record for instruction. Years later came travel phrasebooks. Then in 1983 the Alpha 8 appeared: the first electronic dictionary.

But the company’s biggest leap forward came in 1956, when graphic designer Richard Blank created the yellow-and-turquoise logo that became Langenscheidt’s enduring signature. “This ‘L’ has been modernised over time and the serifs have been dropped,” says Zimmermann, though he adds that the process was a delicate one. “If we change anything about the brand it’s approached with caution.”

The most recent incarnation of the Langenscheidt “L” was undertaken by kw43 Branddesign in Düsseldorf. Described by the firm as a “gentle redesign”, it received a Red Dot Award in 2013 for communication design. Thanks in part to this attention to aesthetics, the brand’s image and hold on the colour yellow has become so strong that in 2014 Germany’s high court ruled to protect the trademark hue from use by competitors, after Langenscheidt sued US company Rosetta Stone for attempting to do so.

Langenscheidt’s portfolio now spans more than 35 languages, with thousands of print and cross-media titles and 260 dictionary and interactive apps. Increasingly the company focuses on specialised products, such as b2b learning materials and technical dictionaries in fields such as architecture and chemistry. And, of course, it is constantly renegotiating the balance between print and digital.

Zimmermann started as an editor 30 years ago and is now head of digital business. He’s leading the company with targeted digitisation efforts, which are becoming more prominent as interest in Germany and its language grows. Zimmermann says the media revolution hasn’t crushed the market for print titles but it has meant supplementing these products with digital features. “We now have mixed formats,” he says. “Many say they don’t want to do without the book but will use an app while they’re on the go.”

The new digital market requires an ever more individualised, adaptable and mobile approach to customers, something that is evident when you look at the actions of the company in August 2015. As German authorities and volunteers struggled to communicate with the refugees and migrants at the country’s borders, Langenscheidt made its German-Arabic dictionary available online for free, complete with audio pronunciations. Traffic has not only been “tremendous”, according to Zimmermann, it has also revealed the needs of a new niche market as they unfold.

Now Langenscheidt is working to develop products to serve newcomers and those helping them get settled. “It’s not just about helping refugees but also volunteers and officials, many of whom are also looking for material so they can communicate,” says Zimmermann. “Our short-term goal is to simply enable initial communication but the second phase will be language that aids integration.”

Linguists say that language evolves like an organism, reflecting the concerns and desires of a society as it changes. Perhaps no one recognises this more than dictionary publishers, the stewards of language. In September 2015, one month after the Arabic-German dictionary went online, Langenscheidt published its most popular search words. Among the top 20? “Help”, “love”, “friend” and Zimmermann’s personal favourite: “Welcome”.

5- Place in the sun

The weather-data companies with a clear vision and blue skies ahead.

The forecast for the coming year is in: expect a sunny outlook for the weather-information industry but storm clouds may be gathering for the traditional TV weatherman. Even before IBM’s purchase of the digital and data assets of the US’s Weather Company in October for $2bn (€1.9bn), the weather business was walking on sunshine. It’s a sector with a unique advantage: every human is a consumer. The need for good information is growing and the technology is improving. Big data doesn’t really get any bigger.

But trying to understand the weather business is like trying to establish where the weather comes from. For meteorologists in the US, however, all weather vanes point to leafy Norman in Oklahoma. It’s the centre for extreme weather, home to Tornado Alley and the top-rated University of Oklahoma’s Meteorology programme. It’s also the base for the National Weather Service and Noaa, the two US government storm-prediction services.

With an average of 47 tornados per year, Norman is the Wild West for anyone in the weather industry. Antonio Brizzo of Weathernews says, “If you want to see lions, go to Africa. If you like food, go to Italy. If you want to see a tornado live and big-scale weather, you go to Norman.”

Every country has its Norman and its particular customers and areas of expertise. France’s MeteoGroup – known for accurate and expensive forecasts – serves much of Europe. The UK has the Met Office, offering long-range precipitation forecasts. The World Meteorological Organization in Geneva focuses on climate change. In Japan, Weathernews has dominated the shipping-weather market since the 1970s and Japan Meteorological Agency excels not only in weather but earthquake analysis as well.

And there are more key players in the US: from Pennsylvania, AccuWeather provides world forecasts and sells data to clients such as Samsung Android and abc news; and WSI – part of the Weather Channel’s parent company, now with IBM – rules the aviation-weather industry.

While weather patterns have been affected by changes such as warming ocean waters, it’s a bit of a misnomer to say they are getting less predictable. Forecasting has never been better thanks to enhanced supercomputer models and sharper radars. Today’s dual-polarised radar, for example, can measure microscopic droplets in the atmosphere and determine the type of precipitation that is going to fall.

But it’s not just weather-related technology that has changed the industry: smartphones have also played a role. Weather sensors in mobiles now provide decent measures of temperature, air pressure and humidity. The information gathered by phones, combined with the data from radars, creates a more accurate forecast than previously possible.

Weather-data companies wasted no time in taking advantage of the controls in our pockets and today apps offer the same tools used to forecast in aviation and shipping. Weathernews was early to the consumer market and today has more than 2.7 million subscribers who pay a few dollars a month for mobile-weather content. Its recent acquisitions of crowd-sourced apps in China, France and the US give it direct access to 10 million people in 172 countries, whose phones send back localised weather data. Director Tomohiro Ishibashi says, “My dream is to create the world’s biggest weather communication company, where forecasts are made from the ground, not the sky.”

Consumers won’t really care where the forecast is made as long as it’s accurate. Spare a thought though for the humble TV weather presenter, a staple of news bulletins around the world: your smartphone may be about to put them out of a job.

6- Royal flush

The Malaysian families getting ready to return to the spotlight.

Malaysia’s royals may not have the global recognition of UK princes Harry and William, or the Hollywood style of the Monégasque’s leading family, but you may be hearing a lot more from them in the coming months. They are not happy sitting on their hands and smiling politely any more: they want to flex their muscles. A beleaguered prime minister is in their sights and they’ve got the cash and connections to get what they want.

“Basically the only people in the country that have power are the royal families and prime minister Najib Razak,” says political commentator Murray Hunter. Nine of Malaysia’s states have their own royal family but the power they have is “residual”, he adds.

But that is beginning to change. Some of those once acquiescent royals are exasperated with Najib, who hasn’t explained how almost MYR3bn (€655m) wound up in his account from state-owned investment fund 1MBDB. The wealthy PM – whose luxury-loving wife has been dubbed “the first lady of shopping” – appears disconnected from his people. His inability to deal with the scandal has sparked an emergence of political activism from the sultan set.

“They see themselves as individual leaders having all sorts of privileges but collectively they have more power,” says Asia Sentinel editor John Berthelsen. “So when the Council of Rulers get together to issue a statement that the prime minister should address the 1MDB issue and an investigation should proceed, that is a powerful message.”

But these unruly sultans, whose powers were strangled by former PM Mahathir Mohamad, also have other preoccupations in a region once heralded as “the land of gold”. “They say in terms of wealth that the Malaysian royal families are up there with the British queen and the Thai king,” says Hunter. The latest royal splurge saw Johor sultan Ibrahim Ismail investing in the world’s most expensive Mack truck. This heavy hauler has gold trimmings and a paint job to blend in with the sultan’s 52-foot racing boat, which the truck was modified to tow. Yet a man should never be judged on his truck alone. When he’s not playing Xbox in his Mack’s cabin, Sultan Ibrahim is doing business for his home state. At the moment he’s literally raising an island out of an ocean, working with property developers from Malaysia and China on the multibillion dollar Forest City land-reclamation project.

Yet Sultan Ibrahim isn’t too busy for affairs of state: it’s in Johor that the loudest royal roar against Najib is resounding. “When Najib fired his deputy Muhyiddin Yassin for speaking out against him over the 1MDB debacle, the sultan sent his personal helicopter to fly him back to Johor,” says Berthelsen. “This was quite the gesture. Ibrahim is a powerhouse in that state like no sultan there before.”

This powerhouse’s son and heir, Tunku Ismail, has also stuck the boot into Najib. The prince, whose role model is Fidel Castro, wields grassroots appeal through his affiliation with Johor’s football association. Distancing his family from the political mess in Kuala Lumpur, he warned that if the terms of Johor’s federal membership were ever breached, his home state had every right to secede from Malaysia.

But Johor’s secession is unlikely, says Andrew Harding, director of the Centre for Asian Legal Studies at the National University of Singapore. At the heart of the royal family’s issue with the PM is that old devil, pride. “The leading people in Umno have often been Johor people and they feel that they have some ownership of Umno,” he says. “This is being taken away from them by a corrupt and unaccountable leader and they want to get rid of him.”

This is unlikely to result in political change though, says Hunter. “The royal families are state people and they aren’t united enough to make a bold statement.”

7- Beat about the bush

The Australian newspaper that is putting the country – and its crocs – on the map.

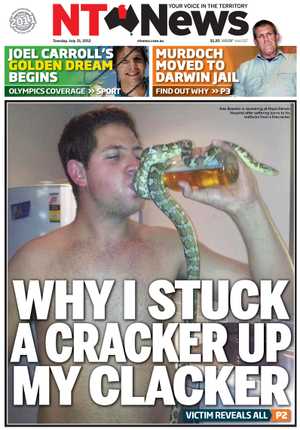

Australians have long enjoyed projecting to the world an image of themselves as rugged, laconic bush-folk, wringing a living from a vast and unforgiving wilderness. The reality is that they – OK, we – are a nation of cossetted urban latte-slurpers, few of whom have ever skinned a goanna for breakfast. If the stereotype does live anywhere though, it’s surely in the Northern Territory, a region more than twice the size of France, home to about half the population of Lyon. They are by definition unusual people – and they are served by an unusual newspaper.

“It’s unpredictable, that’s for sure,” says Rachel Hancock, editor of the NT News. “The Territory produces some amazing and very different stories to anywhere else in the country. It’s partly the geography and weather but mostly because Territorians don’t take life too seriously and like to have fun, so we try and have fun with them.”

The NT News was founded in 1952 and has been owned by Rupert Murdoch since 1960. For most of that time it has been the only daily serving the Northern Territory capital of Darwin, generally doing so with little impact elsewhere in the country – Darwin is further from Sydney than Istanbul is from London – let alone the rest of the world. In the 21st century this has changed due to a combination of something new – the internet – with something the Territory has possessed since the Mesozoic era.

“I’m not going to lie,” says Hancock, “when a great croc story or picture lobs on the news list I’m somewhat comforted. But it really has just evolved. The best thing is, because of that reputation, readers are constantly sending us stories and pics, so it makes our job easier.”

Hancock is too modest. Though any encounter between human beings and one-tonne prehistoric reptilian death machines can barely help but be compelling, the NT News presents them brilliantly, with a splashy visual and an editorial tone entirely at home on the internet yet also evocative of a long tradition of dry, somewhat self-mocking Australian tabloid journalism that once flourished on the pages of journals such as The Truth and The Picture.

It has done wonders for the NT News; in 2014 it was Australia’s fastest-growing newspaper with 55 per cent growth in digital readership. In 2015 its Sunday edition ended up being the only one in the country to have increased circulation. About a quarter of its following on social media is overseas. It has opened a shop, offering fare tailored to its image: singlets and beer-can holders emblazoned with memorable headlines. A book, What a Croc!, has compiled some of the paper’s best-loved front pages. On first flick this may seem an exercise in finding out how many puns can be wrung from the paper’s favourite fauna; a crocodile stored overnight in a cell inspires “Jailhouse croc”.

While these zingers doubtless prompted richly deserved high fives around the sub-editors’ desk, the still greater joy of the NT News is its treatment of stories in which it has to be suspected that an excess of sunshine and/or alcohol has been a factor. Stories, that is, in which one or more protagonists would be diagnosed, in the local vernacular, as having “gone troppo” (troppo, adj: contraction of “tropical”, applied to person/s whose behaviour suggests they’ve been outside too long without a hat on). For all its facility with wordplay, the NT News understands that sometimes there is no improving on the bare facts of the case: see “Best man left bleeding after being hit in head by flying dildo”; “Sailor bashed for cheeseburger”; “Man stabbed with fish”; “Croc eats boat”.

Between all of these, the newspaper takes pride in solidly covering its local beat. “It’s a difficult balance,” says Hancock. “You do too much of the quirky stuff, you’re criticised, but too much of the hard stuff and you’re told to lighten up. We are the voice of the Territory and we need to reflect the issues that affect Territorians. We try and mix it up, light and shade.”

It may seem counter-intuitive to suggest that there are lessons for more self-consciously worthy media outlets in the success of a newspaper that is also not averse to running with the odd too-good-to-check ghost story. But there are: to prosper in an over-run and infinitely clamorous media landscape, every outlet needs an idea of itself in which it has complete confidence and an identity that is quickly understood – who we are, who we’re for.

8- Distinctively average

The German village whose normality makes it a prime subject for market research.

The village of Hassloch in the Rhineland-Palatinate region of southwest Germany is quaint and peaceful. Its main thoroughfare is flanked by centuries-old half-timbered houses and on sunny afternoons birds flit past the church on its quiet central square. During the day many of its residents work in the nearby city of Ludwigshafen, home to chemical giant basf. That leaves the town largely to its elderly residents, who tend to greet each other with a friendly “Guten Tag” when they pass on their bikes.

At first glance the village of about 21,000 resembles a cookie-cutter version of small-town German life, albeit with a conspicuously self-deprecating name: “Hassloch” translates as “hate hole” in English. But Hassloch, it turns out, is both more average and more distinctive than it seems.

For Andreas Völtl, the director responsible for real-life test markets at the Gesellschaft für Konsumforschung (GFK), Germany’s top market-research institute, Hassloch’s averageness is a hugely valuable asset: it has helped his organisation turn the village into one of Europe’s most distinctive laboratories for consumer products. “When a company wants to reach the masses it is looking to the middle of society,” says Völtl. “Hassloch is the middle.”

The village, which is about 50km from the French border, is so demographically, geographically and economically similar to the German mean that it has become known as the country’s most average municipality. Hassloch’s score on the purchasing-power index, for instance, is only one point away from the national average; and because of its demographics, the village’s exit polls are sometimes used to help predict national election results.

For the past 29 years the GFK has granted large companies from Unilever to Bahlsen the opportunity to test not only their products but their entire marketing strategy on Hassloch’s residents. As a result, Hassloch is a curious bubble: its supermarkets contain food items that are available nowhere else in the country and residents are exposed to radio, print and online marketing for products that are still months away from their national launch. “What makes Hassloch so unique is that it allows companies the possibility to put all elements of their product launch to the test,” says Völtl.

The test market is headed by Bettina Bartholomeyzik, a 56-year-old who works in an office next to a dentist’s on Hassloch’s main street. When a company pays the GFK to test its products she organises their distribution to the town’s supermarkets. “It’s very expensive to introduce a product nationally and it can be embarrassing for a big company to pull it off the shelves, so they test it out here in advance,” she says.

In Hassloch, companies can experiment with a product’s shelf placement, packaging and adverts. In 1986 the GFK was partly drawn to Hassloch because it was one of the first communities in Germany with cable-television access, allowing the company to tap into the village’s incoming broadcasts. Today Bartholomeyzik’s employees control the town’s TV advertising from a studio lined with monitors, computers and shelves of old tapes.

Through its deals with local supermarkets the GFK is able to monitor how well the company’s advertised products do with its “average” shoppers. The local branch of the Edeka supermarket chain is equipped with technology that allows participating households – about a third of the village – to swipe a card when they shop, sending information back to the GFK’s headquarters in Nuremberg.

Aside from the introduction of technology to analyse data and tweak ads, Hassloch’s test-market has changed little since its inception. However, in 2016 and beyond it will face a growing challenge from so-called “virtual test-markets”: cheaper, simpler alternatives to real-life consumer laboratories. In the summer of 2015 the GFK acquired a Swedish company specialising in “virtual shopper research” – 2d and 3d computerised shopping simulations – but it remains convinced that Hassloch is the most all-encompassing way of determining the value of a product. “In Hassloch you can test everything,” says Völtl. “It is a cut-off world.”

Many Hassloch residents view their “average” status with both humility and pride. Bettina Finco, a 53-year-old mother of two, has been taking part in the GFK experiment for two decades. Her parents were also test subjects and being a tester, she argues, is a natural part of being a Hasslocher. “There is good average and a bad average,” she says. “We consider ourselves to be the good average.”

As Finco says, Hassloch is a pleasant place to live: it has good schools, high levels of community involvement and a friendly atmosphere. The most newsworthy event to take place in the village recently involved an escaped cow. “It has everything you need to live well,” she says. “We just happen to decide what goes on German shop shelves.”

9– Altar-natives

The Greek churches and their plots of land that offer another option for your future house.

Take a drive from Kifissia down to the Athenian Riviera at Vouliagmeni and you’ll experience one very Greek thing on your way to another: you can’t get to the well-tended sandy beaches without passing a hoary old loophole.

Just what is that by the side of the road? An olive grove buzzes past. Not that. This again. What on earth are all those churches doing squashed up cheek by jowl against each other? Is it the most devout village in the world, boasting the tightest concentration of small churches, all higgledy-piggledy and packed on top of each other? A church for every worshipper. It sounds like an Old Testament quote; a bit of Orthodox demagoguery or a neo-con promise. But it’s not. It’s the depot of a church factory and the churches that this factory builds represent that ancient Greek tradition: the loophole.

Now, there are get-out clauses and dodges; there are unlevel playing fields and strange discrepancies. But this is really wonderful. In Greece it’s possible to buy land on which to build a house. But to avoid the red tape and expense of going down the official route and getting the correct permissions and utility connections from the government, you can take the path of least resistance and the spiritual high ground: purchase a prefabricated church, get the church authorities to give you the permissions to hook it up to the mains and then build the big house you always wanted for the plot as a secondary, attendant structure – a humble dwelling serving the church, if you will – and hallelujah! You have your house, rigged up and ready to rock, as well as a nice little church in the garden for your daily prayers. Of course you use it for worship if anyone asks but – heavens – it’s also so damned useful for storing the lawnmower and the rake. Bob’s your uncle. And God’s your planning officer.

When I say, “This is really wonderful”, I should also point out that the practice is, in fact, becoming too good to be true. Suspicious of such a bricks-and-mortar/nave-and-altar way of approaching religious rectitude, the Greek authorities have cracked down on the practice. But the supply and demand for prefab churches stays strong. We’re used to hearing that the church is powerful in Greece but this is ridiculous. Greeks want to build houses wherever they own land, hence the suspicious score of forest fires followed hot on the heels by house building. As we drove down Varis-Koropiou Avenue on the way to the beach, my Athenian friend told me that Greeks tend to shrug at this sort of “soft corruption” because they all practice it in their daily lives, either brazenly or just to get by and make things work in a country where things often don’t. Hell, there’s even a hole in this loophole.

In the meantime, maybe in the springtime, get thee to thy church factory while you still can. You can order any type, from Byzantine to Cruciform, with island-style flourishes and basilicas, or go for a miniature Hagia Sofia (with no joins). It seems that the great Greek church loophole is a dying sacrament. Is nothing sacred?

10– Former glory

How will we be safer in the years to come? An old Nato chief has a suggestion.

Former politicians used to retire. There would be memoirs, a light bit of after-dinner speaking, the occasional wheeling-out to comment on great matters of state. But many of the politicians who reached the top in the 1990s and 2000s were a generation younger than their predecessors. Out of office in their fifties or early sixties, they are now too young to become elder statesman.

Anders Fogh Rasmussen is a “former” two times over: ex-prime minister of Denmark; ex-secretary-general of Nato. A fresh-faced 62, he is managing to keep himself busy. There is, of course, the inevitable book. Due out in the US before the presidential elections it will, he says, be “a kind of message to the next president”. Part of that message will almost certainly be about the threat posed by Islamist extremism and, in particular, Isis. Rasmussen oversaw the drawdown in Afghanistan but was also prime minister during the Danish cartoons crisis. He knows a thing or two about the strengths and weaknesses of a military fight as well as the tensions that can grow between communities.

“I think we need a reinforced military fight against Islamic State.” It needs to be “eradicated”, he says. “I also stress that I don’t see a long-term military solution to the problem in the Middle East. We need a political solution.” But even a former Nato chief struggles to explain how that can happen. He wants troops on the ground but local ones, not foreign. Yet he admits the options aren’t great: the Kurds won’t go any further south and attempts to arm and train moderate rebel groups have, so far, failed.

“We can’t just accept that,” he says. “We have to do something. There is no alternative to reinforcing the fighting against Islamic State.” The question of how is left hanging in the air.