Politics on TV / Washington

Politically switched on: The legacy

Why does political TV lack bite? How can it engage us? Look back at the golden age of American TV debates for the answers.

Meet the Press, which calls itself “the world’s longest-running television programme”, has always prized continuity over novelty. It first aired in 1947 on NBC and has appeared for an hour every weekend since, interrupted only for major sporting contests. For the US political class, Meet the Press has offered its own sense of occasion: John McCain has been a guest so often (69 times) that those around him snicker that the senator doesn’t have time for God because he already has a church to attend on Sunday mornings.

This autumn, just weeks before the midterm elections, nbc promised a modest overhaul of the show, replacing its ineffectual presenter David Gregory with the network’s White House correspondent Chuck Todd. With his Daily Rundown on the cable network MSNBC, Todd already hosted US television’s best hour of topical programming, pairing sharp political interviews with news analysis from top journalists. It was the Meet the Press mix but five days a week, stripping the weekend show of any discernible impact. Todd had liberated Sunday mornings; the political class could take up organised religion again – or at least a leisurely brunch. McCain will inevitably show up in Todd’s pews but why should any audience members do so?

This NBC palace history is something of a parable for the global crisis in political television. It may be hard to remember in the era of screens overcrowded with talking heads but there was once a golden era for the format. In the middle of the 20th century it was novel to observe a politician captive in a journalistic setting. What could be more refreshingly democratic than to unmoor a government official from the native environment of the campaign podium or parliamentary chamber? And what more thrillingly dramatic than to then subject him or her to a direct challenge in full, live view of the citizenry?

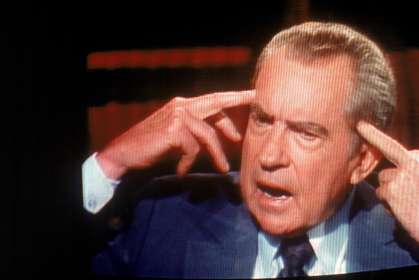

The on-camera encounters of the era are memorable both as television events and for their unique contributions to the historical record. Politicians who had spent decades managing their public images found themselves immediately undone on camera, forced by long-form conversations by well-prepared interviewers to concede weakness or inadvertent candour. It was over two sessions in 1979 for a one-hour CBS News profile that Ted Kennedy revealed himself unable to coherently answer Roger Mudd’s question, “Why do you want to be president?” It took 29 hours of tangling with Richard Nixon for David Frost to extract from the former president what prosecutors, subpoenas and the threat of impeachment had failed to: an apology for Watergate.

The electoral process quickly reimagined itself in the image of the talk show. In 1960, candidates John F Kennedy and Richard Nixon faced off in the first televised presidential debate; in effect it was an episode of Meet the Press produced from a Chicago soundstage for a much larger, prime-time audience. US voters had to wait until 1976 to see presidential candidates face off again (that year, vice-presidential running mates joined the practice, too) but by then overseas broadcasters had recognised the appeal of pitting candidates against one another for the benefit of viewer-voters.

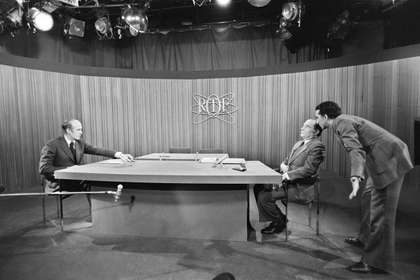

In 1974, French network RTF convinced presidential finalists François Mitterrand and Valéry Giscard d’Estaing to apply the 45 minutes of public airtime, to which each was entitled, to a joint appearance. Unlike in US debates, a pair of clocks hung over the Paris set to count down each candidate’s time. Debate director Roger Benamou’s next project may have been a French-language Othello but the ominous prop suggested a debt to Chekhov.

With time, other countries adopted presidential-style debates. German TV had party leaders face off for the first time in 1969 and the Dutch in 1977; Brazil, Kenya and New Zealand, among others, followed suit. In the US, televised debates have become an essential part of the campaign calendar for every office. During the 2012 presidential primaries, Republican candidates participated in 20 of them. Party leaders concluded that these ritualised on-air conflicts served the interests of network executives more than the candidates themselves. “I think a travelling circus of debates is insanity in this party,” said party chairman Reince Priebus.

By then there was so much political TV that candidate debates were distinctive only because they aired with the sanction of a party. Cable news is, in a sense, the debased Meet the Press format on 24-hour loop – punditry, interviews and argument in a perpetual wash-rinse-repeat cycle – with occasional digressions into true crime and missing planes. Across networks there are slight variations in tone and sensibility but rarely enough to make any one hour of politically minded talk more essential than the next.

This surfeit of political programming quickly upended the power dynamic between politicians and producers. Politicians who wanted airtime were no longer in thrall to a small cartel of shows that could set the terms of coverage. A one-hour interview on Meet the Press (or its competitors, ABC’s This Week or CBS’s Face the Nation) used to be seen as a crucial test for a prospective president but few agreed to such an encounter in 2012. Why risk an hour-long interrogation when one can opt for a 12-minute version on Fox News (for conservatives) or MSNBC (for liberals) where the questioner isn’t scheming to humiliate you?

What made great political television possible wasn’t great politicians so much as scarcity. Politicians weren’t perpetually available to the media and the journalists who confronted them had limited opportunities to reach an audience. Producers need to reimagine the format and create an hour of political programming for which it’s worth waiting until the weekend.