Expo / Germany

Reportage: Fabric of society

The textile-and-clothing industry has always been integral to Europe’s economy. Despite Asia’s recent dominance, German looms and presses are still whirring away as tried-and-tested companies are brought back into the fold.

The noise is deafening. Twenty looms are running at full speed in the machine hall, reels clatter nearby as they frantically spin and a few metres further away thick strips of fabric are being pulled through a vat of dye. In this industrial setting the last things that come to mind are fluffy teddy bears and designer coats. And yet this is exactly the place to which both items can be traced back – at least in part. This is the factory of Webmanufaktur Steiff Schulte, a place where the German textile industry becomes noisily intelligible.

Textile manufacturing is one of the oldest industries in Europe; well before industrialisation it was an important pillar of the continent’s economy. In recent years, however, the sector has been battered. Globalisation has thrown what were once established structures into chaos and today most of the textiles handled worldwide come from Asia.

Germany is the exception. This nation of industry may well be better known for its expensive cars and Bavarian beers but, when you scrutinise global textile and fashion supply chains, you quickly realise the ubiquity of “Made in Germany” products. It’s highly likely that in any textile product – from the denim of an international jeans brand to the seat of a luxury SUV – the country’s technology and materials will be playing a crucial role.

Germany’s textile-and-clothing sector is the country’s second-biggest consumer-goods industry, directly behind grocery sales. It accounts for about 130,000 jobs and 1,400 companies, creating a turnover of about €30bn. Roughly two thirds of this is from consumer products but the rest is from business-to-business sales, such as to furniture makers and the car industry. While the competition from abroad is tough, the figures still make for happy reading. For the first six months of 2015, sector union Textil+Mode reported an increase in revenue of 1.5 per cent; this was in spite of reduced trade with Russian customers, who are so important for the export market.

Yet even though these are companies producing for the world market, the success of the most notable German firms is often founded on the fact that they have continued to manufacture in their home country. Our report focuses on three companies whose products almost everyone will have come across at some point – mostly, in all likelihood, without ever knowing it. These companies are different in terms of their structures and the products they manufacture but what unites them is their anchoring in their homeland.

So back we go, then, to the machine hall in the industrial town of Duisburg, and to Webmanufaktur Steiff Schulte. This is the company that supplies the fake fur for the famous Steiff teddy bears and has done so since 1901. In 2009 the firm was bought by the German toy maker, its top customer. Bernhard Wanning runs the factory, which employs 40 people working in the weaving, colouring and finishing departments, all found under one roof.

“One advantage is that we are fully integrated here,” says Wanning, who knows the company inside out. “We therefore have full control over the product and can respond with flexibility to a customer’s specific wishes.”

Just as well because about eight years ago the company was approached by Miuccia Prada with a very specific request. She was one of the first designers to recognise the potential of Steiff’s fake fur in the fashion industry. Prada took delivery of an order from the company in 2007, used the fabric in a runway collection that autumn and has since regularly included it in her designs. As the controversy surrounding genuine fur has continued and the demand for alternatives has risen, many names in the world of luxury fashion have come onboard: Marc Jacobs, Max Mara, Coach and Michael Kors, to name a few.

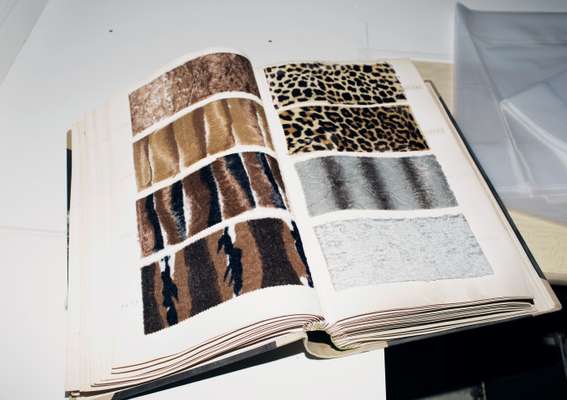

The production process at Steiff Schulte is painstaking and combines mechanised processes with manual techniques. The fabric is first made on 20 so-called “rapier” looms. It can then be dyed and given more than 20 finishes, many of which are done by hand. In order to achieve the perfect surface effect, as many as 20 different steps are necessary, including ironing, trimming (to get all the strands of fibre the same length), roughing up (to open the fibres and create density), drying, stretching and steaming. These processes must be done by hand to create a fur that looks as natural as possible. Finally, the finished material is run across a light table that allows rare irregularities to be spotted.

As the fashion industry is somewhat more volatile than the stable teddy-bear market, the pressure to innovate is immense and the business has had to adjust its structure. But at Steiff Schulte, innovation always goes in step with maintaining traditional techniques because it is the high level of handwork that turns out the colour tones and the consistent appearance of every fabric. As Wanning puts it, “Here experienced employees make all the difference.”

Looking at a Steiff teddy bear, what first catches the eye is not, however, its soft fur: it’s the trademark button in its ear. This quirky feature is also made in Germany – or more precisely, in Stolberg in the Rhineland. Here, for centuries Prym has successfully walked the tightrope between history and hi-tech innovation.

The roots of what is today William Prym Holding were laid down in1530 in Aachen by metal worker and goldsmith Wilhelm Prym. As such, Prym can claim to be the oldest industrial family-owned company in Germany. Although it is more than 450 years old, the greatest achievement in the firm’s history came in 1903 with the development of a new form of snap fastener, or popper. It contained a so-called “Doppel-S” spring that held the button in place. Today this type of button is still one of the company’s most important products, used in textile items around the world.

The firm’s headquarters in an industrial neighbourhood are found in tall brick-walled buildings akin to a fortress. The company is divided into three branches: Prym Consumer, making sewing and knitting accessories; Inovan, which makes parts for the automotive industry; and Prym Fashion, whose main product is fastening systems for B2B customers in the textile and clothing industries. There are 3,300 employees working in 60 countries but around a third of the workforce is here in Germany. And despite its orientation towards international markets, the company’s Stolberg headquarters play a vital role. The core product is still made here, as are the machines and tools that industry customers need to actually attach the fasteners to garments.

“The decisive factors in order to keep ahead of the competition are innovative products, consistency in the production process and short delivery times,” says Axel Wirthmüller, vice-president of operations at the Stolberg plant. Inconsistencies in quality and appearance are, he adds, virtually unthinkable in times of highly automated processes. But even here a skilled workforce is crucial to the brand’s success. “Details make all the difference,” says Rudolf Malmendier, who recently retired after working at the company for 45 years, latterly as product manager. “You really need to have a lot of experience in order to get the correct result at the end of the process.”

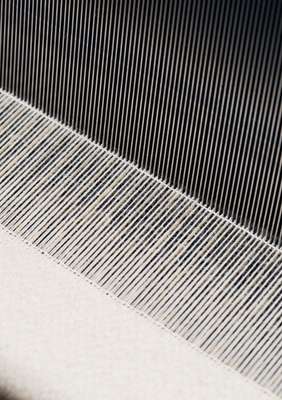

But back to the poppers. The first place where the fasteners begin to take shape in Stolberg is in the stamping room, found on the fourth floor of the factory. Here the individual building blocks of the button – mostly in brass – come flying out onto the conveyor belt of an industrial stamping machine. Up to 7,000 small metal rings spring out every minute from the yawning mouth of the stamp. These machines run 22 hours a day in two manned shifts of seven hours, plus a so-called “ghost shift” when they run all by themselves. Then, the surface of the buttons is treated and degreased in huge metal drums. Up to 10 tonnes of tiny metallic parts can be worked on every day.

While this is a highly mechanised process, the human eye and the long-time experience of the employees come into their own at the so-called “K-Point”, or the control point. Here the surface of the buttons is checked for the right colour and shine. Once the checker has let the goods go through they are then automatically transported to the warehouse. “It takes roughly three days from the raw material arriving here to the moment the buttons are finished and ready to be sent out,” says Wirthmüller.

Prym’s popper is a classic. Although the founding principles of the fastener have changed little during the past 100 years, new fashions mean that there is pressure to innovate. For instance, in the fitness-fashion branch of the industry, lightness is currently of paramount importance, meaning that new materials and slicker designs are in demand. Meanwhile, larger versions of the popper that can be sewn on to heavier garments such as cardigans and capes are currently experiencing a resurgence.

When a Prym product is fixed on to a garment using a cotton thread, it is likely that the thread itself will also be made by a German firm – and it is even more likely that it will be made by Amann & Söhne. The manufacturer is based in the sleepy town of Bönnigheim, about 40km north of Stuttgart on the Neckar River in the state of Baden-Württemberg. But the actual production takes place elsewhere, in the small Bavarian town of Augsburg.

Besides the plant in Augsburg, the company also has countless international premises and 1,800 employees. Even understanding the sheer size of the Amann operation is tricky. Globally the company has a production volume of one million kilometres of yarn every day; that’s enough to make two million suits.

The Amann yarns are not, however, only used in jackets and trousers. They are also put to use in textiles for the home, from furniture to embroidery, and in the automotive industry; they are, for instance, found in the seams of many air bags.

The Augsburg site is indispensable for all of these divisions. “All our innovations are developed in Augsburg and tested here for the first time,” says Barbara Binder, global marketing director at Amann. “We have only recently invested in equipment and employees for our R&D department here. We’re seeing a lot of potential in the area of functional applications of composite and smart textiles.”

The company is currently researching new possibilities of equipping clothing with conductive fibres that, when used in sports clothing for instance, can relay information on body temperature and heart rate. In the automotive industry and the construction of aeroplanes, meanwhile, the demand for lightness is high but stability and durability cannot be sacrificed.

“The distinction between purely technical textiles and fashion products is being eroded,” says Binder. Functionality, flexibility, lightness and longevity are the defining drivers in all areas of application; and in constantly new combinations. “But innovation requires time and money,” she adds. “For a Mittelstand firm such as Amann that means carefully choosing the projects in which we invest and, of course, proximity to the market in order to recognise trends.”

Even established players in the German textile industry are constantly facing immense challenges, from customers demanding new and innovative products to competitors snapping at their heels. But the signs are positive that the significance of Germany as the home of industry in the midst of a highly globalised supply chain can be maintained, even strengthened, in the years to come. A current study by the Boston Consulting Group entitled Apparel at a Crossroads: The End of Low-Cost-Country Sourcing predicts the waning of cheap manufacturing worldwide and demonstrates that rising costs and changing customer demands will necessitate completely new approaches and solutions in procurement and production.

Vast textile mills will not, of course, return from Asia to Europe overnight. But the future clearly lies in innovation through highly skilled engineering, smaller factories, close-to-market manufacturing and new, more intelligent forms of automation. It might not ever be visible on the catwalks of fashion shows around the world but this trend will be a key talking point in boardrooms and industrial parks across Europe. Anyone wanting to follow the rapid development of the clothing-and-textile industry would do well to consider the technology and products behind the garments – and keep the textile behemoth of Germany in their sights.