Expo / Greece

Reportage: Captains of industry

Despite the economic and refugee crises crashing onto Greece’s shores, there is one line of work keeping the country afloat. We drop anchor at the maritime school and naval academy educating those who will be serving the country for years to come by signing up to a life at sea.

On the picturesque island of Hydra, a two-hour ferry trip from Athens, tourists clamber off the catamaran that’s docking on the eastern side of the tiny harbour. Greece’s islands have survived on tourism, never more so than during the financial crisis that has battered the nation for half a decade. The images of beaches lapped by blue waters, the labyrinths of winding alleys and the sun-bleached ruins have made this nation a prime worldwide destination, regardless of competing images of protests, riots and seemingly endless elections.

But the islands also have a powerful maritime tradition that has spawned generations of capable, cool-headed sailors and shrewd ship-owners. Despite the crisis, Greek shipping-magnate families remain some of the most influential in the world.

Part of the reason can be found looming over the harbour where tourists disembark: the Tsamados Mansion is a three-storey 19th-century building housing one of the world’s oldest merchant marine academies, dating back to 1749. One of 11 maritime schools scattered across tiny Greek islands, it educates 140 mostly male students every year. With unemployment hitting Greek youths the hardest, naval academies are witnessing a revival; applications have increased tenfold in the space of a few years. “There aren’t any land jobs available and Greeks have traditionally turned to the sea as an escape during difficult times,” says Vasilis Stavropoulos, the academy’s director of studies. He estimates that about 80 per cent of students will end up with well-paid jobs.

The academy’s curriculum ranges from nautical sciences to meteorology and English. The students are no older than 24 and must complete two full semesters at sea. During their school breaks they wind down at nearby coffee shops. “The crisis has hit both land and sea but the sea has definitely not been as affected,” says Thisseas Tsioutsas, 18, who has only just moved to Hydra. Captain salaries can reach up to €10,000 a month, a phenomenal figure in a country where the average is no more than €1,000 per month. The amounts go some way towards compensating for the sacrifices of life at sea: six months to a year away from home.

“The salary is still too little,” says Thisseas. He hopes to end up as a ship-owner; the students around him giggle. “I hope you manage – and make sure to get us a job!” says 20-year-old Santa Spinokia, one of the few women attending the school. “Life at sea doesn’t dissuade me at all; I take it as a challenge,” she adds. Women were only admitted to maritime schools after 2007 but their progression to companies hasn’t been easy. “I try to forget that I’m different. I’ve always been fond of the sea and ships, and have always dreamt of doing this; no one can stop me. Hydra is among the best: organised, with excellent staff – and it’s a historic establishment.”

The antiques and sophisticated decor in the building attest to it: swords adorn walls, telescopes are encased in large wooden furniture and an old ship cannon is centrally placed on the chequered marble floors. Commanding officer Ioannis Kokios sits behind a wooden carved desk overlooking the sea, from where he runs the school. Above him hangs the icon of St Nicholas, patron of sailors, while leather-bound shipping volumes line his bookshelves. The room feels as if it has barely been touched since the school moved into this building in 1930.

“The sailing profession has resurfaced and due to unemployment the level of the students has improved; highly educated students now pick marine academies as their first choice,” says Kokios. While the rules have relaxed, the establishment is strictly administered. “Discipline is very important; if they’re going to lead tomorrow they also need to be led.” Students are expected to appear in class shaved, well groomed and with no earrings. Final-year students take daily shifts helping out with studies, supervision and hierarchy, which are key principles for life at sea.

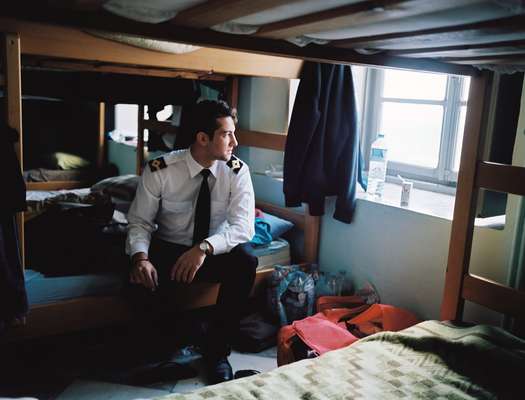

Not all of the students want a career at sea though. Sat in one of the dormitories is 21-year-old George Pandis. “This school shapes you for life, instilling discipline, ethics and a proper mentality,” he says. Above each of the entrances to the austere dormitories filled with wooden bunk beds and cupboards, notices read, “Greece isn’t land, it’s a sea embraced by land.”

Dotted around the school are other golden placards reminding them of the shipping benefactors who fixed the showers, bought the navigation PCs or overhauled their bedrooms. Yet despite the lack of funding, the school frequently distinguishes itself in the Lloyd’s List maritime and shipping-industry awards.

Ship-owners in Greece have been patrons for centuries. During the country’s war of independence many of them turned their vessels, which were already equipped with a small arsenal to fend off pirates, into warships. One was Andreas Vokos, nicknamed Miaoulis, from the Ottoman empire, a hero of Greece’s 1821 war of independence and a captain and corn trader who led the naval resistance. After the founding of the Greek state, Miaoulis encouraged the creation of a military naval academy. Today it’s found on the mainland in Athens, right at the end of Piraeus harbour, the country’s main port.

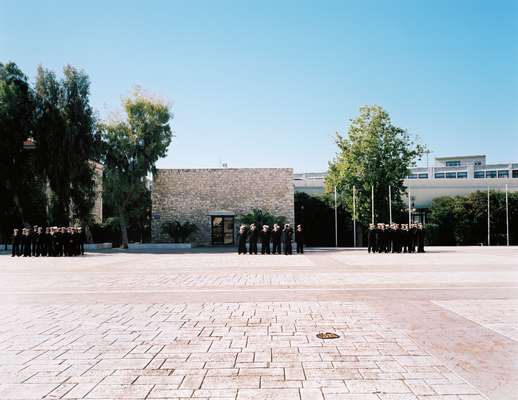

On a walk from the main stone building to the classrooms, cadets are seen jogging from their classes to have lunch, study or work-out. But they keep their senses on high alert, halting to attention whenever they stumble upon a superior, who more often than not will ignore them.

Running is pretty much what they’re doing from 06.20 until the end of their day at 22.30. In between runs they attend classes, eat four times a day, pray three times a day and go to the gym. Besides the love of the sea, patriotism is what appeals to these youngsters. “The criterion here is to protect your country and love it,” says Ilias Mouleas, 21, a final-year student.

Despite the financial crisis, Greece still spends 2.2 per cent of its GDP on defence; that’s joint second highest in Nato. “The expense is not very high considering our neighbourhood and its problems,” says rear admiral HN George Leventis. “This isn’t Belgium: we’re surrounded by countries with territorial claims to our land.” The academy’s museum includes a room dedicated to the fallen. The most recent victims are naval officers who died in 1996 during the ongoing Aegean dispute between Greece and neighbouring Turkey, a reminder of the enduring tensions.

At lunchtime the students are summoned to Eleftheria (Freedom) Square, located between the main building and the refectory. Perfectly aligned companies of cadets are quickly formed. Within minutes they disband for lunch in the shadow of aspen trees and against the backdrop of the glistening waves of the Aegean. Greek staples are laid out on the refectory’s large rectangular tables: tomato and feta salads, bread, pastitsio (Greek-style lasagna) and pears feed about 170 mouths. That figure is 30 per cent lower than it was before, thanks to the country’s economic woes. But smaller admission numbers mean stiff competition for a place. “The financial crisis has become an excuse for many but we’re showing we can do more if there’s will,” says Leventis.

Despite the variety of lessons on offer, staff here say that the Greeks’ comparative advantage is a focus on maritime skills and practical training. Despite the cuts, foreign students primarily from North Africa and the Middle East continue to move here for their studies.

Seydouna Hamza Amar, 23, is among the 29 foreigners attending the academy. He moved to Athens from Senegal in 2011 after completing his baccalaureate and already speaks fluent Greek. “I have no regrets about coming,” he says. “I feel more advanced than my friends studying in France. Not only on an academic level but I’m also proficient in maritime studies and more mature; the Amar who got here was different to the one speaking to you now.”

The islands and their maritime traditions are helping Greece through its recovery as they always have done, through good times and bad. And it seems a sailor’s adage from the lips of a Senegalese is useful advice for the debt-battered country. “It’s not because there’s bad weather that a ship will stop its course,” says Amar. “The navy teaches you patience and a will to never give up.”