The book fights back / Global

Read all about it

In the US, Germany, the UK, Indonesia, Hong Kong and China, a renewed interest in the printed word means more books are being dusted off and fewer e-readers are being turned on. Is this a new chapter?

Are we on the same page? Did you really expect to be reading on paper 10 years after Amazon’s Kindle launched? Well, here we all are. Each of us will have our own reasons for holding onto paper but we are not alone. Print will be getting an injection of youthful vigour in 2016; data, that cold, hard, digital source of information, tells us so. So sit back; the story you are about to read is a global journey through publishing full of ups, downs, twists and turns.

Page one begins in September 2015 with a titillating headline in the New York Times: “The plot twist”. E-book sales are falling in the US; at the same time, independent bookshops are on the rise. For added intrigue, major book publishers are buying warehouse space for larger inventories. But think twice before you throw your Kindle on the fire: let’s first find out what’s really going on with American readers.

In the publishing world’s biggest market, print is still the most popular format according to the Pew Research Centre. Yes, numbers tend to move up and down each year but publishers report stability in adult book divisions. Meanwhile, e-book reading is indeed plateauing and the market for e-readers is being consumed by smartphones as consumers balk at carrying multiple devices.

Alas, a happy ending for books in any form is not guaranteed as the overall number of adult readers has dipped. But the demographics make better reading: those aged 18 to 29 are the most likely to have read a book, both in print and digital form. Some in the industry speculate that “digital natives” exposed to screens all day cherish an opportunity to turn away and turn off. There is a new consensus in the industry that print and e-books have a complementary rather than cannibalistic future among younger readers.

Professor Naomi Baron of the American University in Washington has surveyed 400 university students in five countries for her recent book Words Onscreen: The Fate of Reading in a Digital World. “What amazed me was how many millennials all over the world believe that reading in print is a different and preferable experience to reading in digital,” says Baron. A staggering 92 per cent of those surveyed said their concentration is highest when reading in print.

Across the Atlantic, the digital-book business in the UK and Germany – Europe’s two largest publishing markets – is getting a makeover. In 2015 the UK’s biggest bookseller, Waterstones, stopped selling Kindles due to lack of demand. A year earlier Pearson, the world’s largest publisher, sold back its stake in Barnes & Noble’s Nook e-reader for a third of the original price. Back in 2013, a competitor to Amazon’s Kindle platform emerged in Germany. Tolino is a digital reading device and platform created by Deutsche Telekom and four German booksellers. Offline booksellers can use it as an extension of their own shop, avoiding the showroom effect (browsing in store and buying from someone else online). It is attracting other German booksellers and expanding into Belgium, Italy and the Netherlands; the brand accounts for about 40 per cent of the German e-book market.

Richard Charkin, an executive director of Bloomsbury Publishing and president of the International Publishers Association, is unmoved by US data charting a digital downturn. Self-publishing and genres such as romance and westerns remain hugely dependent on digital sales, he says: “Taking the totality of the world, digital reading is going to grow and grow.” During the first half of 2015, print sales generated 79 per cent of Bloomsbury’s revenue and 77 per cent of the year-on-year revenue increase. Even so, Charkin says publishers are intellectual-property traders, not manufacturers of books. Customers will ultimately decide which way the industry goes.

Juergen Boos agrees: publishers are not talking about format, says the director of the Frankfurt Book Fair (FBF). During the week, the FBF is for trade; the chat is about content and rights. The book stalls exist mainly for the weekend consumer crowd, who still want to leaf through a hardback. The feeling is that the book industry in Europe has avoided the disaster that hit the music industry and is enjoying a period of healthy stability.

Morale is high and Boos’ attention is piqued by possibilities in international markets. Under his decade-long tenure of the fbf the majority of German exhibitors have become international. Large numbers now travel to the fair from Asia and Latin America; Indonesia was made the guest of honour at the latest FBF. He has recently returned from a trip to Southeast Asia to meet the young people getting into publishing.

One of those is Laura Prinsloo, who was 27 when she left her finance job in New Zealand to join down-at-heel Indonesian print publisher Kesaint Blanc. Now she’s 32 and the company has grown 200 per cent under her direction. Indonesia’s enviable adult literacy rate is kept busy by a social-media frenzy but co-publishing is proving a profitable addition to its core foreign-language training books; the Japan Foundation, for example, is financing a book on how to learn Japanese.

Back in London we meet Shumi Bose, the founder of the Real Review alongside Jack Self. “As digital publishing reaches maturity we have got better at processing different kinds of information in different formats at different times of day; it is not one or the other anymore,” says Bose. Their high-quality print publication, launching in 2016, owes its origins to a decision by the Architectural Review to discontinue its review section (the world’s oldest existing architectural publication is going solely digital soon). Writers will be paid using a crowd-funding campaign that easily exceeded its target.

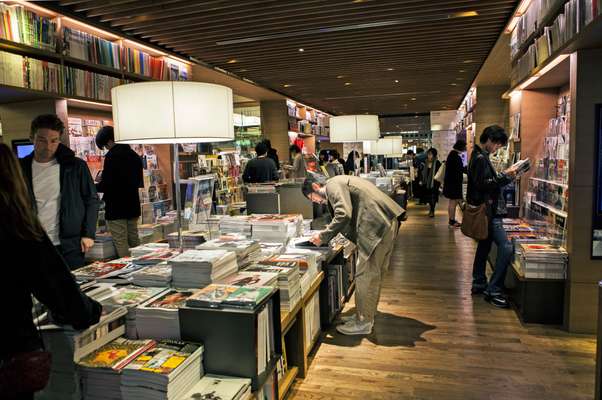

Bookshops themselves face a mixed future. More than one million people attended the consumer-driven Hong Kong Book Fair, a few months after book chain Dymocks closed the last of 10 shops in the city due to unaffordable rents. Taiwanese bookshop Eslite, however, is in expansion mode. Its store in Hong Kong turned three in August 2015 and a new shop in Suzhou, near Shanghai, marks its first foray into the mainland market. China is now the second-biggest market for books in terms of revenue and titles published.

“When we create a space we think how to make people comfortable,” says Allen Su, vice-president of Eslite. “When people feel comfortable, they stay. When they can get something from a book, like wisdom, they buy it.” Eslite has never stocked Kindles because e-reading has so far failed to grab the eye of consumers. A version of Tolino called Super Book City launched at the same time but it has not enjoyed the same success.

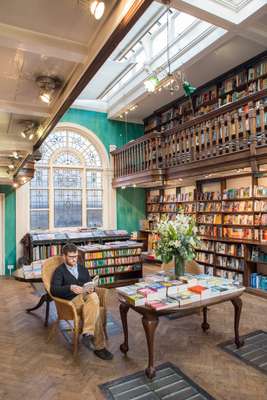

Time for one last cliffhanger. Just as the global book world began to ponder a bright 2016 the old adversary has opened a bricks-and-mortar bookshop in Seattle. Amazon may not have matched its US digital dominance in the rest of the world but its actions are talking points the world over. Brett Wolstencroft, manager of Daunt Books in Marylebone, London, is worried for the independent-bookshop revival in the US: “Publishing has only just begun to move back their way,” he says. Still, sales growth at Daunt has been as good lately as it has ever been in its 25-year history. Expansion is back on the table in 2016.

Wolstencroft provides a thoughtful epilogue: what if Amazon finally learns what it means to run a bookshop? It will have to provide trusted reviews by knowledgeable staff; curate a range of unusual editions; connect the right books on display; and stage community readings. No algorithm can explain why book fans travel from all over the world to visit Daunt. Forget 10 years from now: few readers will travel to Seattle to buy a bestseller from Amazon in 2016. Especially not when they can get the same experience online.

Notes: How bookshops should celebrate the written word

- Books can be beautiful so show them off handsomely; from the window to the maps section, display is king.

- Retail is about atmosphere as well as quality so pick your niche and exploit it.

- Throw a bash: signings, readings and talks work wonders for selling books.

- Choose your staff wisely: the book trade should employ readers with a keen eye on a sale. If a customer goes in looking lost they should walk out with a week’s worth of great finds.

- Staff need to choose wisely too: personal recommendations from bright employees are worth their weight in words.

- Encourage browsing but don’t go for free wi-fi; the Starbucks model is not a good look for a bookshop.

- Confidence is key; remember, you are not a charity shop.

- Scrap the bestsellers shelf: would you buy a scarf because everyone else was wearing it?

- Don’t sell anything else. You’re a bookshop – why are you selling Monopoly, batteries and umbrellas?

- Be local but not parochial. Celebrate your street but keep an eye on quality.