New food nation: Brazil / Brazil

Fare game

Who will be the new food nation? Peru and South Korea are out in front but what happened to Brazil? It’s the nation we love everything about except its food – but here’s how it can change that.

Food defines a nation. The precision of sushi, the excess of a double cheeseburger and the haughtiness of haute cuisine all betray the character of their creators. But what of Brazil? Few countries are perceived as positively abroad; stereotypes of warm welcomes in warmer climes muddled with bossa nova, samba and tropical modernism have traditionally travelled well. Yet Brazilian cuisine never seems to make it past customs. It’s hardly what you crave on a Saturday night.

Countries have always used food to ease dialogue and make friends. Today the notion has shifted from hobby to economic necessity as farsighted governments use it as a branch of foreign policy by investing in programmes that push their produce overseas. Food has become the ideal soft-power tool.

For inspiration, Brazil needn’t look far. In 2002, some bright bods in Bangkok launched the Global Thai scheme, aimed at increasing the number of Thai restaurants around the world. By 2013 the total had risen from 5,500 to over 20,000. Similarly, South Korea invested more than €60m in the Global Hansik project in 2009 with the hope of beefing up its international presence to a whopping 40,000 Korean restaurants worldwide by 2017. Likewise, Brazil’s Andean neighbour Peru launched the Cocina Peruana Para El Mundo (Peruvian Cuisine for the World) initiative to raise the quality of its fare; the ultimate goal is to have its food recognised by Unesco under the Intangible Cultural Heritage of Humanity category. And it is working. Peruvian dishes and pisco sours are popping up on menus around the world. What’s more, it means much more than just a PR push: a food culture that travels increases revenue from tourism.

Unfortunately this is not the case in Brazil. Part of the problem is that the cuisine, like the country itself, is hard to define: a mish-mash of intangibles that presents a problem for the branding brains intent on repackaging it for global consumption. Even the most daring foodies willing to brave the lacklustre Brazilian restaurants abroad would be hard pressed to know where to begin. Be it tacacá no tucupi prawn broth made in the north to acarajé (a deep-fried bean paste from Bahia), moqueca, a fish stew from Espirito Santo, pão de queijo cheese bread or the national dish of feijoada, Brazil’s best dishes will need some deft positioning to tempt diners in New York, London or Tokyo. But then who could have predicted that raw fish, seaweed and wasabi would one day be one of the world’s most popular lunch options?

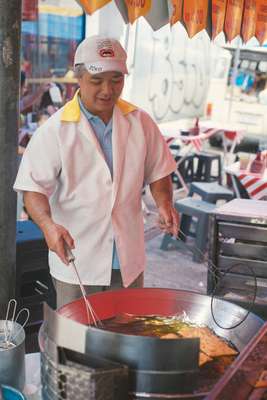

Current moves to raise the nation’s game are enthusiastic but insufficient. Festivals such as Folia Gastronômica in Paraty may be on the rise but food trucks full of pasteis and petiscos are small fry by international standards. Rogério Fasano, Brazil’s best hotelier, jokingly encapsulates the challenge for the country’s culinary culture in the decade ahead. “Don’t ask me about Brazilian cuisine,” he says. “I’m Italian, why would I eat anything else? I like my food Italian, my cars German, my wine French and my women Brazilian.”

But entrepreneurs who have invested in the nation’s native produce have been pleasantly surprised. Nico de Virieu, co-founder of London-based Dri Dri ice cream, was responsible for bringing artisanal gelato to Brazil and began experimenting with flavours in the firm’s São Paulo shop. “We had to change our recipes because Brazilian ingredients are so good and so diverse. We have queues around the corner every day,” he says.

For all its shortcomings in unshackling itself from hoary old perceptions, Brazil can benefit from the overwhelming good will it inspires abroad. All it needs to do is leverage that positive global image into realising the hitherto untapped potential of Brazilian produce on the world stage.

Recipe for success

So, Brazil has the raw ingredients and talent to produce. Given the task of turning Brazilian cuisine into 2015’s success story, here’s what we would do.

01. Back talent:

A new generation of chefs including Alex Atala and Samantha Aquim is leading the charge to raise the profile of Brazilian cuisine. How about including them in the push for Brand Brazil, too? You need a chef who travels; is there a Brazilian Jamie Oliver?

02. Cough up the funds:

Government intervention has been underwhelming. The not-for-profit Gastromotiva uses food to generate social inclusion but it needs allies. “Brazilian chefs need to work with the government to build public policies,” says founder David Hertz.

03. Brand Brazil:

Brazil needs better branding. Édouard Malbois, founder of advertising agency Enivrance, laments how they still “overplay the stereotypes of Brazil in the 1960s and 1970s”. Having wasted the potential of the World Cup, efforts must be redoubled for the 2016 Rio Olympics.

04. Honour thy neighbours:

The good news for Brazil is that positioning projects have proved fruitful for nations who have gambled on their goods. Mezcal evangelist Silvia Barnett Sanchez targeted early adopters in New York and made the little-known Mexican spirit a worldwide success. Cachaça can easily do the same?

05. Sustainable growth:

Alan Bojanic, the director of fao-un in Brazil and a principle at Desafio 2050 says, “Brazil is in a position to teach the world good agricultural practice. Family producers can help innovate and uphold food traditions.”

06. Adopt the missionary position:

Federal tourism agency Embratur and Apex, the trade agency, should invest in dispatching culinary embassies to key markets and placing Brazilian stalls at international trade fairs. But leave the carnival floats and feathers at home if you want to be taken seriously.

07. Go on tour:

Brazil’s tourism industry is pitiful compared to those of its neighbours; its annual five million visitors is dwarfed by Argentina. From Seoul to São Paulo, Peru has built an entire industry around ceviche and pisco sour.

08. Invite the world:

You have a country 13 times the size of France. Bring international journalists, critics, chefs, hotel owners and investors to experience every facet of Brazilian cuisine from the farmers, fisherman and cowboys to the bright young things in the kitchen.

09. Export the unknown:

Brazil is already the largest producer of beef, orange juice and sugar cane in the world but is home to ingredients such as pupunha palm and priprioca root, which have the potential to be better known abroad.

10. Go for gold:

With almost two years until the Olympics in Rio there is time to create a campaign that includes cuisine. The world will be in town so invest in training to win medals in the culinary stakes and convince an international audience of Brazilian food’s worthiness.