Travel / Morocco

The Drive, Morocco

Morocco can be vivid and unpredictable – we crisscross this dreamy landscape to uncover some of its mysteries.

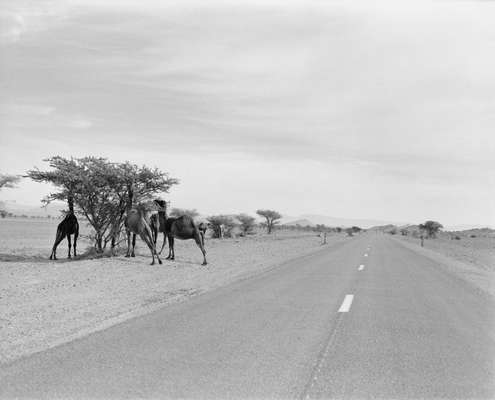

It’s easy to make plans and promises but the Moroccan road will surely break them. Distances are mirages. Towns hiss past and days slip by as the world changes from rock to oasis to moonscape; from red to green to brown to yellow and back again. In the desert the radio dies away and lines from songs circle in your head as you wonder at the horizon. The police, grey-uniformed, smart and stern, will detain you and you’ll need to stop for camels and sheep and goats and gas and water and hitchhikers and to ask the way. The morning muezzin will wake you at 5am with a loudspeaker. Tea in the Sahara – sacramental, ceremonial, social – will require at least half an hour, if you do it right. But it’s the country itself that stops you in your tracks. At every turn Morocco, like a salesman in a souk, conspires, takes you to one side, whispers that this outlook is finer than the last, that this hill or that valley’s impossible geological glory is the definitive article. That this is the picture to take, that is the line to write. It’s easy to make plans and promises but the Moroccan road will surely break them. Lucky old you.

In Essaouira after a warm, thick night drinking Stork and smoking kif at Le Trou, crêpes and café nus-nus and the stiff Atlantic breeze of late March make it a fresh morning on the roof terrace of the Villa de l’O. The view is the finest from a hotel in town: resident-general Lyautey’s clock tower, built after the Treaty of Fez, gave Morocco to the French protectorate in 1912, the old kasbah and the cold, rolling ocean unbroken until the Americas. The evening before, at sunset, there were lovers lounging on the ramparts of the Skala de la Ville, once a defence from sea-borne enemies and now just a bulwark against the sea itself. Beside it the port’s blue boats creak on the tide, fishing vessels come and go from dawn till dusk, refuge to litters of hungry cats. The place is a hive of boat-building, net-mending and shouting – a fish auction is defined by the song of the auctioneer and the ceaseless sweeping of ice and water across flagstones, back to the brine. Big diggers gouge a new port next to the old but for the time being it is an industry unchanged for centuries.

But the road. The road fires due south from Essaouira to the surf town of Imsouane, shadowing the Atlantic on the way to the casinos and winter-sun all-inclusives of Agadir. Immediately it’s all yellow hills dabbed with the dirty green of olive and argan trees, as sun-blasted and indestructible as the goats that climb them, foraging the sour fruit. The goatherds are Berbers in – what else? – de rigeur jumpers and coats in the 30C heat. They’ll lose the outer layer when it gets to 50C in the summer. “Salaam lekum; sabah el kheir.” It’s good morning also from the roadside men selling honey and oil in old jam jars from the argan trees. They’re under patched parasols as bees buzz jealously around their lost labours.

We’re chasing the sun. Imsouane is obscured in unseasonable mist, the sea like a work by Sugimoto, and lo and behold, our eagerness is rewarded with the slow white-gloved ballet of the Moroccan police speed trap. Don’t smile. Don’t joke. It’s 400 dirhams and a byzantine charge sheet you just know was borrowed from the deathless intricacies of French bureaucracy. But this cloud has a silver lining: if we get caught again within 24 hours, we just show the form and we’re scot-free. “Bingo,” as they say in the cheaper end of Agadir. And a note on that city’s status as former sardine capital of the world and now a sort of promenader’s dreamland: there aren’t as many fish in the sea but it’s a super-sun microclimate that the road dips into in dazzlement, and out of in shade. Behind us now are the surf school, camper vans and the little port of Imsouane. Maybe next time, when we strap a board to the Land Cruiser and the ocean looks less like slate.

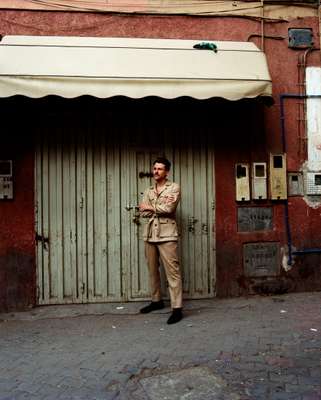

The road inland to Taroudant is a rare, flat thing. We follow the Oued Sous past palms, fields, farms and donkeys led by women in hijabs and djellabas, and cart horses whipped by grinning boys in Barcelona shirts; Messi has a handful of hay, Suarez wields a pitchfork. Taroudant is all “old town”, still happily hemmed in by mud city walls, dwarfed by the soaring High Atlas to the north and shading the green plain to the south. The kasbah is a moribund maze but the souq is electrically mercantile with heat and dust, meat and fruit and veg, carpets, cafés and spice. Of course we bought rugs. Our guide and lead negotiator is Anatole Maggiar, a debonair and very funny French art dealer with a family riad around the corner. It was purchased after a dinner party in town in the 1980s. After a postprandial candlelit tour at midnight a price was agreed and the key was posted to Paris. It took 20 years to bring the former pasha’s palace back to its vast aristocratic glory. “It was full of bats and rats and cats and cobwebs,” says Anatole. “But they renovated it slowly and used all local craftsmen – and it’s comfortable, no?”

It is a vision of time-stilled perfection in arcaded courtyards, minstrel galleries, pools, palms and songbirds bending the branches of lemon trees. Of course no one knows where it is; its small door is the most unassuming of entrances. God knows where our bedrooms are either; another midnight tour of the place is wholly accidental. The next day – after the first azaan is called at 05.21 by a muezzin in Willard White’s bass baritone – the Michelin 742 map, as is customary, is unfolded on the dusty hood of the Land Cruiser before we rumble south through the Anti Atlas to the oasis of Tafraoute. The villages are mud, not modernist, but the hills look Hollywood. We swing through Biougra and Afrada to the plain between Imhiln and Madaw, from which the Kasbah Tizourgane sprouts impossibly on its own hill rock foundation at Tiguissas. It’s like a fortified Mont Saint-Michel, like Bruegel’s “Tower of Babel”.

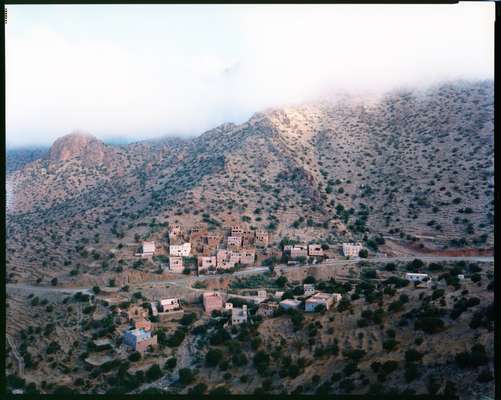

We roll and roll and the heat is hot and the ground is dry but the air is full of sound. Grasshoppers and songbirds and goats and, by now, the crackle of everything underfoot, crisp under the sun. A hundred men dotted sparsely along the road seek shade under anything: the angle of a road sign, a branch, a jutting rock. South and more south and red and more red gets the rock toward Algeria and real desert and a road out of Mad Max in a valley from Star Wars somewhere near Azemmour unfolds again. At the crest of a hill we find two couples, Austrian and Dutch, sipping coffee in camping chairs outside their huge Action Mobil camper trucks (they’re too big to be vans; their cabins are forged onto mighty lorry cabs). “The road looks even better from up here,” says Jan Van Haandel from inside the monster. “It’s like flying.” They’ve been flying for seven months and have three more left that’ll just roll on by. The offer of a drink is turned down: the road and plans and promises, remember? Back at ground level the terrain looks as if cowboys and Indians should be battling across it. Plains and hills with a single plucky, windswept tree clinging to the scree, then an oasis in a valley whose water lies deep underground. There’s another village clinging to the rock like a Greek monastery or a Thai temple, impossibly perched in a death-defying adjacency to the valley floor. Buildings, like the mosque here at Sidi Abdeljabbar, are literally built on faith.

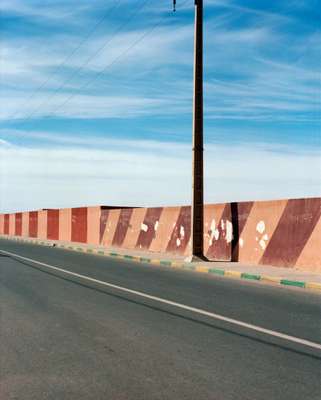

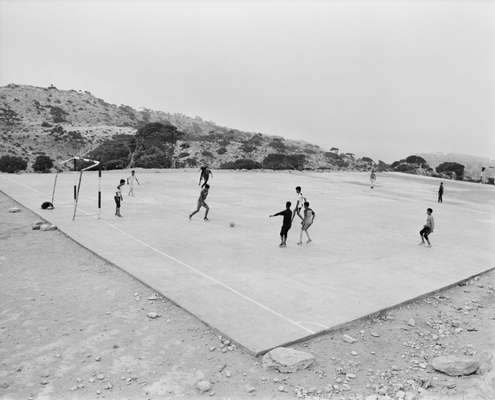

What does the road do to you? It bewitches and bewilders. Here, approaching the Ameln Valley, the road and its length and loneliness make solo travel sad and strange and dangerous. The kings of Morocco did not want the rural rush to the cities that has denuded small places of their populations – and have been the downfall of so many leaders – so Mohammed VI has built good roads between the towns and villages of the countryside. You can get to Fez and Rabat and Casablanca but there are few highways; they’re all equal under one king with a lane going one way and a lane going the other. Mobility and social mobility are simply entwined like few other ideas in politics. The road is both dream and danger.

Our own road now pours us downhill into the relative verdure of Tafraoute, the jewel of the lush Ameln Valley, beautiful as the dusk hits the red and granite of its rocks. And what rocks: like the discarded counters in a giant’s board game, tossed aside in a gargantuan tantrum. Rocks like sleeping elephants, rocks like a wind-sculpted Sphinx, rocks like big men in Francis Bacon oils, rocks doing it with other rocks, rocks like stalagmites and termite hills and whole cities thrown up a hill. As night falls there are rocks that watch you sleep.

We drive deeper south and east, a day where the sand creeps into everything and gritted teeth are no longer a turn of phrase. From Icht to Akka to Tata to Tissint, we drive almost to the elbow of desert that becomes Algeria, where the Saharan plain sits between that bittersweet neighbour and Jebel Bani; here we find a huge natural wall that was once a cliff – the plain was once an enormous sea. It is eerie, like a wave halted mid-swell. It is under this rock and under canvas that we’ll sleep fitfully, dreaming of scorpions on the pillow and an ancient ocean rushing down the stick-dry river bed.

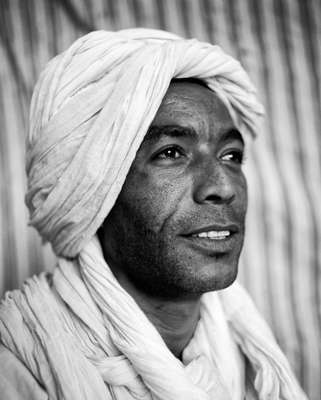

We’re far from a town but the early azaan still comes wafting across the plain, today as sweet as Smokey Robinson. It must be a miracle. The kid tagine and the fire are gone and sunrise is a work of art out here in the desert. The showers at the camp are candlelit; the beeswax and the sun vie a little to illuminate your ablutions but there can only be one winner. Soon the sun is fat and brilliant and the hills shudder with its heat. Our host, Mohammed, urges us to fill the tank and check the tyres in Foum Zguid. Vast sands can swirl from nowhere, he says, and a twister playfully swirls a few miles away on the plain, on cue. Maybe a mirage of a petrol station will shimmer strangely at us as we blink at our faltering fuel gauge?

The road to Agdz will take us to the Draa Valley and the palms, fields and little villages that prosper by its river. It is beautiful and lush and the boys support Manchester United sometimes too – and Real Madrid. As elsewhere we stop for tea and talk French to locals and roadside men. The police politely detain us once more, this time for a light-hearted exchange and a mere 200 dirhams that disappear, surely for reasons of mere convenience, into the pocket of the smart grey trousers. But we’re late and the dim lights are flickering. The stops and the photographing of camels, the issuing of sweets to children, the lying against the dusty car to make notes and taking pictures, all means that our date with a strange, sodden Marrakech soon approaches. It’s easy to make plans and promises but the Moroccan road will surely break them. Buy your map and plot your trip and double it. We make a wide U-turn and stop; it’s the end of the line.