Media / Italy

Hot off the press

In Italy’s crowded media landscape, two new national newspapers – and one youthful stalwart – are playing against type to prove that print can still be a powerful and popular medium for journalists and public alike.

the public-service paper

Linkiesta

Milan

When will print disappear? Never, according to Christian Rocca, editor in chief of Linkiesta, a popular Milan-based politics and current affairs website that is now publishing print issues. Despite pandemic-induced advertising losses making the business tougher than ever, “launching in print still means authority, especially in Italy,” says Rocca. Most importantly, it can work.

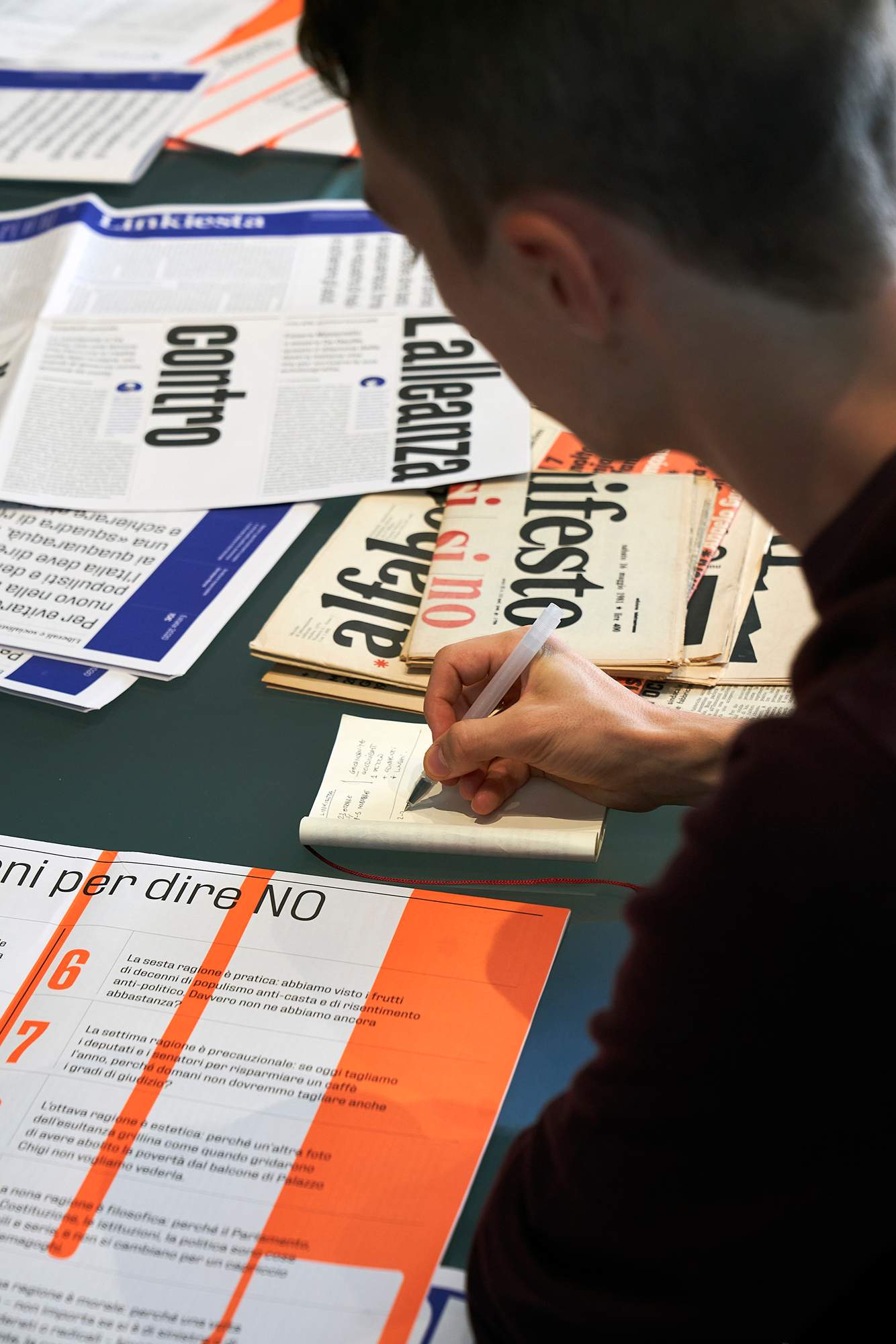

1970s design inspiration

Backed by a collective of 40 small investors when it was founded in 2011, Linkiesta skipped corporate shareholders to place decisions in the hands of its editorial team. About 20 backers remain, involved because they “believe in journalism as a public service”. Since taking over as editor last year, Rocca has had carte blanche to rethink Linkiesta’s role. Whereas many liberal-leaning newspapers have gone out of their way to prove that they’re not only aimed at a metropolitan audience, Rocca hasn’t been afraid (or ashamed) to aim at that very demographic, repositioning Linkiesta as “an elite publication for intellectuals”. He’s pulled in prestigious journalists, published extended think pieces and overseen an attention-grabbing look for the paper.

Business editor Lidia Baratta

Alessandra di Canossa, editorial secretary

The editorial team reconvened in September in the sleek archive building of Critica Sociale, a storied socialist newspaper whose vintage editions helped to inspire the striking aesthetic of Linkiesta’s print issues. “For a newspaper to make sense, it needs to have a unique spirit and be a beautiful object,” says Rocca. Despite its design influences, the title’s perspective is not socialist but, as Rocca describes it, “globalist, pro-EU and anti-populist”. Examples of its content include a study of Italy’s long-ignored colonial history and a list of reasons to vote against a recent decision to cut the size of the country’s parliament. Although Linkiesta’s subscription-free site updates daily, the print edition is only published “when we have something specific to say,” says Rocca.

“Launching in print still means authority, especially in Italy”

Today, Linkiesta draws much of its funding from a “friends club” comprising about 500 readers who have each offered between €120 and €1,200 a year, “with no other benefit than to support us”. The business is set to grow as the title racks up further funds from its new events club, live festivals and its work as a content agency.

Ultimately, Rocca believes that what sets the newspaper apart from its competitors is its attitude towards participating in public discourse. “Italian media is always reaching out to the worst of our nature,” he says. “What’s missing is something like Linkiesta, which calls us to the best of our character and our society.”

linkiesta.it

the ambitious start-up

Domani

Rome

At Domani’s Rome offices it’s time for the 10.30 editorial meeting. Softly spoken editor in chief Stefano Feltri addresses the dozen journalists present. The atmosphere is calm even though the team has a new national daily newspaper to send to print by 19.30. “It’s vital that we get this right,” says Feltri before opening up the conversation to the room.

It’s September and this is only Domani’s second week. The paper is the latest title to join the crowded Italian newsstand. Brainchild of leftist industrialist and media mogul Carlo de Benedetti, the newspaper – with its 26 full-time staff – is an attempt to revive independent, socially progressive, high-quality journalism in the country. It’s not surprising that De Benedetti called upon 36-year-old Feltri to help. As one of the founders of influential investigative title Il Fatto Quotidiano, he has a formidable reputation. “That experience means knowing all the mistakes that we made,” says Feltri. “I know that it is much more difficult to evolve and change a newspaper than it is to start one from scratch.

“It is more difficult to evolve and change a newspaper than it is to start one from scratch”

Holding a copy of the latest Berliner-format edition of Domani (“Tomorrow” in Italian), Feltri is visibly proud of the venture. Whereas many other Italian papers focus largely on domestic affairs, Domani takes a broader view. Feltri believes that his readers are hungry for something different. “Every issue, we try to have a feature related to the climate crisis and to inequality,” he says. Feltri also points towards a roughly fifty-fifty split in the male-to-female ratio of the editorial floor.

Domani’s fresh approach extends to all aspects of its production. Graphic design, for instance, was initially commissioned to an external agency but is now in the hands of editors who follow a series of pre-made templates. Rather than hiring designers, Domani is investing in positions such as a data editor, the first of whom is Filippo Teoldi, who relocated from New York to work here.

With a young, cream-of-the-crop editorial team behind him, Feltri is confident about the vision he’s creating. He believes that the paper’s predecessors and rivals are stale and often out of touch. “I don’t think most people understand what journalists are talking about,” he says. Tomorrow, it seems, there will be important, and well-written, issues to discuss.

editorialedomani.it

the zingy daily

Il Foglio

Rome

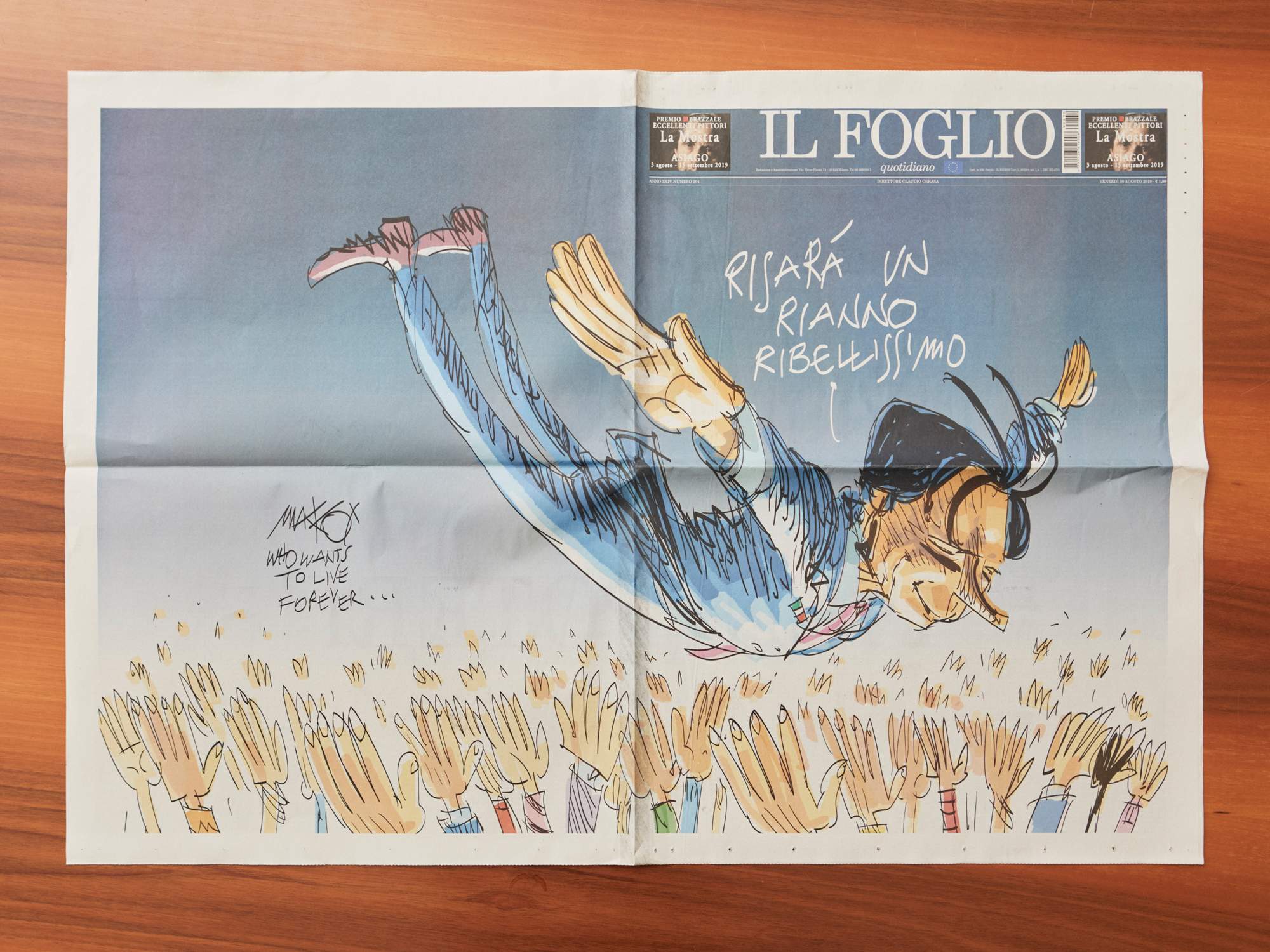

There can’t be many editors who would describe their typical reader as having the potential to be “a bit of a pain in the arse”. Yet that is how Claudio Cerasa puts it. At 38 he’s young to be editor in chief of a major national newspaper. But as he sits in his Rome office, the boss of Il Foglio is merely pointing out that, generally, those who buy his svelte, text-heavy broadsheet tend to have a certain reputation.

“There’s a feeling that you already know what kind of person they’re going to be,” he says. Specifically: serious, although not overly so; bookish with a wry sense of wit; “a bit of a nerd but also sort of cool”. Like its typical reader, Cerasa’s newspaper – founded in 1996 as a centre-right, opinion and political analysis-led daily – straddles many cultural boundaries.

“We are choosing to direct our news agenda rather than to digest”

The daily editorial meeting takes place at 11.30 at Il Foglio’s Via del Tritone offices, inside an elegant, art nouveau building. “It’s the magic moment of the day,” he says. Despite the 20-member editorial staff currently coming into the office on rotation, face-to-face meetings are something Cerasa is determined to maintain. “I’m not here to simply gather ideas,” he says. “Only by tackling and comparing stories all together are ideas born.”

Another feature that helps Il Foglio steer its editorial path is that the front page is put together in the morning, not in the evening, as is the norm with dailies. This means that Cerasa and his team set the agenda for the day and are not beholden to reporting developments, no matter how big the news might be. “We are choosing to direct rather than to digest,” he says. Cerasa admits that this path is not always easy but in many ways the strategy puts Il Foglio in an advantageous position by turning it into what Cerasa calls “a second read” – perused after a bigger news daily. It gives the paper the scope to dig deeper into a few choice topics and often with the kind of long-form writing that is hard to find elsewhere.

The title’s editorial line covers a broad church but Cerasa is clear on what is and is not acceptable. “We are against political correctness,” he says. “Although not when the war against political correctness is in any way linked to political extremism.”

Il Foglio’s journalistic style is working: daily print sales from kiosks rose during Italy’s lockdown. Average daily distribution stands at about 29,000 copies and unique website visits are between 200,000 and 1.5 million a day. This newspaper’s editorial position might be peculiar but it is timely. “The big divergence is no longer between left and right,” says Cerasa. “It is between being open and being closed.”

ilfoglio.it

Photographers: James Mollison, Luigi Fiano