Espionage / Global

How to be a modern spy

As digital footprints have become easier to follow, the espionage game has changed. We track where it’s heading.

Anybody reading this article is probably able to find out more about individuals, governments, corporations and countries than the most diligent and pervasive intelligence agency of just 40 years ago could have dreamed of. Suppose, as recently as the mid-1980s, you were a lowly agent of a Nato intelligence service instructed to discover the top speed of a particular Russian-built armoured personnel carrier – the btr-80, say. Disinterring this single mundane fact might have taken weeks of patient espionage. It can now be gleaned in seconds by any clown with a laptop – it’s 85km/h, give or take – and so can a great deal else.

“We shouldn’t give up on the old style completely,” says Yossi Kuperwasser, former head of the research division of the Israel Defence Forces. “But the way we approach this changes dramatically. You can reach everybody all the time. You can see a lot of things happening. Maybe in the past you needed a human source to understand the relationship between Bashar al-Assad and his family member Rami Makhlouf. Today they fight openly. But you can understand it better if you have someone standing in between them.”

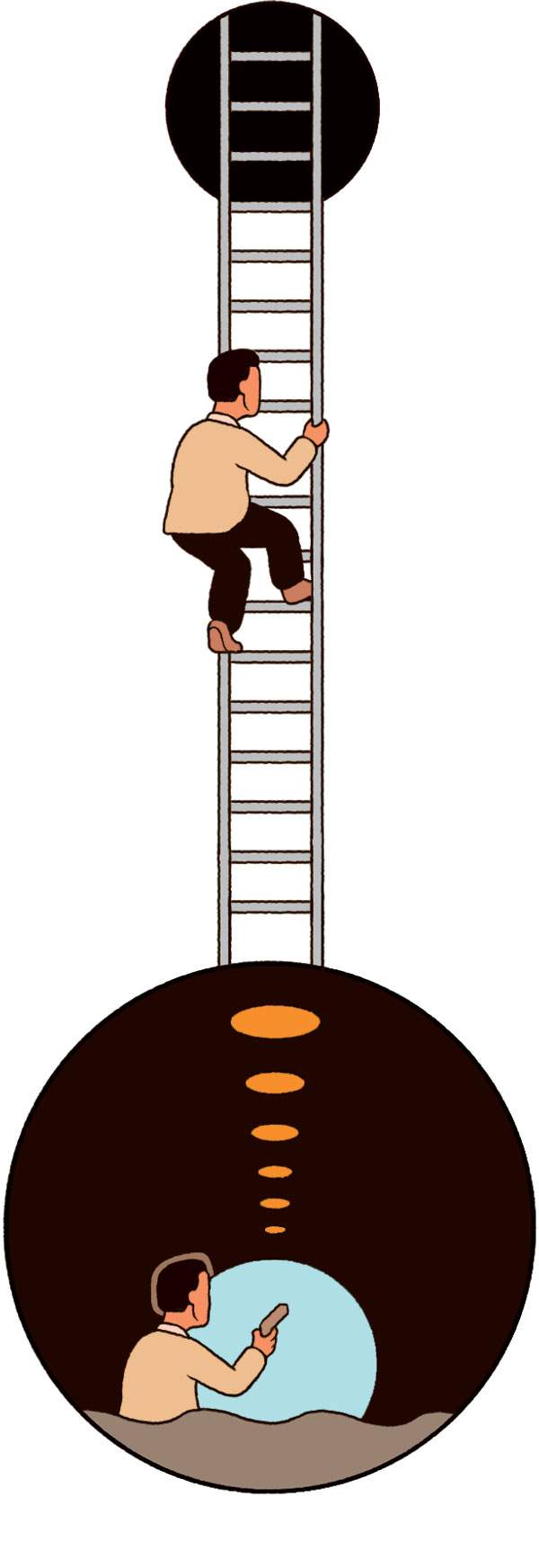

While the online realm has clearly made finding out some stuff much easier, it has made the mechanics of finding out other stuff – of actually getting between or, indeed, next to targets – much more difficult. The difficulty with almost everybody knowing almost everything is that almost everybody knows almost everything.

“The physical interaction between two people – an intelligence officer and a source of information – I’m not prepared to consign that to the dustbin of history,” says Doug H Wise, former deputy director of the US Defence Intelligence Agency and, prior to that, a long-serving cia officer with extensive experience as a field operator. “But it’s going to be nearly impossible to do two things: to remain anonymous for any period of time and to travel undetected.”

It’s not just that everyone now leaves a trail of digital breadcrumbs wherever they go and whatever they do; it’s that this is now so fundamental a fact of life that few actions arouse suspicions more than going quiet. One of the clues that led American analysts to Osama bin Laden’s compound in Abbottabad in 2011 was the anomaly that such a large residence had no internet connection or phone line.

“It’s possible that small improvements in safety and security aren’t going to be sufficient [to allow us to continue] everything that me and my colleagues did in the past to generate clandestine intelligence through personal interaction,” says Wise. “We might have to rebuild human intelligence from the ground up, in terms of tradecraft. What’s going to change is the alias business: you’re not going to be able to do anything except what you’re able to do within your real existence. Good luck with entering China without the Ministry of State Security knowing more about you than you know about yourself.”

Without wanting to tempt fate, there is agreement that the scale of the threat of Islamist terrorism has diminished due to intelligence agencies getting better at disrupting plots and potential terrorists losing interest. The focus of the future appears to be a return to competition between rival states.

“Perceptions of threat will be wildly different,” says Ciaran Martin, chief executive of the UK’s National Cyber Security Centre, which is responsible for protecting government communications. “Going into this decade, it was clear for the first time in a long time that terrorist threats coming from fragmented states are less strategically important than they have been for quite a while. Great power competition played out in the modern sphere of a highly networked society is where it’s at for intelligence services.” That great power competition involves – most significantly and most obviously – the US, China and Russia. While this is a statement that could have been made for much of the past 50 years, the nature of the rivalry has evolved. During the cold war, the US was not economically enmeshed with the ussr, the latter was attempting to export a global ideological revolution and China was principally focused on its domestic development. None of those statements is now true.

“There’s a fashionable phrase going around that Russia is very bad weather and China is climate change,” says Martin. “We tend to sometimes lazily talk about Russia and China as though it’s a double act but they’re very different. Russia has a desire to project power but is not seeking to dominate the western way of life, so it will do things like seek strategic advantage for itself through cyberattacks and so on. Whereas China is a different model of organising a society, which the Chinese Communist Party believes in – and it intends to continue with [it] until China is the most economically and politically powerful force on the planet.”

“The Chinese want to own us and outcompete us,” says Wise. “So they’re looking for data that will support that strategic goal. The Russians want to destroy us. If you crawled through the US power distribution network searching for malware that is triggerable by the owner to damage the infrastructure, I’ll bet you wouldn’t find any Chinese malware whatsoever. For the Chinese, dropping the East Coast power grid means that Wall Street is out of business, so the ability of the Chinese to do global business is going to be seriously affected. That’s not in their interest. But you’d find a tonne of Russian malware.”

“People talk a lot of nonsense about how anybody can do a cyberattack; that’s not true,” says Martin. “Anybody can do a basic cyberattack but for a really lethal cyberattack, you have to have capabilities, money, skilled people, an operating environment where you can do that sort of work over time. If you’re a stateless terrorist group hiding from US and allied forces, you don’t have any of those things. If you’re a functioning nation state like Russia or China, you can.”

It seems clear enough that the intelligence operative of the future will spend a great deal of their working days squinting at lines of code on a screen, especially as artificial intelligence and quantum computing develop.

“We’re going through a shift in which collection and analysis, which used to be two separate elements in the intelligence cycle, are now getting closer together,” says Yossi Kuperwasser. “The analyst has to be much more involved in the collection effort and the collection agent should be much more attuned to the necessities of the analyst.”

“You need people who can perform artistic work. So you need a variety of people”

Kuperwasser also believes that intelligence agencies need to be more expansive in who they recruit. There needs to be less emphasis on collecting information, of which there is no longer a shortage, and more on interpreting and analysing the infinite universe of data now available. Machines will be able to do some of that; they won’t be able to do all of it.

“The secret of intelligence is imagination,” says Kuperwasser. “There are a lot of professional skills you need for a successful intelligence agency but you’ve got to have some people around you who are artists. Intelligence is an art, and you need people who can perform artistic work. So you need a variety of people. This is where intelligence agencies fail because they don’t have imagination. Recently the uae and Bahrain decided to normalise relations with Israel. This is a huge change. And any intelligence officer would have told you for ages that this isn’t going to happen; that it would never happen. But it did happen. That is something for which you need an artistic, imaginative way of looking at things.”

This spectrum of abilities will be just as essential in the increasingly vital online realm: a buzz phrase of 21st century intelligence is “protecting the digital homeland”.

“As the technical sciences and humanities come together, so too will the skillsets needed to do the job,” says Professor Paul Taylor, director of the Centre for Research and Evidence on Security Threats. “We should expect to see more behavioural scientists who are skilled in coding and engineers who have a deeper appreciation of how the ways in which a user will use their technology. Of course, as with all sectors, there is a balance to strike between depth and breadth of expertise. One way of addressing both is to broaden the diversity of those doing the job, which is something that the UK agencies have been doing successfully for some time now.”

And all those machines will be built, directed and operated by human beings, with vulnerabilities that will still be required to be explored and exploited. “There will be more of a balance towards humans taking action via computers and digital means,” says Ciaran Martin. “But if you look at the history of cybersecurity, there’s an awful lot of human interaction in it – an awful lot of psychology, of understanding how human beings work. There are still things that have to be done by going to difficult or hostile places and seeing what you can find out.”

Who to spy for?

Here are some perks – and pitfalls – of the job to consider:

HQ

Germany’s bnd opened the world’s largest intelligence headquarters in Berlin in 2019. The exterior is decorated with fake palm trees, which German authorities confirmed were, in fact, merely fake palm trees, not listening devices.

Recruitment

The UK’s gchq has been known to run recruitment ads through Xbox Live, hoping to tempt couchbound fantasists into trying their video game swashbuckling for real – or attract potential boffins with a gift for decision-making. It has also published a series of official puzzle books.

Diversity

The UK’s Secret Intelligence Service – or mi6 – is keen to slough off the employee stereotype of private schoolboys. Their website urges the curious not to worry if “you think you aren’t ‘from the right mould’, don’t have the ‘correct’ experience or did not go to the right university (!).” The exclamation mark is theirs.

Motto

Most intelligence service mottos are bland, corporate-sounding mission statements. The Czech Republic’s Security Information Service (bis) stands out with the elegant “Audi, vide, tace” – “Hear, see, be silent”.

Logo

It can definitely be said of Russia’s gru that they embrace the Bond villain schtick with gusto. The emblem of its special forces wing is the silhouette of a bat hovering over a radar screen.

Dramatic representation

While intelligence agencies of all kinds are catnip to screenwriters, few have been flattered quite like France’s General Directorate of External Security have been by television series The Bureau.

Gadgets

In September 2020 the cia announced the launch of cia Labs, an in-house r&d hub where officers will be permitted to keep 15 per cent of income generated by anything they invent. Israel’s equivalent, Mossad, operates its own technology investment fund, Libertad – which is seeking funding applications on areas from synthetic biology to personality profiling and robotics start-ups. They’re either building an actual Terminator or winding up the world’s conspiracy theorists.

Notoriety

Russia’s gru have lately been responsible for more than their share of headline-catching foreign operations. The downside is that those involved might be obliged to appear on television unconvincingly claiming to be cruelly maligned cathedral enthusiasts.

Case assignments

In July 2020, fbi director Christopher Wray estimated that the agency was pursuing about 2,500 active cases pertaining to Chinese espionage and opening a new one every 10 hours. “If you are an American adult, it is more likely than not that China has stolen your data,” he says.

Retirement options

Former US spooks have options that are the envy of their counterparts elsewhere: a ravenous media with hours of talking-head airtime to fill, films and television shows seeking the expertise and gravitas of former spies, even an entire Spy Museum in Washington. And the best part: if you’re making it all up, who is going to know?