Report / Basra

Rock the Basra

Iraq has plans to build a shipping route that’s a cheaper alternative to the Suez Canal, starting with a port just south of Basra. It’s the biggest project ever undertaken by Iraq but will the war-ravaged city’s residents benefit?

Captain Omran Radhi can barely contain his excitement as he opens a plastic-bound agenda to a map of the world and explains Iraq’s plans for regional domination of the shipping industry. “You see?” he says, pointing to the pastel-coloured countries of Asia – the source of most of the world’s cargo. “This is China, this is Shanghai, this is Taiwan, this is Singapore, this is Malacca Strait, this is Bengal, this is Ceylon,” he points out. Magical-sounding names from another era. Captain Radhi has visited them all at sea before taking over as director of Iraqi ports.

These days, backed by the lure of contracts worth billions of dollars, his time is spent rubbing shoulders with the Italian foreign minister and recently the US transport minister. “When I explained our plan he told me this will be a revolution!” he says.

It is one thing reaching Basra by ship from elsewhere in Asia, quite another to get further west. It is another 18 days through the Horn of Africa, the Suez Canal and Gibraltar to the North Sea and Europe. Enter Iraq’s grand plan. By expanding the Faw Port south of Basra and building a railway to carry goods from Basra to Turkey, shipments could leave China and be in Germany in five days. The expansion would provide a much cheaper alternative to the Suez Canal route. With an estimated capacity of almost 100 million tonnes a year and a one million sq m container yard, Faw would be the third biggest port in the world after Singapore and Shanghai.

All of which sounds fantastical except for Iraq’s huge oil revenue – forecast to rise to up to $200bn (€154.5bn) a year – and the fact that the project has already started. In November, foreign companies in the $6bn (€4.6bn) first phase of the project will start work on a breakwater at Faw – the first step in expanding the port on the peninsula once occupied by Iranian forces. The entire $50bn (€38.6bn) project would be the biggest in Iraqi history.

Further along the Persian Gulf, Iraq’s main port at Umm Qasr, though heavily damaged in 2003, has experienced rapid expansion. “Our country has undergone three wars. They destroyed everything,” says Captain Omran in his office in the same port authority building built by the British in 1937. “All the equipment, all the jetties were destroyed. We very quickly developed the port and went to work again.”

To Iraqis, the port of Umm Qasr, the country’s gateway to the Shatt al Arab and the Gulf, is a symbol of national sovereignty. In the 2003 invasion of Iraq, British forces landed in Umm Qasr, as the Iranians had tried and failed during the bitter Iran-Iraq war two decades before. The Iraqi military kept fighting for the port for days after Baghdad fell. “We have all the potential to be an economic capital,” says Haithem Kathem, deputy director of Umm Qasr’s north port, the country’s busiest. “But we have a central government administration that doesn’t give authority to the provinces… If we had the authority here to make decisions you would see a different port.”

In Basra, the entire area is littered with the debris from three wars. By the docks, an Iraqi ship hit by a US missile in 1991 after Iraq’s invasion of Kuwait lies on its side, rusting into the sand. Ships sunk during the Iran-Iraq war still clog entry to al-Maqal port in Basra, now being renovated by an American firm as part of Iraq’s attempt to become a regional hub.

Kathem worked here in 2007 when Iranian-backed militias controlled cargo going in and out. Security has improved dramatically since Prime Minister Nouri al-Maliki gambled on sending in the Iraqi army to retake Basra and Umm Qasr from the militia in 2008 but, as Kathem points out, “In Iraq you can never say security is 100 per cent.” With 70 per cent of Iraq’s oil exported through Basra province and the biggest oil fields in the south, the potential wealth is enormous. But dictatorship, war and trade sanctions have left a government ill-equipped to administer those riches. There’s an increase in unskilled jobs but not much of the money is trickling down.

Back at the port in Basra, Mohammad Jassim loads huge sacks of Chinese cement from the Yangtze Grace onto a truck. Kurdish truckdrivers prepare to drive it away. Jassim has been working at the port since he was 10 years old. His father disappeared during the Iran-Iraq war, presumed dead. At 25, he has a seven-year-old daughter and a five-year-old son. After paying for transportation he makes about $20 a day. “I think things will improve but it will take a lot of time,” Jassim says. Even for deputy port director Kathem, after more than 15 years as a chief engineer, he can’t afford to own his own home.

“If he were corrupt he would have a huge house,” says one Iraqi. Like most, he believes that almost all of those with money in Iraq have made it through corruption. Five hundred and fifty kilometres from Baghdad, there is a resentment here that the oil wealth on their doorstep hasn’t improved their lives. Basra is one of the hottest cities on the planet: summertime temperatures hover around 50c. Two years ago, demonstrators were shot by Iraqi security forces in a protest against constant electricity cuts. This October, former Basra governor Misbah al-Waili was assassinated as he was driving his car in what was widely believed to be a political killing.

The killing seems to have had little effect on foreign oil workers who fly in without ever going into Basra city. On the edge of the Zubair oil field 45 minutes from downtown Basra, Dubai-based and European-run Petronor has created a self-contained mini-city for the oil field service industry. Named Iraq Energy City it includes offices, accommodation, a world-class medical clinic and plans for a kindergarten for working Iraqi women. “Although we are expats we are a locally grounded company and we consider ourselves an Iraqi company,” says Hans Hoiskar, the Norwegian managing director and founder of the company who has done business in Iraq since the 1990s. “We didn’t fly anyone in to do the job unless we had to… We’re trying to do as much of the purchasing as we can from Basra or Baghdad but mainly Basra because that provides jobs. The more jobs and more Iraqis we have, the safer we are.”

While technology means the oil fields provide enormous revenue but little employment, another Basra megaproject has begun putting people to work and changing the city’s skyline. On the edge of the city, 4,000 Iraqi, Indian and Bangladeshi workers are building Basra Sports City, a 65,000-seat stadium that will be one of the biggest in the Middle East.

Designed by the American architectural firm 360 Architecture, the stadium’s fibreglass and weathered metal panels look like the trunk of one of Basra’s famous palm trees. The complex will also include a smaller 10,000-seat stadium, an artificial lake, hotels and apartments. Unusually for such a large project in Iraq, the contracting partner is an Iraqi firm – the Abdullah al-Jiburi General Contracting Company – headed by a Ramadi businessman. “We build a lot of roads and industrial buildings but this stadium is unique,” says project manager Abdul Hussein Ali Hamza al-Khafaji, whose company is also building Basra’s overpasses.

He says Basra, with its educated workforce, oil and ports, could be rich if its wealth was managed properly. “Maybe 20 or 30 years ago everybody dreamed of coming to live in Basra,” he says, “but because of the destructive policies of Saddam and the past nine years, Basra went down and the other cities went up.”

For a city 1,400 years old the past three decades are just a blip in history. But no other Iraqi city has borne as much of the brunt of recent turmoil. In the Iran-Iraq war, the Basra region was the front line. It was the route for Iraq’s invasion of Kuwait and its catastrophic retreat out. The failed uprising here after Iraq was driven out of Kuwait was followed by a brutal crackdown and the city was neglected by Saddam’s regime for the next decade. British forces were widely blamed for cutting deals with militias here to avoid more fighting before they retreated to their bases and then pulled out entirely.

In the 1970s, Juliana Dawood was a university student wearing short skirts and going to the late show at the cinema without worrying about safety. Now there are no cinemas, almost no night life, and in a city famous for its poets, intellectuals and artists there’s not a single art gallery. When the militias ruled the city five years ago, music and secular poetry were effectively banned. Women and girls were threatened with death if they didn’t dress conservatively. Many stopped working.

Dawood, a professor of English at Basra university, says she’s not optimistic about the future. “This is a war-torn city – it has to heal from many wounds, different types of wounds,” she says. “In everyday life we’re struggling so hard for rights – human rights and personal rights. We’re not progressing on that.”

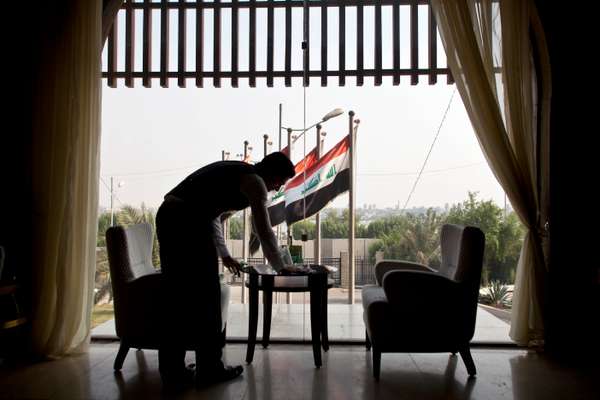

There are some signs that things are changing. On a recent evening in a restored house in Basra’s old quarter, Dawood sits with a US diplomat and a dozen Iraqi high school students enrolled in a two-year programme to teach them English and American culture. As the British government retrenches in Basra with the closing of its consulate, the US state department is taking advantage of the city’s relative security.

At this gathering security for the Americans is low-key. When the lights go out, as they frequently do, no one flinches and the students turn their mobile phones into torches. They happily chat with an American engineer brought in for the informal class – asking him what kind of music he listens to and whether he likes soccer. “No, sorry,” he says. “I like American football.”

Brent Maier, in charge of public diplomacy at the consulate, corrects their pronunciation from British to American English, including dropping many of the vowels in order to sound like a native speaker. “I love our British brothers,” he tells them. “I just think American English is better than British English.”

These are optimistic kids. They are middle and working class students looking forward rather than back, focused on what freeing the country gave them rather than what it took away. They don’t remember the days when the canals in Basra’s historic quarter outside the door were full of fish rather than choked with rubbish and rats. “In Saddam’s time they didn’t even have cell phones,” says Shams Salem. “Now we are getting to know new cultures every day. We are finding out new things, we are learning more languages. Our society is opening up.”

The new stadium is “awesome” they say. One of them says what Basra needs is McDonald’s and Burger King – also declared “awesome” by those who have visited them in Dubai and Jordan. What do they think Basra will be like in five years? It will be like Times Square, they say, and if not Times Square, they’re convinced it will, eventually, be “awesome”.

Port time

Iraq’s huge port project includes plans to build a railway line first envisioned in 1911 when the country was part of the Ottoman Empire. The Baghdad-to-Berlin railway was completed in 1940 but never linked to Basra, where ships could carry spices and other goods from India to Europe in competition with the British-backed Suez canal. The new 150kmph rail system planned by the Iraqi government would link Basra to Baghdad and then Zahkho in northern Iraq and across the border to Diyarbaker in Turkey. To account for the unpredictability of relations with its neighbours, an alternative route would bypass Turkey for Syria’s port of Baniyas. “Politics is like that. Today it may be bad but tomorrow it will be sweet as honey,” says ports director Omran Radhi Thani.

Scoring goals

Basra Sports City, one of Iraq’s biggest projects since the war, is due to be completed early next year. The 65,000-seat stadium includes a 10,000-seat secondary stadium, marble-covered VIP areas, four training fields, housing for athletes and hotels. A later phase will include an artificial lake in the shape of Iraq. The stadium is in the shape of a date palm trunk and the gate is modelled after the bow of a ship. “We didn’t want to create a feature that looks like every other stadium,” says Greg Green, the lead project architect for 360 Architecture. This year’s Gulf Cup football tournament was moved to Bahrain from Basra due to security and infrastructure problems but the city expects to host the 2014 event.