Technology I: biomechanics / Calgary

Running Ahead

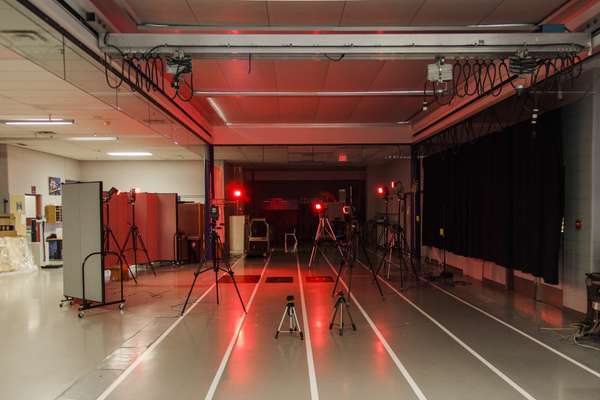

Working with sportswear giants to develop top-of-the-range running products, the University of Calgary’s Human Performance Laboratory brings innovation to a whole new level. We head to the lab to find out what you can expect to see on running tracks of the future.

Though the temperature outside is well below zero, the athletes at the University of Calgary’s Human Performance Laboratory are working up enough sweat for their sensors to peel off. Two research assistants, Bill Wannop and Ryan Madden, are adjusting the settings on a machine stamped “Parallel Robotics Systems Corporation”. A running shoe tied to an artificial foot and connected to a shiny metal cylinder where the leg should be is being dragged along a slowly moving patch of artificial grass. They are looking for the shoe’s traction sweet spot where grip isn’t outdone by injury, Madden explains. Just a few months earlier, the lab’s nearly 200 staff had been watching on with glee as Kenyan athlete Dennis Kimetto blitzed the marathon world record by 26 seconds in Berlin. Kimetto, the runner-up and the top-two female finishers were all wearing a model of ultra-light, ultra-comfortable Adidas shoes that for years have been a focus of work in this building.

It will be a few years more before the products the lab is working on today hit the track. Alongside the manufacturers’ constant explorations of new materials, the university’s researchers point excitedly to innovations with wireless sensors and portable kits to monitor and measure movement and muscle activity, both on sporting fields and in shops. Their work is a constant quest to understand this data so that they can better reflect the human body’s inherent notion of “comfort”. It is this, they say, along with new possibilities for individual tech customisation, that will provide the foundation for world records in decades to come.

Since its beginnings in 1981, when Olympic rower Roger Jackson lured biomechanics pioneer Benno Nigg to Calgary from Zürich in the lead-up to the 1988 Winter Olympics, the Human Performance Laboratory has grown into one of the world’s most important research centres for human movement. As part of the university’s Faculty of Kinesiology, its focus is multidisciplinary and unashamedly commercial, embracing what professor Darren Stefanyshyn calls the university’s entrepreneurial approach to research and intellectual property.

The lab and its commercial offshoots, such as Biomechanigg (now owned by Benno’s son Sandro), have established long-term relationships with brands including Adidas, Reebok and Mizuno. The recently semi-retired Benno, recovering from hip surgery in Switzerland (and off his crutches in three weeks like a true master of biomechanics), estimates that as many as 50 per cent of people working in the field worldwide have passed through the lab. “If you look at labs that deal with human movement, exercise and sport, I don’t think that you will find many others in the world that are as good as ours,” he says. “As a matter of fact, I don’t think you will find any.” Indeed, on a recent trip through Nike’s lab facilities in Oregon it was claimed that most of the people performing tests had probably graduated from Calgary.

To hold some of the shoes in the Calgary lab in your hand can be an unsettling experience: they feel so light that you may as well be holding nothing at all. The Adidas project that was a success at the Berlin marathon was the fruit of a 20-year collaboration between the company and the lab – Stefanyshyn in particular – built around a few meetings every year in which broad ideas were kicked about.

The proliferation of new materials and designs brings about understandable concerns that sports are being led by the equipment. For Stefanyshyn the mission of the lab is not necessarily to allow the body to perform as close to natural as possible but to optimise it for particular uses. Increased understanding of human-performance data and new analytics tools helps to reframe this optimisation, making it more effective than it has ever been before.

“Our foot is not naturally optimised for sprinting,” he says. “It’s not even optimised for marathon running. It is developed to be sufficient to do a lot of things very well. People want a fair playing field and that is a nice objective. But to have a different shoe, for example, to someone else: that’s no different to someone growing up in one environment rather than another. I’m sorry but nothing is ever totally fair.”

The lab’s reputation lures researchers from all over the world. Following a PhD in biodynamics at London’s Imperial College, Erica Buckeridge was eager to come to the snowy north for an opportunity to work with Benno, who she calls the “godfather of biomechanics”. She is now leading a project for Canadian workout empire Lululemon, researching the ever-elusive ideal of the functional sports bra. “That is one thing missing in the current sports market,” Buckeridge says. “You can’t combine comfort and function particularly well.”

Buckeridge’s research won’t lead to a new product on the market straight away; this is a long game and clients such as Lululemon are happy to invest in the process of understanding. “At the moment we are developing the analysis tools,” she says. “We need to be able to not just look at things in a traditional biomechanical way but push the envelope in terms of how we analyse our data.”

The future for the lab and its clients is digital. This has meant a shift in focus from footwear to a holistic understanding of data and its relationship to the human body, says Sandro. “If you looked at it 10 years ago, 75 per cent of the work being done would have been answering traditional footwear questions,” he says. “Today I would guess that this is at about 25 per cent. A lot of the dogma in footwear research is on the way out. Now you can monitor an athlete with respect to their health and readiness to play a game. You can put sensors on an individual and get them to perform a task, let’s say a soccer kick, and then compare their neuromuscular strategies with those of elite athletes.”

For Stefanyshyn, the most exciting developments in the near future are around the kinds of individualisation that these new sensors and approaches to data allow. “The big move forward over the next couple of years will be in the simplistic measurement techniques that can allow us to specifically fine-tune equipment to an individual,” he says. “You can do these things because we are getting all these wireless pieces of equipment that are very easy to use and can be individualised.”

For all of the Olympic medals and world records that the lab can lay claim to having had some part in, both Benno and Stefanyshyn point to the lab’s influence on performance and its shaping of thinking in the commercial world as its greatest achievements.

“We have populated companies such as Adidas, Nike and Li Ning in China with graduates and postgraduates,” says Stefanyshyn. “It isn’t just what we produce: it’s the people that we produce and the impact they have that continues on.”