Global Affairs. Silver-set cities / Toyama

Ageing gracefully

How to care for an increasingly large ageing population is a question that faces every city. But those that answer it – as the city of Toyama has – by inviting seniors to live and interact in their centres are discovering far-reaching benefits.

If you were looking for a candidate to represent the image of “healthy ageing” then Eiichi Takeoka would fit the bill. The 90-year-old lives alone, rises early to prepare his packed lunch and then heads to work. He is the president of Takeoka Auto Craft, a mini-car company he started in 1989 and now runs with his son, Manabu. He eats well, exercises every morning and gets around in a senior-friendly vehicle of his own design (top speed: 33km/h). He has a monthly check-up at the local hospital but is otherwise in tip-top condition. His secret? “Discipline,” he says with a smile. “I learnt it in the navy.”

Takeoka lives in Toyama, an attractive city of 420,000 on the Sea of Japan. In a country that is now working on the assumption that 30 per cent of its population will be over 65 by 2025, Toyama – where 28 per cent are already seniors – is leading the march towards gerontocracy. Instead of giving in to a demographic inevitability, Toyama is confronting the dual challenges of ageing and depopulation head on. Over the course of the past 15 years, Toyama, which was sprawling and car-dependent, has been reinvented as a compact city. It now revolves around a cheap and accessible new public transport system designed to keep the elderly active and bring people of all ages into the centre.

The man responsible for the radical overhaul is mayor Masashi Mori. “Toyama was a continually expanding, motorised society, just like many other Japanese cities,” says Mori. “And yet the population was decreasing and ageing; we knew those people wouldn’t be able to use cars in the future. We realised we had to do three things: rebuild the transport system, subsidise people to move into the centre and bring facilities into the city.”

Toyama – which was linked to the bullet train network for the first time in spring 2015 – now has a quiet new light-rail transit system with lower floors, barrier-free platforms and discounts for elderly passengers travelling from the suburbs. Mori and his team have worked hard to make the centre more appealing using everything from flower baskets to a smart new museum and public library designed by architect Kengo Kuma. Seniors who visit city facilities with their grandchildren are offered free entry.

The point is to make the city centre a vibrant place to live and work. There are financial incentives for anyone who moves into it: subsidies of up to ¥500,000 (€4,300) to citizens who buy a house and up to ¥10,000 (€85) a month for renters.

Another pillar of Mori’s compact city policy is to look after the growing population of elderly people and keep them as active and healthy as possible so that they won’t need expensive medical care. A showpiece of the approach is the Kadokawa Independent Living Centre, a preventative health centre for seniors. On any given day of the week, dozens of active older people are joining in with group fitness classes in the pool or hot spa area (there is a natural hot spring 1,200 metres directly below). There is a steam room, sauna, studio and senior-friendly weights room; a doctor is on hand to monitor blood pressure and bone density.

“There was nothing like this in Japan,” says manager Kyoko Hamatani. “Our aim is for older people to stay at the same level of fitness or even improve. If they are stuck at home, their ability to walk decreases and they’re more likely to fall. This centre is about physical fitness but it also has a huge impact on mental health too: by coming here, people get out and meet friends.”

Now 250 people come to the centre, which opened in 2011, every day. Four buses offer door-to-door transport for those who can’t make it on their own. It has already paid dividends: health tests on regular users show that their physical abilities have been enhanced.

Toyama has produced another innovative facility in the form of Kono Yubi Tomare: a daycare centre where young and old, able-bodied and disabled are looked after together. Kayoko Souman, the nurse who started the enterprise in 1993, said it was a struggle to gain acceptance at first but today there are 1,400 such centres around Japan. On a sunny autumn afternoon the staff and their charges sing “Happy Birthday” to 84-year-old Tomie Tamamura. She is presented with a homemade card and cake is shared around.

“If you have only elderly people together, it can be very quiet,” says Souman. “Children change the dynamic of the room – they are energetic and talkative. Older people benefit from that. Children can learn things from older people too. They are loved and sometimes they’re told off. People they know might die and they learn to face that too.”

“We can’t do anything about ageing but we can do more to keep older people healthy and cheerful,” says Masashi Mori. “We’d like more seniors to move into the centre but if they don’t, we still want them to be able to get out and about on public transport and stay active.” Eiichi Takeoka’s mini cars, which are made at Takeoka’s workshop in Toyama, offer retirees an alternative mode of transport. With their low speed and super-light FRP bodies, they are designed for the elderly driver who only needs to make short trips.

Toyama’s radical approach to the issue of ageing has drawn interest from cities around Japan and beyond. It was designated a “Future City” by the Japanese government in 2011 and was picked for the UN’s “Sustainable Energy for All” initiative.

“Ageing is not just an issue for Japan and East Asia, it’s facing countries all over the world,” says Mori. In May the mayor visited Lisbon and heard from his counterpart there about the problems facing older people in his city. The issue might be more acute in Japan but the rest of the world is catching up.

In the richest nations about one in four people are over 60 – and the percentage is rising every year. The UN’s most recent World Population Ageing report warns that the figure for Japan is already one in three. Over the next 15 years the fastest growth in the elderly population will be in Latin America and the Caribbean, with a projected 71 per cent increase in the over-sixties, followed by Asia (66 per cent) and Africa (64 per cent).

According to the World Health Organisation (who), the number of people aged 60 or older will outnumber children under five by 2020; by 2050 there will be two billion people over 60 (up from 900 million in 2015). Western countries have had years to adapt to the new longevity; Brazil, China and India will only have 20 years to make the same level of adjustment. By 2050, China is projected to have 90.4 million over-eighties, the world’s largest population of this most elderly group (and quadruple the number in 2013).

With statistics like these it’s no wonder that countries are racing to get their policies for seniors in order. Causes and solutions might be specific to each region but it is clear that ageing is going to affect every corner of the globe. Governments in Asia are being increasingly proactive. Hong Kong – whose seniors are among the world’s longest living – has had an Elderly Commission since 1997 that advises the government on policies for its older population. Singapore is hurling s$3bn (€2bn) at the issue. Earlier this year the government announced its “Action Plan for Successful Ageing”: more than 70 initiatives for the elderly that range from installing slower traffic lights and therapeutic gardens to a National Silver Academy for 30,000 mature students.

Many cities are working to tackle an outdated urban model that resulted in unchecked sprawl and roads choked with traffic. This move towards compactness and energy efficiency – which is happening everywhere from Portland to Freiburg – would benefit all sectors of society: the elderly, the young and the growing number of people living on their own. Policies that aid the elderly, such as easy access to services and better public transport, are likely to be good for others too.

In the past, governments have tended to look at the elderly as a fiscal welfare problem; these days the approach is more holistic and the goal is a healthy, integrated (and valued) population of elderly people who might still be working, volunteering, teaching and studying. In the Helsinki neighbourhood of Lauttasaari the city has piloted a project to develop care services by talking to older residents and taking into account their lifestyles and wellbeing. The German city of Köln has come up with programmes that tackle the isolation of older people by encouraging multigenerational housing, community networks and the establishment of small shops in the city centre.

Some 332 cities and communities around the world have signed up to the who’s voluntary “Age-Friendly Cities” network, which started in 2010. Cities are required to offer concrete plans on how they will become more age-friendly and agree to monitor their results. “It must be a plan involving multiple stakeholders – not just one mode of transport, or just hospitals – working across different sectors,” says senior health adviser Alana Officer. “It’s not just about the elderly, it’s about people of all ages living in a socially cohesive community – bridging the gap between generations.”

The maturation of the world’s population can’t be halted but healthy old age is an achievable goal. The Max Planck Institute for the Biology of Ageing in Köln, founded in 2008, focuses its research on the causes and processes of ageing, its scientists scrutinising the reasons for longevity and finding ways to ameliorate age-related diseases. It turns out that lab research into the lifespan of worms and flies has human applications and the institute works with local clinicians and pharmaceutical companies to find real solutions to provide a better quality of life.

Dr Jane Barratt, secretary general of the Toronto-based International Federation on Ageing, says that older people have an increasingly important role to play. “With the whole world ageing we’re asking them to stay in the workforce. The world is changing its view on the elderly; they are not a burden to society. As long as they are healthy they can contribute both mentally and physically. They can work themselves or look after their grandchildren, allowing their children to work more.

“Smart nations and cities are adopting investment into keeping the elderly healthy, rather than investing in them remaining institutionalised and isolated,” adds Barratt. “A lot of this research, which started to gain momentum about 10 years ago, is about how to balance and combine different types of policies to maximise the intrinsic capacity of all generations.”

Even a light tweak to the local environment can make an impact. In the hilltop town of Gironella in Spain, architect Carles Enrich built a 24-metre outdoor lift that helped seniors in the steep historic centre go down the hill to where younger residents tend to live. “We are entering a period of needing to scale up the small-scale experiments that have been tested in these cities,” says Dr Barratt. “Evaluation of age-friendly cities and the results they are delivering will become very important.”

Toyama continues to draw interested visitors from all corners. When we visit Masashi Mori, the mayor had been playing saxophone (he does a fine rendition of “Misty”, by all accounts) for a group of visiting delegates from the World Bank the previous night. The following week he was preparing to welcome a large group of officials from Sweden. “Each city has to have its own approach,” he says. “We can provide hints and ideas but not results. The Toyama model has to be rebuilt to suit each place.”

Mori, who is toying with a fifth run at office in April, has many more plans, including safeguarding the city’s network of 79 local community centres and and pushing ahead with infrastructure investment to connect the bullet train, local train, tram and city-loop lines to make the city accessible without a car.

Moving to another city or even another country is not an attractive option; most seniors, wherever they are in the world, prefer to stay somewhere familiar. Toyama proves that point well. A survey showed that an astonishing 98 per cent of people born there in 1969 still live in the city. Some might have gone away for work or university but almost all come back. As Mori, the city’s most tireless advocate, says, “It’s just a very easy place to live.”

NOTES: Three places doing it well

As the elderly population increases, so will the need for a diverse range of specialised accommodation.

Bermondsey, London: Architecture firm Witherford Watson Mann designed a contemporary almshouse to provide independent accommodation for 90 residents. Spread over five floors, the building will counteract loneliness by featuring plenty of windows, street access, a central garden courtyard and shared facilities including a hair salon.

Graz: This care home by Dietger Wissounig Architekten shows the value of human scale. Buildings are divided into areas that house 15 residents and one carer in each to create a warm atmosphere; each cluster has its own shared living area. Sunlight, openness and greenery are key ingredients.

Lisbon: Security is an important feature at Alcabideche Social Complex, a retirement home development where architecture firm Guedes Cruz built a group of 52 cube units with white translucent roofs; if a tenant sounds the alarm, the roof will glow red.

NOTES: How we’d do it

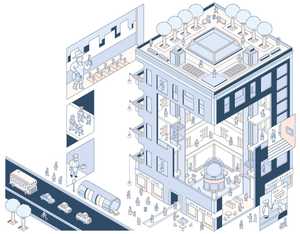

Located within the thrum of the city, our residential development promotes a social lifestyle for the silver set.

Well lit: Our five-storey building is flooded with natural light thanks to floor-to-ceiling windows.

Courtyard: The ground floor is alive with interaction. Here our friendly resident cat and dog mingle with inhabitants who shoot the breeze on high-backed chairs in a leafy courtyard.

Social Kitchen: The kitchen area makes for a focal point for residents to eat and cook together. Here they host culinary classes for the neighbourhood where old family recipes and traditional dishes are passed on to a younger audience.

Café and Deli: In the kitchen’s adjoining public café and deli (where room-service orders are delivered via an electric pulley system) residents can earn a bit of pocket money dishing up a menu they’ve helped to inspire.

Transitions: A handsome ThyssenKrupp lift leads to the rooftop farm. Moving between storeys is well planned, with shock-absorbing cork-floored stairs for fitness and safety.

Upper floors: Inside, smart private living spaces span the upper floors. There are also rooms reserved for family visitors on each floor.

Rooftop: Here planters allow gardening across various heights, meaning the space is alive with flora and fauna year round. There's room on the sunny roof for brisk jogs and morning tai chi.