National Gallery Singapore / Singapore

Portrait of a nation

The island state is not used to letting people do anything they want and that means it’s been stuck with a moribund arts scene. But the new National Gallery aims to change perceptions of the country at home and abroad. Here’s how.

Whether it is the Tate, the Met or Musée d’Orsay, art galleries play a big role in contributing to the cultural capital of the great metropolises – and countries – to which they belong. So when the National Gallery Singapore opened its doors in November 2015, it was a reflection of a nation’s ambitions after 50 years of sovereignty. The museum holds the world’s largest public collection of Southeast Asian art from the 19th century to the present – a proclamation of Singapore’s aspiration to be the region’s artistic mecca.

“The National Gallery Singapore aims to be a leading visual-arts institution,” says Eugene Tan, the gallery’s director. “We want to create a dialogue between the art of Singapore, Southeast Asia and the world.”

The gallery, born out of a government policy paper, is the latest project in the country’s efforts to shed its sterile image as a commercial hub fuelled by office drones. The Renaissance City Report, released in 2000, looked at “internationalising the Singapore arts scene”. Unlike the Singapore Art Museum, founded in 1995, the National Gallery has a Southeast Asian rather than a national perspective, bringing together a collection of seminal works in a way that has never before been attempted on such a scale.

Finding the right venue was the first task. For the gallery to resonate with citizens and travellers alike, it had to be accessible while possessing a gravitas befitting the region’s great masterpieces. Eventually the former site of the supreme court and city hall was selected. “The brief was to inject something new and modern into these structures, which have formidable histories,” says architect and facilities director Sushma Goh, alluding to the neoclassical buildings’ fame as the spot where Japan relinquished its occupation of Singapore at the close of the Second World War.

Paris’s Studio Milou worked with Singapore-based CPG to transform the two grand civil-district buildings into a single art space. “This is precious real estate for the nation,” says the gallery’s CEO Chong Siak Ching, who makes up for her lack of a professional art background with years of experience as a property developer. While the National Gallery is not her biggest project financially, she says it’s the most personal. The final result incorporates state-of-the-art architectural interventions. Two sky bridges connect the buildings and a “tree” has been planted in between: a metallic column that springs from the ground and expands into a vast aluminium-filigree canopy, which provides shade for visitors while allowing for sunlight to flood the space. “They look beautiful but they’re actually a very solid structural solution to hold up the roof,” says Goh. “We didn’t want too much resting on these old buildings.” The result is spectacular; this is Singapore’s response to the Louvre’s glass pyramid and it is a work of art in itself.

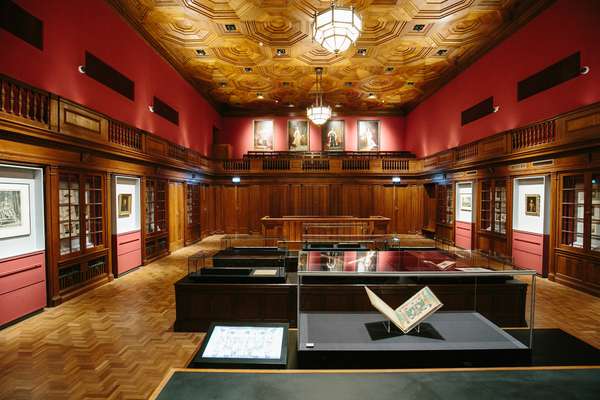

Other nips and tucks include the installation of skylights to suffuse the interior with natural light, plus ample natural-wood surfaces that contrast with the grey of the dominant plaster. Meanwhile, Singapore-based design agency Lekker has given the old courtroom benches a contemporary update to create public seating. The stereotype of big-government art galleries being underfunded, crummy and dim places has been dispelled; the National Gallery is a breath of fresh air.

The best form of advertisement may be word of mouth but a trinket or two for friends back home never hurts. Singaporean hospitality entrepreneur Loh Lik Peng has collaborated with design agency Foreign Policy Design and retail-consultancy firm Luxasia to smarten up the museum giftshop. Their outlet, Gallery & Co, sells reprints of famous works along with unique souvenirs, from tote bags to coasters created by Singaporean designers exclusively for the gallery.

Many will visit the gallery based on the architectural and historical merit of the buildings alone but it is the artworks and exhibitions that will determine sustained success. The National Gallery comprises two permanent exhibitions: the Singapore gallery and the Southeast Asian gallery. Curatorial director Low Sze Wee turned to other museums and private collectors across all 10 Southeast Asian countries – and further afield to institutions such as Japan’s Fukuoka Asian Art Museum and Amsterdam’s Tropenmuseum – to borrow pieces that would flesh out the exhibitions.

Laid out chronologically for a comparative approach and with works from different nations displayed side by side, the pressing issues of each epoch become immediately identifiable. “We didn’t want to just present the national frameworks; the home countries are already doing a very good job of that,” says Low. “More interesting is how common themes and interests, such as the complex relationship the colonies had with their respective colonialists, link artists from across the region.”

Finding the key masterpieces to showcase is an ongoing process that has curators spending years zipping back and forth across the subcontinent to coax institutions such as the Vietnam Fine Arts Museum and the National Museum of the Philippines into parting temporarily with their national treasures. Some of these, such as “Christian Virgins Exposed to the Populace” by Filipino artist Félix Resurrección Hidalgo, are on renewable one-year leases.

“They trust us with the work; it’s more a case of whether the national galleries in the other countries can do without them,” says Low, adding that the gallery wanted loans spanning years instead of the usual three to four months. “We want our visitors to have time to get acquainted with the iconic pieces of the region.”

There is an oil-on-canvas work on display that encapsulates what the gallery is trying to achieve. Scribbled on the blackboard in Singapore social-realist painter Chua Mia Tee’s “National Language Class” is the following phrase: “Siapa nama kamu?” It means “What is your name?” in indigenous Malay; apt, as the issue of regional identity is exactly what the gallery sets out to address.

That task poses its own challenges but, while the Singaporean authorities are known for heavy-handed censorship, curator Adele Tan points to an installation that flirts with gender identities. It is an indication that the gallery has been given more leeway to push boundaries in a country where homosexuality is technically illegal, although the law is never enforced. That said, government-affiliated institutions have a history of buckling under pressure from public complaints; the test is whether such works are still on display in a year’s time. Furthermore, compared with the New York Met’s gargantuan vault of two million artworks, the gallery’s collection of nearly 10,000 looks anaemic. More sculptures and installations are needed and, while the curators are working to bolster the 19th-century collection, success is also dependent on its regional partners; will they continue to loan Singapore their best works? And will the gallery’s young staff be too inexperienced to be taken seriously by the art world’s old timers?

Whatever the outcome, the institution has fixed its sights on opportunities. “By situating the narrative in the region within a complex, cosmopolitan outlook the gallery will draw cultural tourists and academics alike,” says Bridget Tracy Tan, director of Southeast Asian arts at the Nanyang Institute of Fine Arts. “It’ll expand on the dialogue defining Southeast Asian art.” A co-curated exhibition with Paris’s Centre Pompidou is in the pipeline.

The dearth of scholarship on regional art gives the National Gallery Singapore a blank canvas to carve its own niche as the destination for all things artistic in Southeast Asia. Singapore – a country that takes pride in having engineered its own economic miracle – hopes it can replicate this success in the world of art.

Notes: More Asia collections

While the National Gallery Singapore is the first of its kind to take on a regional approach, there are other institutions that offer deep insights into their national art histories.

Vietnam National Museum of Fine Arts, Hanoi. This is set in a colonial-era house and showcases a mix of historical, modern and contemporary works.

Agung Rai Museum of Art, Bali. Located in Ubud on the island of Bali, this is the place to go to peruse masterpieces of Balinese art, ranging from traditional woodworks to batik.

National Art Gallery, Bangkok. Housed in the former royal mint, the key works from the Thai national art collection from the classical period to the present can be found here.