Future of farming / Global

Fertile markets

Rural depopulation is the flipside of the urban success story but there are ways to make sure it doesn’t leave city-dwellers bereft of fresh produce or their age-old connection to the soil. Here are three firms ploughing their own furrows to get the countryside growing again.

A seminal shift occurred in 2009, when the global urban population eclipsed the rural population for the first time in human history; it’s a worldwide trend of urbanisation that shows no sign of slowing down. For agricultural businesses, this means fewer people are there to till the fields and drive the tractors. Kubota, a Japanese agricultural machinery-maker, is partnering with farms to prove that new technology can counteract a dwindling rural workforce.

At the same time city dwellers are yearning for the land. You can see this in the popularity of LandLust, a magazine published by Landwirtschaftsverlag in Germany that focuses on the joys of a bucolic life. Or Komsukoy, a firm that helps Istanbul residents grow fruit and vegetables on smallholdings away from the urban hubbub. As our cities swell and rural areas empty, we need to keep the countryside vital.

1- Landwirtschaftsverlag

Münster

You might expect the CEO of Landwirtschaftsverlag, Germany’s leading agricultural-magazine publishing house, to dress and behave a little more, well, like a farmer. But today Hermann Bimberg sports a blue suit and a shirt, and his office on the top floor of a sleek five-storey building in a prosperous suburb of Münster is full of modern art.

But appearances can be deceptive. Bimberg, who has run the Verlag for 14 years, studied agricultural science. When he’s not running a publishing juggernaut with a staff of 500 and revenue of about €100m he can be found on his 110-hectare pile in the countryside near Dortmund, which has been in his family for more than 200 years.

The publisher was a one-title operation for more than a century, its weekly Wochenblatt the sole product. It made a bid for national circulation in 1970 with full-colour monthly Top Agrar, aimed at farmers across Germany. Now its stable includes dozens of titles covering everything from farm machinery to equestrian sports and dairy cows.

The publisher’s halls are lined with framed covers and abstract artworks. It’s a fairly urbane setting, the life-size fibreglass cow on the second floor aside. Yet almost every member of staff has farm experience: they’re either farmers themselves, grew up on farms or have degrees in agricultural sciences. Some, including Bimberg, tick all three boxes.

Ludger Schulze Pals runs flagship monthly Top Agrar from a pristine corner office on the second floor. He started his career as an intern here before leaving to earn a doctorate in agriculture and spent more than a decade working in a variety of ministries as a speechwriter and press spokesman. “Everyone teases me that I left as an intern and came back as the boss,” he says with a smile.

Schulze Pals’ years treading the halls of power are a real asset: German farmers need to keep abreast of European, national and regional politics. He grabs the November issue to prove the point. The three-pager he penned on the politics behind the milk-price crisis gripping Europe’s dairies walks readers through the key players.

Down a floor in Wochenblatt editor Anselm Richard’s office, the vibe is different. Richard wears jeans and a wrinkled blazer; his desk is piled high with papers, burying his iMac. Standing in front of a wall-mounted map of North Rhine-Westphalia, he says nearly every farmer in the region gets the Wochenblatt. It’s been published weekly, save for a brief period after the Second World War, for 170 years and local deals for cows, sows and soy are made based on its Market Telegram. “Farmers don’t need minute-to-minute prices,” he says. “Our readership is already fairly old and conservative. They rely on the print product.”

Yet while the print offering remains strong, editors at Landwirtschaftsverlag have to bridge the gap between old-fashioned farmhands more comfortable around a combine than a computer and a new generation of digital natives tweeting from their tractors. Take the 32-page package in Top Agrar about all things swine, which includes a feature on burnishing your cruelty-free credentials using Facebook – plus a gentle explanation of what Facebook actually is.

Back in his office, Bimberg praises his employees’ embracing of the web. Some of the Verlag’s newest ventures aren’t included on the rack of magazines in the lobby, such as LandReise, a travel platform for people who want to spend holidays on farms. Its biggest digital venture so far is traktorpool.de. Launched in 2001, it’s now Germany’s leading classifieds site for used farm equipment. Too niche? “It’s actually a big earner for us,” says Bimberg. After all, when you’re in the market for a gently used Putsch Beetmaster mobile beetroot washer and corer, a bargain at €211,820, eBay is probably not going to be much help.

Notes: New crop

Ute Frieling-Huchzermeyer, editor in chief of LandLust, is excited – and with good reason. It’s a crisp autumn day outside her office on the ground floor of Landwirtschaftsverlag, the perfect time of year to launch an English edition of the country lifestyle title that’s taken over the German magazine world.

Since it launched in 2005, the bimonthly’s circulation has soared to about 1.1 million copies. Its leisurely pace and focus on topics other magazines might overlook succeeded where flashier competitors failed. “We’re focused on authenticity,” she says. “Food photos aren’t styled and we don’t use models.”

Frieling-Huchzermeyer is convinced that UK readers will love the finished product. “People spend their working life online,” she says. “You need a balance. Quality journalism, great photos and magazines that are comfortable to read have bright futures.”

2- Komsukoy

Turkey

The neighbours didn’t quite know what to make of Komsukoy’s three founders when they first began tilling the fields. They certainly didn’t look like the hardened farmers usually found in Cumhuriyet, a conservative area on the eastern outskirts of Istanbul. In fact the trio normally run an advertising agency in the city; out here they like to play jazz across their fields of cauliflower, carrots and broccoli.

“At first it was hard to find people to work for us around here,” says Ogulcan Atay, who launched Komsukoy in 2014 with siblings Ozden and Ugur Akyildiz to give Istanbulites the chance to become small-hold farmers. “Now they all want to work here,” he adds as two women in colourful headscarves trundle past to the strains of Fela Kuti. “It has become a very attractive option.”

Komsukoy’s subscribers sign up online, paying TRY3,250 (€1,050) a year to rent a plot of land where they can grow up to seven different crops of their choosing. Alternatively they can select rows of plants to rent across several fields for a more diverse haul. Every day up to 15 workers from the surrounding villages weed, water and tend the crops until they’re ready for harvest. The produce is then delivered the same day to members’ kitchens in Istanbul.

But the magic of Komsukoy is that the members are also encouraged to spend time on the farm tending their own crops. It is not uncommon for them to arrive in suits from the city, ready to roll up their sleeves and get to work, trowel in hand. Otherwise they can manage their crops remotely via an online application, deciding what they’d like to plant and when to harvest. “We needed a simple, easy way to get people and their children into farming,” says Ozden.

Patience is key to this business. Members are told from the start that there’s always a chance a bad spell of weather might produce a slim harvest. Komsukoy was founded as a response to the increasingly industrialised farming processes being used elsewhere in Turkey and so chemicals remain strictly off the agenda. Instead the team employs “companion farming”, which enlists the natural properties of certain plants to keep away bugs and create soil humidity, or act as a compost when left to wither.

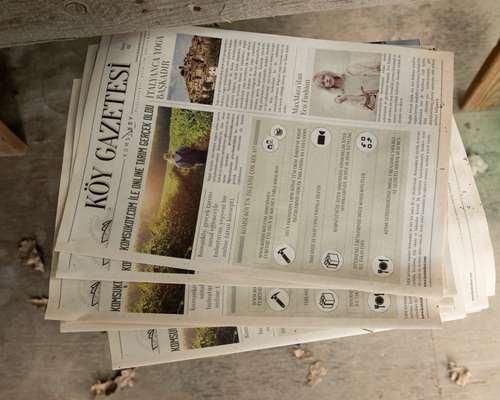

Growing a community, the founders say, has been essential to the venture’s success. Members are invited to regular meetings where a day spent working in the fields is followed by a meal at Komsukoy’s onsite café The Village, usually rustled up by one of the members; unsurprisingly, there are a few chefs on the subscriber list. A members’ newspaper, the Koy Gazetesi, includes recipes based on whatever happens to be growing at Komsukoy in any given season.

The farm is now full, with 150 members signed up and a growing waiting list. Komsukoy has also attracted a number of corporate members as farmers and several restaurants in Istanbul receive their produce from here each week. “This is about providing healthy food but also about getting people to be part of production, not just consumption,” says Ozden.

“Komsukoy allows people to meet nature and see how farming works,” says Atay. It is a feeling that’s shared by Emre Buga, an anchor at one of Turkey’s television stations, who joined Komsukoy at the beginning and currently has rocket, radishes, cabbage, broccoli and leeks in his fields. “I miss the summer because I haven’t tasted watermelon like those grown at Komsukoy before,” he says. “I once found a snail in my spinach and I was so happy because it meant I was sharing this with nature; it means these crops are alive.”

3- Kubota

Japan

Demographics are doing Japanese agriculture no favours: a dwindling, ageing population of farmers means fewer people are working larger farms. Factor in the deluge of imports that could come if the 12-nation Trans Pacific Partnership (TPP) trade agreement is ratified and it is likely that more farmers will leave the rural life behind.

None of this should be good news for Kubota, Japan’s largest manufacturer of agricultural machinery. And yet the company has decided to take the battle to the rice paddies and get involved in the business of farming itself. It has two farms up and running and by 2019 it will co-own 15 in Japan, totalling about 1,000 hectares of land.

These partnership farms will serve as a testing ground for new ideas and machinery. The jewel in the crown is the Kubota Smart Agri System (KSAS), designed to bring agriculture into the 21st century. Using the handheld device, made by Kyoto-based Kyocera, Japanese farmers can now track the planting and harvesting of crops precisely. Kubota’s KSAS-compatible combine harvesters can measure protein and moisture in rice crops and use the data to calculate future fertiliser requirements.

Tests between 2011 and 2013 showed that this close management of farms improved rice quality in just one year. “One farmer can be looking after 100 or 200 fields now,” says Yasuo Kammuri, who manages Kubota’s farm-machinery operation in Japan. “Once the worker completes the task, the business manager or farmer can check immediately.”

The agriculture sector hasn’t had a good press in Japan, where it has been seen as too dependent on government subsidies and import tariffs. However, Kammuri says the challenges of modern farming here present opportunities. “We can expand into greenhouses and rice export,” he says. “Our aim is to provide a good environment for farmers; we don’t want them to leave the industry.”

Notes: Thinking bigger

Kubota has long focused on the needs of rice farmers who use light tractors but it has just launched the M7001. The 170HP tractor can handle European or US upland wheat farms and is the first of its kind built by a Japanese manufacturer.