Business: Health & wellbeing / Lille

Shot in the arm

France is banking on the future of medicine. All it needs is a healthy dose of investment.

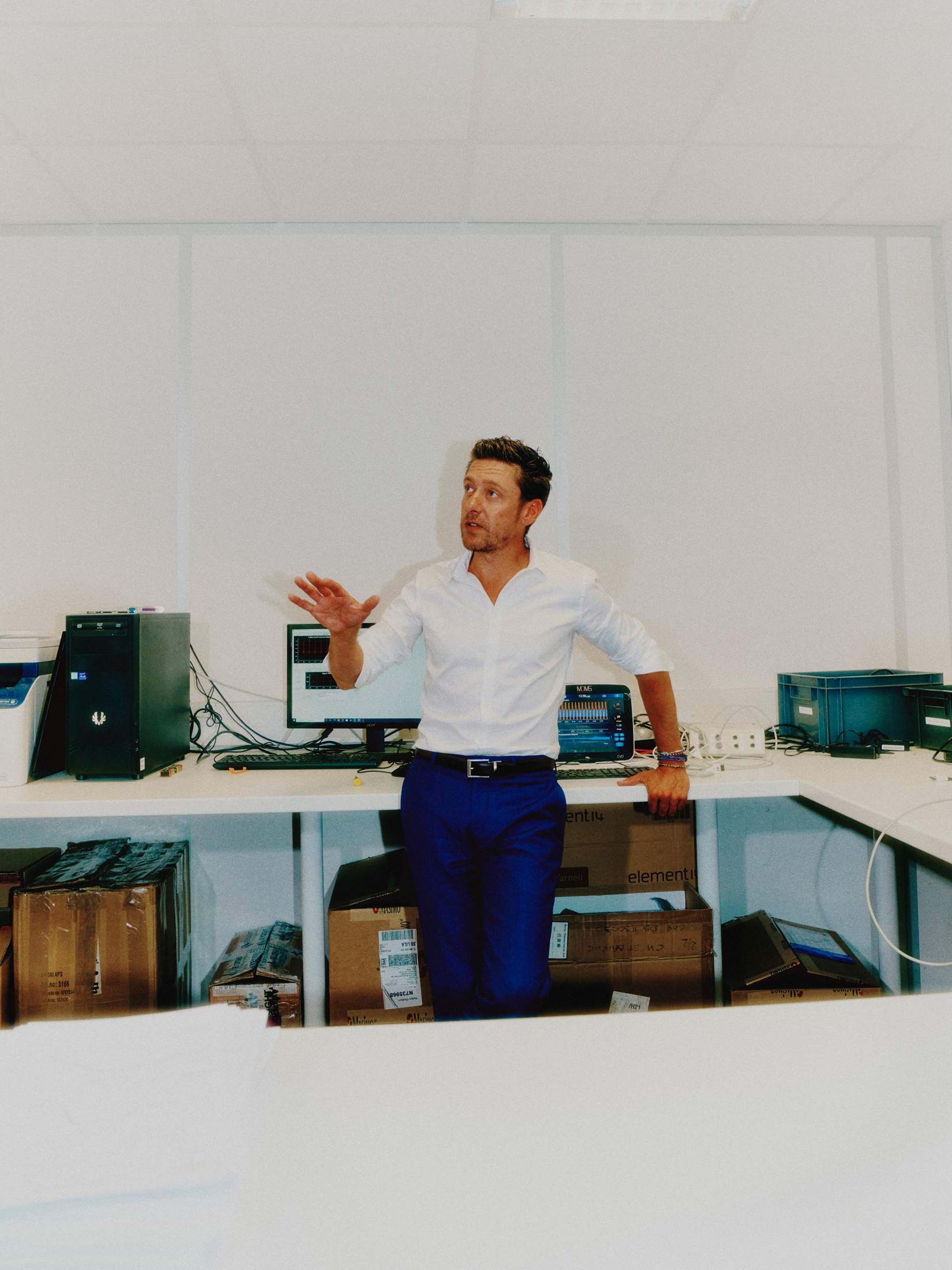

Sun-kissed and with his shirt sleeves rolled up, Fabien Pagniez is expanding upon the future of healthcare. “We will not need anaesthetists or surgeons,” he says from his company’s office and factory in Loos, on the outskirts of the northern French city of Lille. He’s referring to the potential that artificial intelligence has to revolutionise the healthcare industry. “All of this will be part of history.” Pagniez, ceo of MDoloris Medical Systems, has reason to feel hopeful about this brave new world: he’s at the forefront of it.

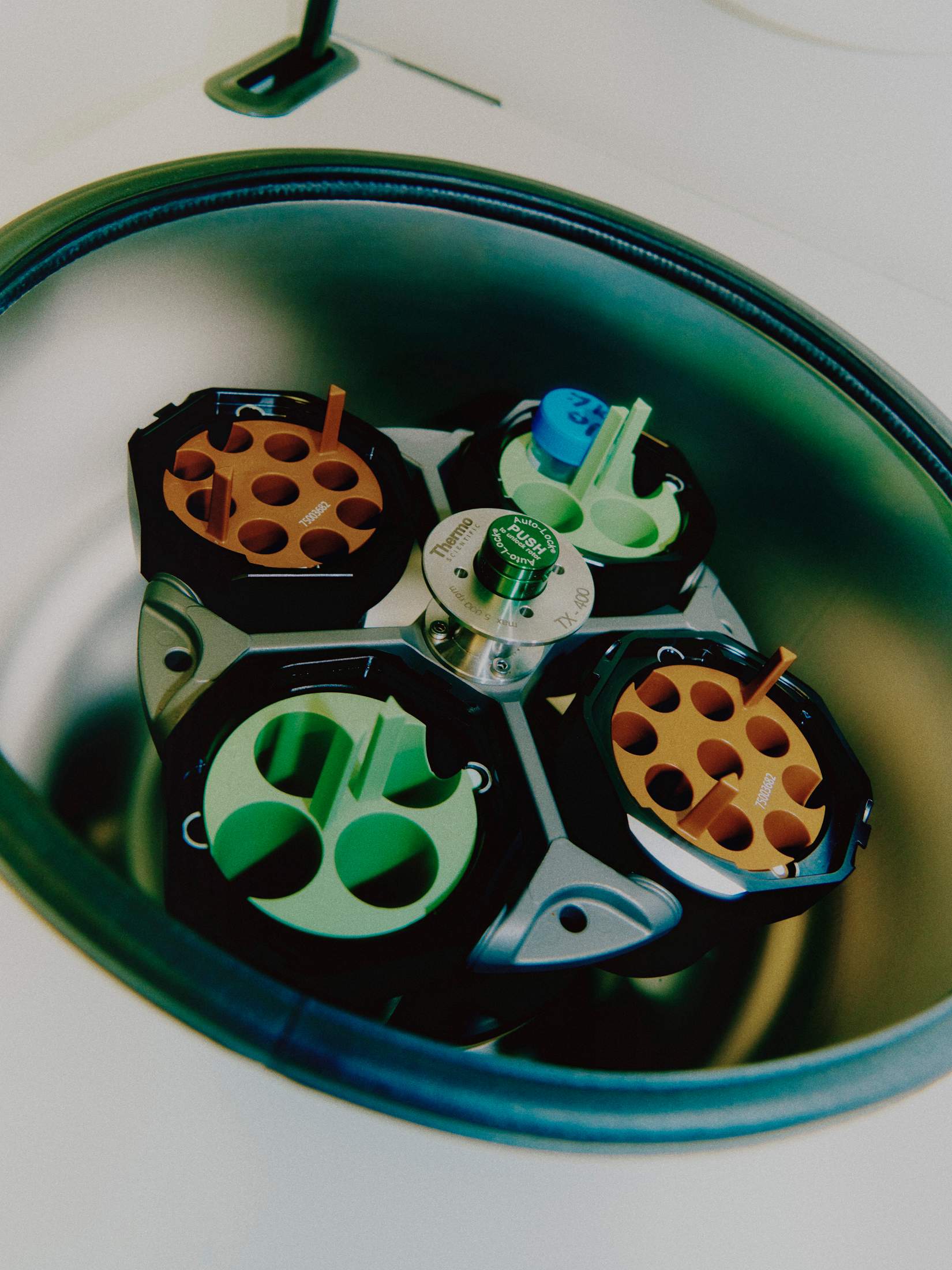

Cold storage at Lattice Medical

Etienne Vervaecke, Eurasanté’s general manager

Lab at biotech X’prochem

Fabien Pagniez at the MDoloris Medical Systems office and factory

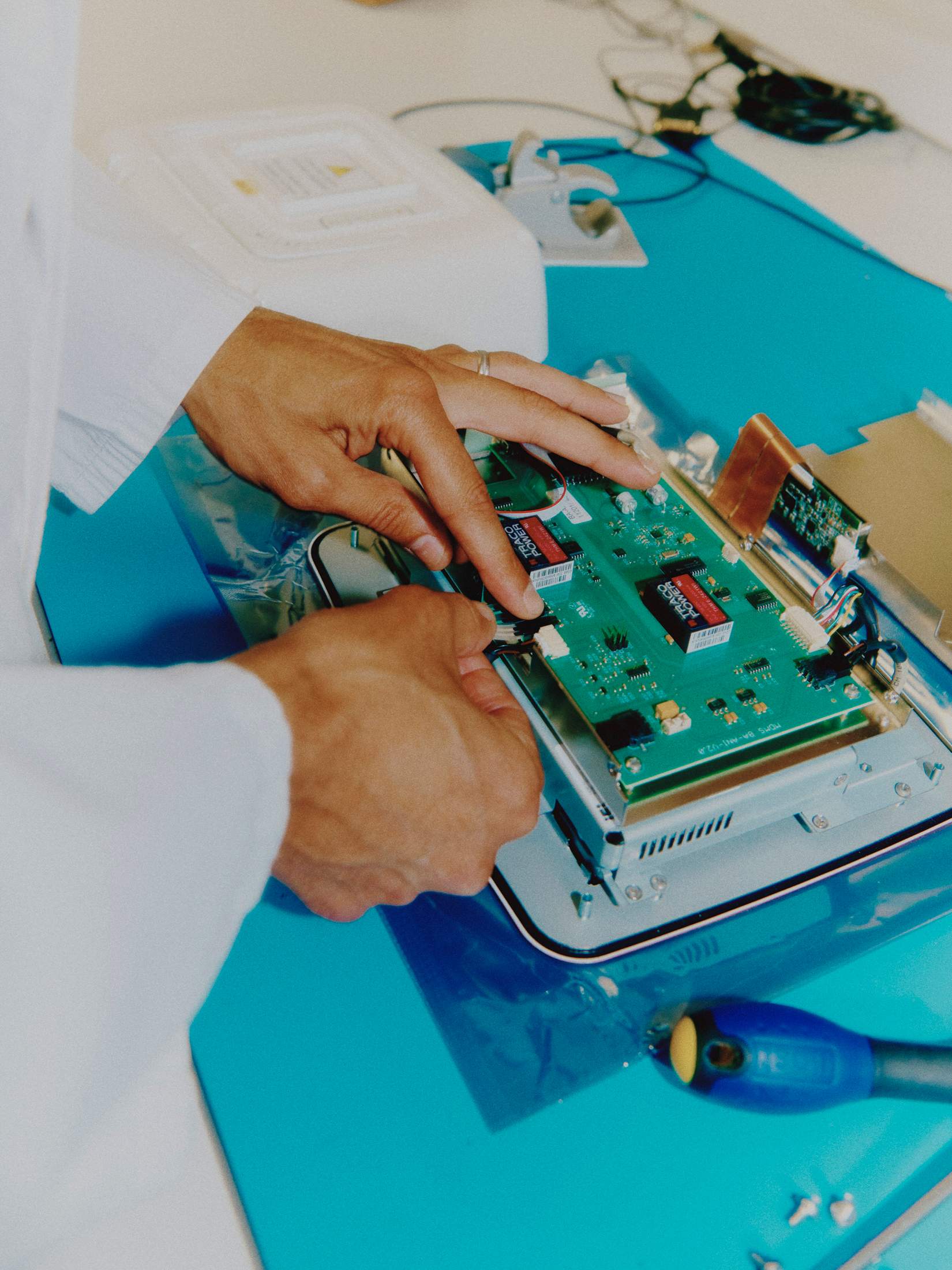

MDoloris, which was founded in 2010 and now operates in 76 countries, has developed a device that can measure the autonomous nervous system – or what Pagniez, in a gallant attempt to put things in layman’s terms, refers to as “the brain behind the brain”. The nervous system is responsible for the body’s physical reactions, including pain response, and MDoloris’s device, which looks like a standard operating-theatre monitor and clocks in at €10,000 a unit, gives readings that allow anaesthetists to measure in real time how much pain relief a patient needs during an operation. We watch as a small team beavers away screwing in circuit boards and mounting the devices, ready for boxing. MDoloris is also working on a prototype robot for administering drugs, meaning that Pagniez’s predictions may be nearer to reality than to science fiction.

The company is not alone in looking for healthcare’s next giant leap. The coronavirus pandemic, aside from turning everyone into amateur epidemiologists, has made nations pay more attention to their own industries. Vaccine nationalism has forced leaders to prioritise their healthcare sector’s capacity for innovation to a level similar to that of food security. France was notably slow in getting a coronavirus vaccine out of the gates, with Nantes-based Valneva only approved in Europe in late June. Emmanuel Macron has earmarked health as a key industry in his country’s future economic growth, allocating funds for improving competitiveness as part of a post-pandemic relaunch plan. A separate, bolder plan will invest €7.5bn in the sector in a move that promises to make France the number-one country in Europe for healthcare innovation and sovereignty.

Health hubs to watch:

Uppsala Health Tech Cluster, Sweden:

One of Europe’s largest life-science developments with a focus on production and R&D. It brings together diagnostics, consulting, biotech and medical technology.

old.uppsalabio.com

Leiden Bio Science Park, Netherlands:

The park unites companies from 14 nations and employs 19,000 people. It’s also home to big pharmaceutical players such as Johnson & Johnson and Belgian biotech Galápagos.

leidenbiosciencepark.nl

Medical Valley, Germany:

Focuses on medical technology and links 500 companies with 65 hospitals treating 850,000 patients per year. Home to Siemens Healthineers and Novartis Deutschland, among others.

medical-valley-emn.de

“Coronavirus has clearly shown us that we have a lack of independence in accessing critical healthcare resources,” says Etienne Vervaecke, general manager of Eurasanté, which oversees the business park where MDoloris Medical Systems is based and acts as an economic-development agency for the Hauts-de-France region. The area has struggled since deindustrialisation but it’s hoped that innovation clusters like this will transform the future of healthcare while giving the region an economic boost.

Eurasanté Bio-Business Park, a 300-hectare campus featuring a mishmash of architectural styles from slightly dilapidated brutalist to more contemporary offerings, is a Petri dish for public-private healthcare projects that span life sciences, research, academia and industry. If France is to bolster its healthcare prospects, it will need to lean on the Eurasanté campus, which is among the country’s most promising healthcare clusters. It includes eight hospitals, including the University of Lille Hospital, 50 research centres and 200 health companies; it’s easy to get lost when walking along its winding footpaths.

MDoloris Medical Systems wouldn’t be where it is without Eurasanté. The research that sits at the heart of its product took place at the University of Lille Hospital and the company grew up in the business park’s incubator, where young firms are nurtured with access to services, office space and external funding to eventually go it alone. The programme has been a marked success, at times acting as “a kind of ceo academy”, according to Dorothée Gueras-Tricart, who is in charge of innovation and entrepreneurship at the incubator. She meets Monocle at a lunch spot in the park to chat over a local cheese-heavy delicacy known as “Le Welsh”.

Eurasanté’s Bio-Incubator mainly focuses on two areas of healthcare: “medtech” (medical technology companies such as MDoloris) and “biotech”. The latter harnesses the power of biology to make breakthroughs in diagnosing and treating disease. Vervaecke argues that these companies should be viewed not just for what they do but the way they go about shaking up the industry. “Biotech should be seen more as an innovation model that is entrepreneurial and venture-capital backed,” he says. These leaner, faster companies have been at the forefront of healthcare in recent years, producing bigger results than the research and development labs at traditional big pharmaceutical companies, which often license a successful technology or simply acquire a company. Vervaecke cites a significant example of Pfizer developing its coronavirus vaccine by signing up with German biotech firm BioNTech.

Test-tube ready

Vaxinano CEO Didier Betbeder and team

Research machinery from the US’s Bruker

Testing, testing and then re-testing

Spend a day visiting medtech and biotech companies in Lille and you’ll receive an education in the gruelling process of getting new medical products to market. The risk is often high but succeeding brings with it substantial economic rewards and the chance to be a healthcare flagbearer for one’s nation. Among the promising companies monocle visits is Lattice Medical. Three of Lattice’s four founders are doctors working at the University of Lille Hospital and one of them shows up to meet Monocle wearing scrubs from his day job. The company is focused on advancing breast reconstruction as an alternative to silicone, using a non-toxic frame that encourages the growth of natural tissue before dissolving in the body. Another company, Vaxinano, specialises in nasal vaccines and is focusing on two parasitic diseases common in cats and dogs. Its founder, Didier Betbeder, tells Monocle that he thinks a human nasal vaccine could work against coronavirus and flu.

Yet the road to market can be long and fraught. Vaxinano needs €3m in funds to advance to the next stage of clinical trials, while Lattice Medical doesn’t expect to start production until at least 2025. Another company, Genfit, specialising in liver-disease treatment, dates back to 1999. Hairnets and disposable aprons are required on the tour of its labs, reached by long stretches of empty corridors, where white-coated staff carefully place small amounts of liquid into test tubes before examining them under microscopes. Genfit also failed one of its clinical trials – not uncommon in the industry – and had to adjust its focus. The move seems to have paid off: it recently signed a deal with a major French pharmaceutical company following promising results. “You shape things that don’t exist yet,” says Genfit’s chief strategy officer Jean-Christophe Marcoux. “That’s super exciting but it’s tough.”

Building a MDoloris monitor

Eurasanté’s Dorothée Gueras-Tricart

Eurasanté’s Bio-Incubator

Like almost everyone Monocle talks to, Marcoux says that funding is the hardest part of the puzzle in Europe, especially when compared to the US. He says that investors have “an aversion to risk”, while MDoloris’s Fabien Pagniez says that working in the US gives you a “full chance and full risk”, compared to a more cautious step-by-step approach in France. The difference in business culture means that companies will often set up in the US in search of a bigger, more lucrative market. France will clearly need to overcome that dynamic if it is to become a true world healthcare player, injecting more risk-taking into investor culture and ensuring that talent stays at home. Places such as Eurasanté will have an ever more important role to play. The men and women who run the park hope, among other things, to receive national “biocluster” funding from the government, which would last for a decade.

Research at Vaxinano

Beyond any geographic and strategic positioning of healthcare, though, Eurasanté’s general director Vervaecke knows that the sector can be a vehicle for change in Hauts-de-France. Inexorably linked to coal extraction and textile manufacturing – and the economic decline that came with deindustrialisation – healthcare is already a major employer in the region. But Vervaecke intends to help its prospects grow in the years to come, both inside and outside the park. “Healthcare is the main card that this region has to play,” he says. And it’s working.