Style cities / Global

To the letter

Montréal, Melbourne and Madrid are – in their own distinct ways – each blazing a trail when it comes to establishing (or reviving) themselves among fashion’s most sought-after cities.

1.

Montréal

Cool customers

In his office on the top floor of a building in downtown Montréal, Alan Herscovici, executive vice-president of the Fur Council of Canada, is spreading the word: fur should be worn again. “People must use natural resources and fur is part of it,” he says.

As you’d probably expect for such a chilly clime, the fashion industry in Montréal was long dominated by the fur industry. A huge Jewish population from Eastern Europe settled in the city before the First World War, bringing with them skills for making fur garments and helping define the bustling manufacturing industry. However anti-fur activists and intense Chinese production slowly ruined the business. And Montréalers’ lifestyles have changed: they bought cars and now spend less time in the cold. When they do, they wear technical outerwear jackets made more often than not in Asia. However, in Chabanel, the small fur industry’s home, some are working hard to reinvent what their forefathers built and a bunch of great creative young entrepreneurs are revisiting the fashion business – with a conscience.

Fur has had to find another life. In small touches and accessories, on hoods, gloves and shoes, fur is still tolerated. Brands such as Canadian Hat, ABC Fur Hats Manufacturing and Luna Furs are proof that fur is still flourishing in Montréal. Many designers here, including Harricana and Rachel F, have decided to use only recycled fur in their collections. “We recuperate fur coats that are no longer being worn and dissect them in order to reincarnate them as a variety of accessories,” says Rachel Fortin in her workshop at Hochelaga-Maisonneuve. But it’s not just fur. Also in Chabanel, on the ground floor of his family’s garment and wholesale company, Brandon Svarc runs Tate + Yoko. He is one of many young dedicated designers committed to reviving the broader manufacturing business in Montréal. “In the 1980s and 1990s, 95 per cent of the products sold in Canada were manufactured in Canada,” says Svarc. Now it’s the opposite: 5 per cent is made in Canada and 95 per cent is imported.”

“I had this amazing base, I had the knowledge, the space, the manufacturing, we kept the building, I had to do something really crazy, really creative.” And that’s what he did with his denim brand Naked & Famous, made with Japanese fabric but sewn in Montréal. “I’ll close the brand down before we move our production, that’s the promise. That is the rule.” Brandon’s father Sonni – who is now helping his son with the business’s finances and distribution – is confident: “Although it will never be like in the 1970s again, there will be a renaissance in the ‘Made in Canada’ promotion. There are few other entrepreneurs like Brandon who have great ideas.”

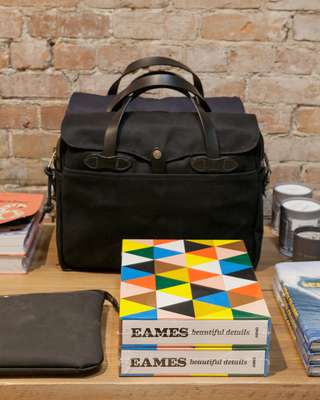

Despite the efforts of Montréal City, which injected ca$17m (€12m) to transform the Chabanel area into the city’s very own Meatpacking District, the dream never came true, although other little neighbourhoods have become fashion hotspots. The rich, residential West Mount has become the place to be thanks to Byron and Dexter Peart, twin brothers and co-founders of Want Les Essentiels de la Vie, a cult high-end accessories label. Mile End, originally known for its concentration of Italian, Greek and Jewish communities, has became a mini Brooklyn. Many hipsters have opened small shops selling well-made clothes and serving good coffee. They’ll even trim your beard if you ask nicely. “Merci thank you,” as they say in Québec.

2.

Melbourne

Collaborative creativity

Australia’s second city is built around good taste and entrepreneurial drive and that goes for its fashion community, too. A vibrant mix of designers and manufacturers is harnessing a collaborative spirit and defying a wider industry downturn.

“We’ve got something special here in Melbourne,” says Courtney Holm, a menswear designer and founder of Menske, a popular quarterly event bringing together the city’s best artisans and designers. “We are passionate about our industry and there is a fearless spirit of innovating here that sees Melbourne designers taking a more daring and conceptual approach to fashion. We also have the openness and opportunity to learn from other designers, which doesn’t tend to happen in other Australian cities.” Holm adds that local designers are striving to keep a once-buoyant manufacturing industry alive, while a “Made in Melbourne” tag remains a powerful selling point for top-tier labels.

Nobody Denim is one such company, a family-owned operation producing premium jeans from a busy factory in Melbourne’s north. “My business used to stone-wash 18,000 pairs of jeans a week for fashion businesses in Melbourne,” says Jim Condilis, whose denim laundering company was the inspiration for Nobody Denim. The label was launched by his two sons Nick and John in 1999 with the help of his facilities; the heritage and quality of Australian manufacturing is one of its key assets. Nobody Denim’s business model falls into line with a broader ideal among Melbourne’s creative community to build brands that are about genuine brand stories. So says Graeme Lewsey, ceo of Virgin Australia Melbourne Fashion Festival. It’s the nation’s largest consumer fashion festival and connects citizens with the country’s most talented designers.

“There is a strong passion from customers here for local luxury,” says Lewsey. “A desire for beautiful, unique pieces that might only be possible to find in one local designer’s studio is something that can’t be denied as a great movement in Melbourne. There is also a real sense of Australia’s creative industries being celebrated overseas and there is a strong energy around contemporary Australian design and the idea of local luxury is an intrinsic part of this.”

While small labels across the globe have felt the pinch as an evolving industry has squeezed consumer-spending habits in disparate directions, Melbourne brands take a brazen attitude to the business. Richard Bell, co-founder of Threebyone, says his denim company was built purely around passion.

He adds that Melbourne labels both young and old tend to approach business with an optimistic vigour. “Whether it’s in coffee, hospitality or fashion, people buy into things for the right reasons – and that is around passion, knowledge and consideration.”

This passion echoes across Melbourne’s independent retail assembly, which is both surprisingly sophisticated and edgy. The tasteful tailoring of Oscar Hunt on the city’s famous Hardware Lane has allowed it to significantly scale up business in four years, and the conceptually daring fashion spaces of Dust and Sneakerboy have both earned cult followings. Affordable studio space in the inner city’s further reaches also allows emerging designers to set up shop at relatively low costs. Strateas Carlucci is an award-winning label regarded as one of Australia’s best prospects in the global luxury-fashion sector. Based in a former hosiery factory in East Brunswick, co-founder Mario-Luca Carlucci says the essence of Melbourne remains integral to the brand despite 75 per cent of its sales being overseas. “There is so much happening around us in the art, music and food scenes that the creative energy becomes the best sounding board for our label,” he says.

3.

Madrid

Resilient resplendence

The Spanish capital has long been a beacon of opportunity for the country’s creatives. Following decades of immigration, the city has emerged as a pan-Iberian melting pot and, despite the economic challenges, this diversity and openness is underwriting a fresh wave of fortune in the fashion sector.

Along a tree-lined street of Madrid’s Chamberí district, the red façade of Leyre Valiente’s new showroom and concept store is a bright symbol of this change. After cutting her teeth working for Alexander McQueen in London, the 29-year-old designer was enticed back to her home city by local luxury giant Loewe but is now building up her own label. Valiente represents a growing sense of optimism among the city’s young designers, who are finding inventive ways to carve out their own niche despite the economic malaise. Encouraged by lower rents, she opened her combined retail/studio space a few months ago to showcase her couture creations.

“Small-scale tailors are increasingly willing to work with new designers, particularly as middle-sized brands have decreased production,” she says. It’s good news for the designer who keeps busy with side projects, such as designing the staff uniform for the city’s iconic Callao cinema as well as preparing a new runway show following an invite from Warsaw fashion week.

Squeezed between Paris and New York on the fashion-week calendar, the local Madrid edition may struggle to attract international faces on the front row but organisers have concentrated their efforts on creating a platform for local labels instead. “We’ve strengthened corporate sponsorship deals in order to reduce cost pressures on local designers,” says fashion week director Leonor Pérez-Pita. Designers are supplied with staples such as models and make-up professionals, reducing the cost of a runway show to four figures rather than the six-figure sum often required for one of the major fashion capitals.

“It’s definitely a big help,” says David Delfín from his upgraded showroom in the Chueca district. “But the downturn has obliged Spanish designers to adapt even further to seek out creative new formulas.” Delfín believes difficult times on the domestic front “have awakened the imagination”. It’s paving the way for a more collaborative spirit, with designers in the capital often best placed to take advantage of new opportunities.

Originally from Málaga, Delfín today divides his time between his collection, designing the costumes for an upcoming Spanish National Dance Company production of Carmen, the odd Pedro Almodóvar film and a range of bathroom wares for the Santander-based Bathco.

Loewe’s opening of a new marroquinería (leather goods) school in 2013 is also attracting young skilled professionals to the capital. The luxury label aims to replenish the ranks of its ageing artisans, providing 60 per cent of graduates with positions in production and creating 150 jobs in the process. It bodes well for smaller players such as porcelain jewellery brand Andrés Gallardo, which sources artisans from Valencia and Portugal but is constantly on the hunt for talent closer to home. Starting as a two-person operation in 2011, they now oversee a team of five producing handcrafted pieces of which 80 per cent are sold abroad. “Cheap living costs in Madrid definitely helped us get on our feet,” says co-founder Marina Casal de Miguel.

“There’s a generational change occurring in the city,” says designer Manuel García who, alongside David García, comprises menswear label Garcia Madrid. Their classic yet colourful label was one of the first to associate itself with Madrid and they recently inaugurated their third store in the city and another in Chile. “Everyone from fashion editors to designers and customers is looking to support positive local stories,” says David. “This groundswell of support and change in local attitudes is fuelling newfound hope in the industry.”