Harris Tweed / Scotland

Ripping yarn

Harris Tweed is woven in a beautiful setting by workers in their own homes. But all is not as idyllic as it sounds. With the closing of its largest mill, it’s crunch time for the business. The question is, can things be turned around?

In the back of a noisy factory, on one of the most far flung corners of the British Isles, a young man opens a door to find a wall of freshly dyed pink wool. This is not just any old pink. It is Paris Pink and Fuchsia, he explains.

In a matter of seconds, the wool is forked into an underground tube and sucked away to be scraped, pulled, rolled, twisted and spun on an epic journey through decades-old machinery that will turn it into one of the world’s finest yarns. Some 40 highly skilled people will lovingly tweak and tease the wool with expertise they’ve learnt from their fathers and grandfathers. Once the yarn is made scores of weavers will pedal away for days on ancient looms in their homes to turn it into Harris Tweed.

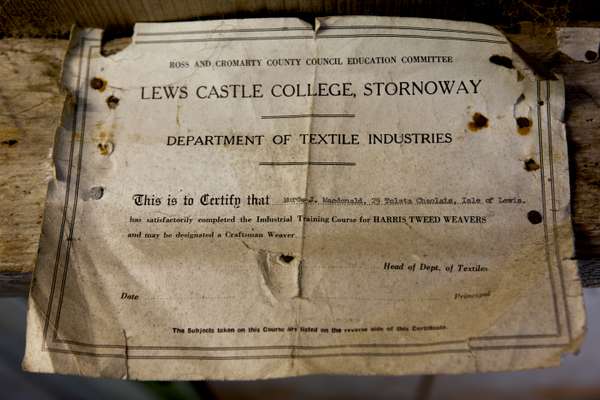

This is perhaps the most famous fabric in the world. Only the inhabitants of the Outer Hebrides, at the north-west tip of Scotland, know how to make it. And by law, only they are allowed to.

But because of infighting between the islanders and also globalisation, Harris Tweed very nearly bit the dust. It took weeks to get the cloth, it cost a lot and hardly anyone but the hunting and shooting crowd was really interested. Having made 6.9 million metres of the cloth in 1966, the island produced an all time low of only 547,762 metres last year. But right now, if you ask the experts in the tailoring and fashion industry, they’ll tell you Harris Tweed is “hot” again. “It is a unique, beautiful, iconic product that is in demand,” says Patrick Grant, owner of Norton & Sons, a Savile Row tailor.

The cloth – which the island has been making since the mid-19th century – is unique in many ways. The wool is dyed before it is made into yarn, not afterwards, which means the potential for new colours is infinite. “We’re like Dulux,” says Kelly Kennedy, who is learning to design colours and patterns from her father who has done it for decades. “Name your colour and we’ll make it,” she says, stood amid piles of samples and vintage patterns in the design room of Harris Tweed Hebrides’ mill at Shawbost. “Between this blue and that blue there is always another blue.”

Unlike other cloths, Harris Tweed can only be turned from yarn into cloth by weavers working at home. It is then returned to the factory where each piece is authenticated and stamped by the Harris Tweed Authority. If they want to, customers can find out who made their cloth and imagine him watching killer whales in the Atlantic from his window as he worked. “Provenance is more and more important to people these days,” says Lorna Macaulay of the Harris Tweed Authority in Stornoway. “There are people who would die and go to heaven for a product with such a strong identity.” So, it seems, the islanders should be in for a boom. The problem is, it may be too late.

In March this year, the largest of the factories (known here as mills) – which had been producing around 95 per cent of all Harris Tweed – closed down. Yorkshireman Brian Haggas is accused by many (but not all) of delivering the fatal blow. He bought the largest mill in the main town of Stornoway in 2006 and decided that the only way to make it profitable was to stop selling cloth and instead make one men’s jacket available in four colours.

The result? He’s got around 70,000 jackets sitting unsold in a warehouse and, he admits, their value has dropped from around £300 to just £70 each. “To put it nicely, we rather over did it,” says Haggas. But he is convinced these are just teething problems and ultimately he will drag the industry into the 21st century. Haggas has invested millions in new equipment for his mill and says it’ll be running again next spring. He says he’s planning to introduce a new jacket “for the young”, made with fabric he has “brilliantly and innovatively” named: Harris Tweed Light.

His approach has however caused widespread consternation. “One shortsighted strategy has effectively cut the legs off the industry,” says Grant, the Savile Row tailor.

In the meantime, two smaller mills have been revived to process orders for cloth. “We’re doing a roaring trade,” says Rae Mackenzie, sales director at the Shawbost mill. Working from a Portakabin next to the shabby old concrete sheds that house the mill, he presents a list of customers: Vivienne Westwood, Ralph Lauren and Paul Smith. Down the road at Carloway, at the smaller mill run by Harris Tweed Textiles, it’s a similar picture.

Some of the most experienced weavers sell their own designs direct to the customer. At his home on the island of Harris, Donald John Mackay, who began weaving alongside his father in 1971, carefully rolls his cloth onto a table and marks up the metres. He is sending off an order to Vietnam where the cloth will be made into soft Clarks shoes.

But the remaining tweed producers are struggling to make up for the fact that the largest factory on the island is now standing idle. Some complain that orders come all at once and late for each year’s winter collections meaning workers are busy for several frenetic months, cannot produce enough cloth and are out of work for the rest of the year. But major international clothing chains have no sympathy. Several have abandoned plans to place bulk orders because they cannot be sure they will arrive on time.

The smaller buyers, such as Cameron Buchanon, an Edinburgh-based merchant who sells on to tailors and designers worldwide, are still patiently buying the cloth despite having been let down before. “There is a very positive future for Harris Tweed,” says Buchanon. “But the industry needs a great shake up in order to seize the opportunity.”

The islanders are doing their best with scant resources (banks are not keen to offer them loans in the current climate) to keep their precious piece of national heritage alive. Either the mills and their weavers will find a way to hammer out enough cloth to meet demand or they will simply not be able to deliver. Most are aware that 2010 is probably make or break time for Harris Tweed.

Monocle’s recipe for success

1: The Scottish government needs to wake up and realise that if it doesn’t invest in Harris Tweed to help it get back on its feet, it could lose one of its greatest national assets.

2: Open a really good Harris Tweed shop in London, Milan or New York. Why not all three?

3. Hire a few Scandinavian marketing professionals. If they can convince designers and models to wear fur despite a worldwide campaign against it, they will have no trouble raising the profile of a gorgeous piece of cloth that keeps an island community alive.

4. Entice customers to visit Lewis. Once they have they’ll be hooked for life. And they’d be more likely to forgive the occasional delayed delivery.

Forever Harris

Since 1910 Harris Tweed has had a certified trademark, meaning it can only be made on the islands of Lewis, Harris, Uist and Barra, which make up Scotland’s Outer Hebrides. The definition was tightened in 1934, adding that the yarn must be made of pure wool and woven by islanders in their homes.