Times of India / New Delhi

The big news

Covering everything from entertainment and spirituality to politics and crime across a staggering 56 daily editions, the ‘Times of India’ is the most widely circulated English language newspaper in the world. Read all about it.

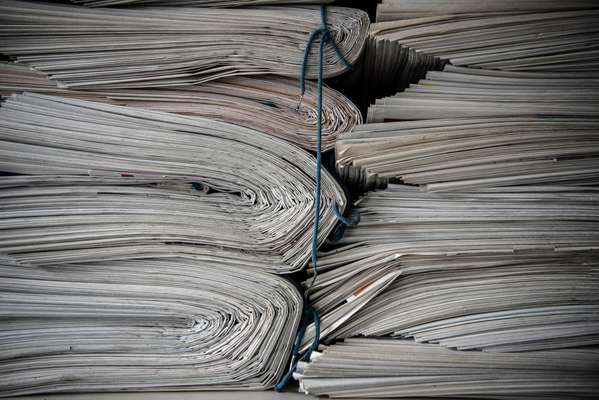

It’s 06.00 and Ram Lakhan jostles for position among the other delivery men as bundles of newspapers are dropped from the backs of the Times of India’s trucks onto a road in New Delhi. He now has less than two hours to race through the narrow streets and up and down the apartment-block stairwells of his patch, a middle-class neighbourhood, to ensure that his customers get their paper in time to read with their morning tea. He’s one of 30,000 deliverymen across the country who are a vital part of the machinery that has helped the Times of India (toi) retain its title as the most widely circulated English language newspaper in the world.

An hour later, another group of the newspaper’s early birds – crime reporters based in more than 50 Indian cities – begin their morning calls to police stations, finding out what went down in the dark of night. One of New Delhi’s three crime reporters is Somreet Bhattacharya and this morning – as every morning – he has spent an hour talking to groggy night-shift officers before he heads out to follow up on leads and catch up with investigators in person.

“It’s not always easy waking up to news of suicides and murders, being on the phone all day, but it’s the job,” says Bhattacharya, who has been at the paper for seven years and has broken stories about a national kidney-extraction racket and the murder of a politician’s son.

Back in the newsroom he sits down to start filing the five to seven stories that he’s expected to deliver every day. This is also the point in the morning when the political and law reporters, gearing up to stalk the halls of government and court houses, are heading off on their daily hunt for news.

But it’s not just politics and crime that will fill the 30-plus pages of the Times of India today. There’s a city reporter writing a story revealing that New Delhi’s electric rickshaws, meant to decrease pollution levels, are actually running on cheap, dirty fuel. Another reporter is assessing whether a massive hike in traffic fines is taming India’s notoriously unruly roads.

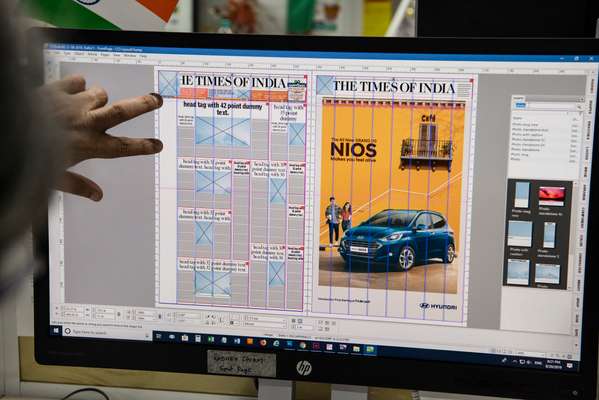

Unlike many of the country’s politics-heavy newspapers, the TOI has a more popular approach to news, offering stories that it hopes will appeal to India’s growing middle class. Much like India itself, the paper is crowded and colourful, with headlines in different fonts, bright sidebars, photos everywhere and lots of huge adverts. Very lively.

It’s a far cry from the staid, colonial paper it once was. Originally called the Bombay Times, it was founded in 1838 to inform the British ruling class and business elite. But as India has changed, so has the TOI, often called the “masthead of India”. After the British left in 1947, the paper championed the nation’s early development and socialist values. But when the markets began to liberalise in the 1990s and a more consumerist middle class emerged – people with interests beyond activism and politics – it gained a different audience. Its cultural reference points no longer looked westward but were proudly rooted in homegrown entertainment, food and fashion.

The owners of the paper today are two business-savvy brothers, the third generation of their family to be at the helm of a company still known formally by its old English title: Bennett, Coleman & Co. They have capitalised on India’s changing demographics and turned the firm into a media empire. The younger and more public of the brothers, Vineet Jain, is a 53-year-old whose quirky specs and boyish smile belie the sharp-shooting businessman beneath.

“The paper used to be really thin: 12 pages,” says Jain. “Now it’s three to four times that, including supplements, as we’ve dramatically deepened our coverage with more news, more data, graphics and perspective.” Jain is managing director of the firm, which also owns 13 other publications, 12 TV stations, 76 radio stations and a fledgling university.

Sitting on the ninth floor of one of the company’s many buildings, he smiles proudly as he likens the TOI to the original tasting plate of Indian dishes. “The paper is like a thali, a buffet of India. We offer the entire spectrum, from politics and crime to fashion, sports and spirituality.”

But being in step with its readers (the paper puts its daily print circulation at 4.2 million, which continues to grow) is not simple in a country with a vast mix of cultures, languages, religions and, at times, contradictions. The paper puts out a staggering 56 editions every day, with five to seven pages of “hyper-local” news in each one.

This mammoth task of publishing so many editions is not just about giving readers a bespoke product but also driven by the lure of tapping regional businesses, which would not be able to afford ad space in a national paper. “India’s smaller tier-two cities are expanding and new wealth is being created,” says Jain. “Literacy is also rising. We want to cater to this audience.”

By the afternoon the senior editorial team begins its day, arriving at the paper’s main newsroom in New Delhi, near the seat of government, in a utilitarian building owned by The Indian Express. This drab base is temporary: a fire destroyed TOI’s editorial headquarters in 2017 and a new building is being erected.

Three people gather around the desk of Shankar Raghuraman, a softly spoken senior editor who runs a small and earnest team of data-crunchers. Their attention flits from various spreadsheets they’ve mined from government, corporate and NGO databanks as they work on uncovering stories buried in the data.

Take, for example, the paper’s recent “lost votes” stories. The team exposed India’s anachronism of only letting people vote from the place they are registered in, without any postal vote as an alternative. After running the numbers for the previous national election, the team found that an astonishing 280 million people – a third of the electorate – were not able to cast a vote in the ballot. For weeks leading up to May’s general election, the paper ran profiles of “lost voters” and graphics decoding the numbers.

This statistical storytelling is so popular with readers that it regularly features on the inside of the paper’s innovative “front flap”: a vertical half page that sits on top of the front page. This week the team is looking at the data on school lunches, digging into everything from nutritional value to how much money is set aside to pay for them. They have found that many states don’t issue enough funds to cover the cost of a healthy lunch.

The political editor Rajeev Deshpande says that besides covering the horse-trading of India’s coalition government, he must also surrender column inches to other concerns, such as education and gay rights. “The paper tries to catch these moments, moving away from a world in which we’re just looking at parliament and policy.”

At 18.30, 19 senior editors enter the long conference room that’s flanked by large video screens showing the group’s news and business TV channels. Printouts of dozens of stories from different departments and regions are looked over while everyone waits for editor in chief Jaideep Bose to dial in to the meeting from the TOI’s original HQ in Mumbai. Much like Charlie in the 1970s TV show Charlie’s Angels, Bose is just a voice, avuncular but commanding, and everyone leans in when he offers his opinion as to the worthiness of a story.

During the meeting, the front-page editor uses pen and paper to draw and redraw the front page, which can have as many as eight columns of text carrying up to 20 stories, covering everything from the situation in Kashmir to the state of coral reefs. Bose does not lead the meeting but shepherds it with the grace and authority of someone respected. When we later visit the Mumbai newsroom he declines to be quoted, preferring, he says, for his work to speak for him and his editors to take the limelight.

Unlike many of the Indian newspapers losing readers to digital platforms that deliver content to smartphone users, the TOI has seen an upsurge in its print circulation. Executive editor Diwakar Asthana puts it down to the paper’s centrist and populist approach. “We get attacked by everyone, whether it’s the opposition or the government, BJP or Congress – whether it’s left-wing or right-wing. That shows we’re doing something right. We don’t pontificate as much as other Indian papers. We’re not preachy. We believe we don’t have to torment our reader every morning.”

Asthana points to a more frivolous recent story about a young man who pushed his BMW into a river out of anger after his father refused to buy him a Jaguar. “More cerebral papers wouldn’t want to waste space on such a story.”

Such is the premium that the paper places on lifestyle and entertainment news that it publishes a daily 12-page supplement on such topics – and that can double in the festive season. It also offers “hyper local” content with 46 city editions. Its newsroom is across town in Delhi’s “film city” and its editor, Anshul Chaturvedi, reports directly to managing director Jain. “We handle all the stories that happen in people’s supplementary time,” says Chaturvedi. “Everything they do when they clock off from work is what we report on. And our casual tone and language reflect that.”

The supplement’s special Delhi correspondent, Divya Kaushik, has spent the day writing a consumer guide to spotting sketchy massage parlours. However, by the evening she is reporting on a fashion show that’s featuring young designers, with a special appearance from Miss India.

Back in newsrooms across the country, after a strictly vegetarian buffet is served, only the sound of concentration (and the occasional order barked across computers) can be heard as the midnight publishing deadline looms. The last of the seniors to leave is front-page editor Vikas Singh. “I try to unwind but I stay awake next to my phone for another two hours. Just in case.”

Then it’s over to the dozens of printing presses up and down the country. While they run all day to produce the group’s other publications, they now whirr only for the flagship TOI, heralding another day in India.

India’s print-digital news diet:

News consumers in India have long bucked the global trend in their preference for old-fashioned ink on paper. But as 610 million Indians now have smartphones, (a number expected to nearly double by 2024) there is a steady move from print to digital. According to TOI front-page editor Vikas Singh, research shows that readers use digital throughout the day, while the newspaper is reserved for breakfast and leisure time. That’s when readers can linger over analysis pieces, editorials and features, usually while sipping some masala tea. “That’s the ‘tea’ in the TOI,” says Singh, smiling.

TOI is the largest English-language newspaper in India but there are local language papers with higher numbers. See right for the top five, based on circulation in the second half of 2018.

India's top sellers:

4.32

million

Dainik Bhaskar

Language: Hindi

3.41

million

Dainik Jagran

Language: Hindi

3.03

million

Times of India

Language: English

(4.2 million if including discounted distributions)

2.37

million

Malayala Manorama

Language: Malayalam

2.07

million

Amar Ujala

Language: Hindi

Delhi office

Meet the editors

Shankar Raghuraman

Senior editor, Times Insight Group

A former business journalist, now in charge of the TOI’s data-mining team, dissecting everything from politics to cricket with fastidious glee.

Neelam Raaj

Editor, Sunday Times

Makes sure the news gets more depth and analysis in the weekend papers. Married to a journalist at another paper – she’s glad hers is number one.

Vikas Singh

Front-page editor

The last editor to leave the building and doesn’t get to bed till after 02.00. When he’s not catching up on sleep he writes novels in his spare time.

Subhendu Mukherjee

City editor for Delhi

A harmonica player who enjoys being outraged at how politicians promise much but deliver little. Loves Delhi, even though his family is from Bengal.

Rajeev Deshpande

Political editor

Covers India’s dance with democracy. Having grown up when there were just two kinds of chocolate bars in India, he enjoys charting the nation’s growth.

Diwakar Asthana

Executive editor

Says the TOI succeeds because it’s not elitist. Likes it when it pushes social norms, whether women’s rights, gay issues or fighting for better nightlife.