Reportage 2. / Global

In safe hands

Digital archives are no replacement for the real thing – it’s only in a private visit to a secret hoard that history, humanity and passion are let loose to inspire, inform and entertain again.

Archives – whether put together by states or artists – are a portal to the past. But that’s not all they are: they’re also a reminder of what’s worked and what hasn’t, what we’ve had and what’s been lost. In that respect, perhaps they can also play a role in shaping our future by giving us an idea of where we should be going.

Bata Shoe Museum archive

Toronto

Archive contents: more than 13,000 artefacts

Elizabeth Semmelhack, senior curator, slips on a pair of white cotton gloves as she opens a set of drawers in the basement archives of the Bata Shoe Museum in downtown Toronto, one of the largest collections of shoes and footwear of its kind in the world. “Because we are so specialised, people often come to us first,” she says of how new objects are acquired, opening a drawer that holds the museum’s collection of shoe buckles, socks and stockings (including a fetching pair of black long-socks that once graced Napoleon’s feet).

“We’re not a museum that’s collecting Rembrandts where we have to fight with other major institutions at auction,” adds Semmelhack. “When this collection was conceived, footwear was deemed, even in costume collections, as something of an afterthought.”

Now numbering more than 13,000 objects, the collection was started by Sonja Bata, heiress to the Bata shoe fortune, which was established by her father-in-law, Tomas Bata, in the Czech Republic in 1894. The Bata Shoe Museum, designed by Raymond Moriyama, opened in 1995 as a permanent home for Bata’s collection. It spans ancient Egypt to basketball trainers, 20th-century high-fashion to ballet pumps, and includes the largest collections of moccasins, indigenous footwear and snowshoes anywhere in the world. Among the founding design principles of the archive was that each pair of shoes should be visible to curators and researchers inspecting the collection, rather than stored away in boxes behind a vault door or in sealed storage. “Walking into this room, it’s amazing to see everything all at once,” says Semmelhack, who has helmed the collection for 17 years. “I can be given a question and I can run downstairs and pick up a shoe. At a glance you can see how things changed, decade by decade, very quickly.”

While 89 per cent of the collection has been photographed and logged into the museum’s digital database, there is no replacement for holding an object, inspecting it and scrutinising the way it was made and how it was worn, says Semmelhack. “It’s economics, it’s globalisation, it’s fashion, it’s status, it’s gender binaries: all of these things are embedded in the shoes, in addition to the story of the individual who made them and the individual who wore them. I think that’s what makes looking into footwear so exciting.”

Helga de Alvear foundation

Madrid

Archive contents: up to 3,000 artworks

“It’s an illness, being a collector,” says Helga de Alvear with blithe candour. “I see something I like and I have no choice – I have to buy.” The German-born 81-year-old’s self-diagnosed ailment clearly brings her much joy. It has also made her Spain’s most avid art-buyer and one of the most popular figures on the international fair circuit. Her unashamedly insatiable appetite for contemporary art has seen her amass one of Europe’s largest collections – somewhere between 2,500 and 3,000 works by some 700 artists.

“Even I forget what’s in here,” she says as she escorts us through one of the four halls housing her collection. Abstract artist Andrew Pike, blockbuster polemicist Ai Weiwei, Pablo Picasso, Andy Warhol and, yes, Wassily Kandinsky (three of them): their works are all wrapped up in brown butcher’s paper and cloistered from view. The frames are so densely stacked along the walls that it feels like we’re wandering through a tightly wound accordion. Every compulsive purchase is packaged, posted and carefully placed. In some way it feels like the no-man’s land of post-modern expression; an egregious limbo for beautiful things.

Yet De Alvear is not hoarding one of the world’s most eclectic compilations for the sake of it: beneath the veneer of self-indulgence is a colossal gesture of generosity. “One day this whole space will be empty,” she says, with a hint of glee. She is, of course, alluding to the long-awaited extension to her eponymous foundation in Spain’s World Heritage listed city of Cáceres.

In 2003 she reached an agreement with the regional government to donate her entire collection to the city on two conditions: that it would bankroll a new gallery and then let everyone in for free. The Helga de Alvear Foundation opened inside a 3,000 sq m palace in 2006 but Spain’s subsequent financial strife saw the Mansilla & Tuñón-designed add-on put on hold. The stand-off saw De Alvear refuse to hand over the keys to her collection until the government lived up to its side of the deal. After years of political procrastination, construction has finally restarted.

“We’ll keep loaning out pieces in the meantime,” she says, pointing to the labels that include numbers, names and a nifty little photo to help locate artworks. “I truly believe that art should be free, which is why I’m giving everything I own to Cáceres.” For the time being, this cardboard-coloured purgatory waits patiently in the dark. “None of this should be exposed to light all the time anyway,” De Alvear says flippantly. “Sometimes art needs a rest too.”

UN Archives and Records Management Section

New York

Archive contents: more than 47,629 boxes of papers, documents and photographs

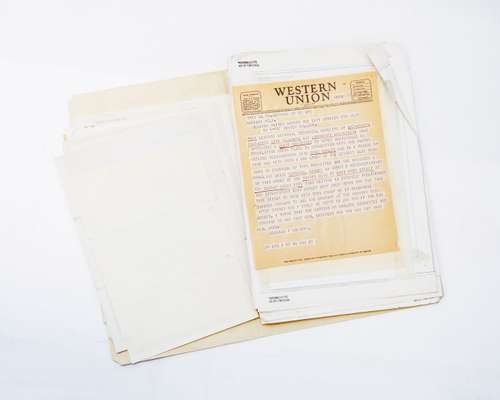

The UN loves its acronyms. Over at “Arms” – the Archives and Records Management Section of the organisation’s Manhattan HQ – a man sits in the reading room copying documents. Nearby, and beyond a nondescript door, is the peacekeeping organisation’s distinctly analogue archive, tracing the work carried out not just in its New York home but at permanent missions around the globe.

“We put the interests of the UN before our own countries,” says chief archivist Stephen Haufek. “I think that’s important to know for the archives as they were created by UN staff in service of the UN.” Surrounding Haufek are thousands of boxes stuffed with papers (there are 47,629 in total, including some at a second site in Queens) kept at a low temperature to stop them from warping.

One of the most fascinating aspects of the archive hails from the time when the UN had only just come into being after the Second World War and was still itinerant – moving around New York and holding meetings in Paris and London – as it waited for its modernist East River compound to be completed (the archive is actually located in a separate nearby building). Haufek and his fellow archivist Amanda Leinberger pull out some nuggets from that period, including the design work carried out by Oscar Niemeyer, the Brazilian wunderkind who was the youngest member of the UN HQ’s design team.

Another interesting part of the archive is the Serge Wolff Collection, named after an aide to Peter Noskov, an engineer on the HQ project. Wolff inherited Noskov’s photograph collection of everything from potential plots of land for the HQ to candid shots of the architects and imagery of the eastern part of Manhattan before development (it was a Greek neighbourhood full of slaughterhouses). “We normally don’t take donations from third parties,” says Haufek. “But it was such a strong collection.”

Blueprints, telegrams and letters to then first lady Eleanor Roosevelt sit alongside images from the UN’s precursor, the United Nations Relief and Rehabilitation Administration. These photos are still accessed by relatives of people interned during the war to learn about family members or organise reunions. The archivists’ work may focus on a bygone age but it’s also never done: the UN team faces the daunting task of digitalising records for public access and dealing with boxes as they come in. “It’s more than we can handle,” says Haufek, allowing himself a small chuckle.

Archivio Storico Capitolino

Rome

Archive contents: 82,500 monographs, 2,500 periodicals

Rome is of the most visited and most documented cities on earth. But beyond the layers of Roman history that every visitor and resident sees while traversing the city, there are also countless untold stories. An almost hidden doorway at Piazza dell’Orologio leads to an archive that provides the public with access to some of Rome’s many secrets.

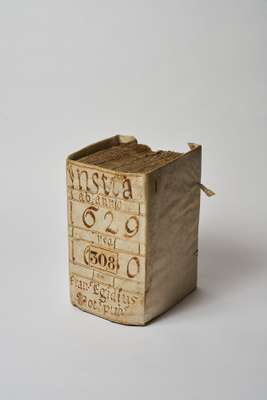

The Archivio Storico Capitolino has been at its current site since 1922 but the collection was started in 1871 as a means of collating and preserving documents relating to city-planning and governance in Rome. Today, what were the stately apartments of a catholic oratory designed by baroque master Francesco Borromini in 1637 house a priceless selection of 82,500 monographs and 2,500 periodicals. Maps, permits, notary documents and contracts, some of which date back to the 14th century, all have the Eternal City as their protagonist.

The heart of the archive is in Borromini’s splendid ovular Sala di Consultazione (consultation room), where Daniela Ronzitti is head of public services. “This place has an immensely practical use,” she says, referring to the 40 to 50 daily visitors, most of whom are here to look up historical planning documents. Ronzitti has near-encyclopaedic knowledge so “if an architect wants the 1850 drawings of a building on such and such number on whatever street” she’ll speedily dispatch the relevant folder. A lot of these records are digitised but if imagery is required you’ll have to call upon the careful hand of the archivist. “A lot of the maps and drawings have to be physically unfolded,” says Ronzitti.

The archive’s premises were fully restored in 2009, providing a comfortable setting for researchers. Outside there is a courtyard containing orange trees that host the chattiest of birds, which help to break the silence of the archives above. Urbanists and budding cartographers find gold here within the endless shelves of this little-known public facility. A 1929 map of Rome published by De Agostini reveals the many tramlines that traversed the centre – which today is woefully lacking in such convenience. Further back to 1830 and the General Map of the City of Rome shows how urban development was contained within the ancient Aurelian Walls. “The archives follow me when I leave work,” says Ronzitti, smiling. “I can’t stop thinking: ‘Do we have the records for that building?’”

Archi-depot Museum

Tokyo

Archive contents: 500 models

Tokyo has museums dedicated to everything from fireworks to socks but Archi-depot is the first of its kind in Japan: an open archive of architectural models by some of Japan’s best-known architects. It’s a unique concept, functioning both as a storage facility and an exhibition space, with 500 models – most on display but some in boxes – all kept at 20c and 50 per cent humidity.

The museum sits in a cluster of buildings owned by storage company Warehouse Terrada. Under the direction of its ceo, Yoshihisa Nakano, Terrada has gone beyond housing people’s superfluous possessions to art, wine and even film storage. So it made sense that Shigeru Ban, one of Japan’s most celebrated architects, should contact Terrada when he was thinking about what to do with the fragile architectural models that were cluttering up his office. Kengo Kuma, who has been working with Nakano on a redevelopment plan for the neighbourhood, got involved, as did another architect, Riken Yamamoto. The idea of making a place to preserve and display architectural models took hold.

“In Japan people tend to see architects as technicians and models as their tools,” says the museum’s deputy director Yukina Mori. “We realised that outside Japan, in places like the Centre Pompidou, people saw these Japanese models as artworks in their own right.” It helps that Japanese architects put more care into their models than anyone else. “Other architects will do drawings but they wouldn’t build models with this detail.”

Models by the three architects form the core of the archive; others rent shelves and place their models here to save them from damage in their studios. For visitors who are well versed in contemporary Japanese architecture, Archi-depot is a treat: there are many familiar buildings, such as Shigeru Ban’s Paper Church in Kobe (1995), and models span initial presentations to finished buildings, allowing people the chance to see an architect’s original intentions.

Even if you know nothing about architecture there is something thrilling about seeing buildings in miniature. Torafu Architects’ 1:50 scale model for a Fred Perry shop in Harajuku comes complete with mini staff, customers and T-shirts. There are models of projects that never progressed to bricks and mortar and private houses by the likes of Kengo Kuma that would be out of bounds in real life. Models can show what is possible in architecture and, in some cases, what isn’t. “If you can’t build it as a model, then you probably can’t build the real one either,” says Mori.

Real Fábrica de Cristales, La Granja de San Ildefonso

Spain

Archive contents: 4,600 moulds

It was a royal mess. Centuries of artisanal heritage strewn across the floor like a perfunctory footnote. Spain’s Real Fábrica de Cristales de La Granja, the world’s only functioning royal glass factory, was struggling to keep its furnaces blazing. Its 4,600-plus collection of steel glass-moulds – said to be Europe’s biggest – were left to accumulate dust.

Established by King Felipe V in 1727, La Granja once sparkled with the avant-garde spirit of the Enlightenment. At its zenith this vast glassware factory was responsible for some of the world’s most sought-after copas (wine glasses), tulipas (lamps), licoreras (decanters) and arañas (chandeliers), all adorning palaces and prestigious homes in Europe and across the Americas. By 1980 these halcyon days of royal prestige had dimmed into distant memory; four decades of dictatorship, royal exile and the new urgencies of a nascent democracy forced the factory’s closure and it was reduced to a mere nesting ground for a seasonal population of unsympathetic storks.

For the town’s residents, the 25,000 sq m complex was hard to ignore. A collective of artisans banded together to form a foundation, moving in and setting up a glass-making school in 1990. With support from the cultural ministry it has been slowly stoking new fires of fortune.

Part of this effort has involved recovering the vestiges of other shuttered glass-making factories in Spain. “Some of the moulds were salvaged from scrap-metal deposits,” says Elena Arenal, the factory’s communications chief. “Thankfully someone had the sense to bring them here.”

Industrial designers Marta Alonso Yerba and Imanol Calderón Elósegui from Mayice studio also came knocking. The pair scoured the warehouse, selecting 22 classic moulds to create a collection of 13 hanging blown-glass lamps. “We wanted to use the age-old forms but cast them in a new light,” says Yerba. “But this meant getting on our knees to sort through the clutter,” adds Elósegui.

Their collection’s success shone a light on the archive’s untapped potential. As visits from other designers increased, bringing order to the chaos became a way to illuminate the path forward. Today the forensic effort to polish and catalogue more than 4,600 moulds continues, examining clues such as screw types and serial numbers to ascertain the story behind each piece. As method replaces madness, the future has promise: order, a clearer vision and a warehouse full of possibilities.

“We’re delighted to receive anyone looking to create something; this treasure is here to be shared,” says Arenal. “It means we’ll endure too.”

Forbes Pigment Collection

Massachusetts

Archive contents: 2,500 samples

Up on the fourth floor of the Harvard Art Museum in Cambridge, Massachusetts, you won’t be able to find any Helladic pottery or works by old masters. Instead you’ll find a narrow hallway lined with glass cases filled with more than 2,500 pigment samples dating as far back as ancient Rome. They include Vantablack, Stuart Semple’s Pink and Black, ochres from Australia and dyed yarn samples from the Zapotec weaver Porfirio Gutiérrez, all arranged by colour. This is the Forbes Pigment Collection, part of the Straus Center for Conservation and Technical Studies at the museum.

“The centre looks at how an artist made a work of art and what materials they used, so that we can then understand what the work might have looked like when it was first made and what has changed over time,” says Narayan Khandekar, the centre’s director. While much of a pigment’s data can be entered into an online catalogue, when dealing with the subtleties of a work of art nothing can beat getting your hands dirty. Pigments in the archive are often used to calibrate scientific instruments such as the Raman spectrometer (commonly used in chemistry to identify molecules) or to make sure the infrared spectrometer is up to snuff before starting any analysis.

The collection was the vision of Edward Waldo Forbes, director of the museum in the early 20th century, who collected pigment on his travels and even tried growing some at home in order to create a library of standards that he could use to understand works of art. The collection’s jars, tubes, bags, vials and even stones act as time machines that reveal how a painting looked centuries before and what paints were added in earlier restorations. They also help with spotting the odd forgery or two.

It was this task that breathed new life into the archive 10 years ago when Khandekar and his team were tasked with confirming the authenticity of three never-before-seen Jackson Pollock paintings – which spurred them on to collect modern samples. Working with pigments from the collection, they were able to show that some of the paint used wasn’t available until 30 years after the artist’s death.

While searching out fakes may seem like it would be the most sought-after, glamorous part of the job – and it certainly garners attention for the centre’s work – it doesn’t cut the mustard for Khandekar. “The real pleasure is actually understanding how great artists paint. We want to look at the real thing.”

Swire Archive Service

Hong Kong

Archive contents: 130,000 photographs, 4,000 boxes, 4 terabytes of digital records, 1,000 film reels

In October a box arrived at the Swire Hong Kong Archive Service containing an unpublished autobiography. Images in an Oriental Sky by Ray Farrell begins with tales of flying “the hump” during the Second World War – Allied flights over the Himalayas to resupply the Chinese army – before the late US pilot co-founded Cathay Pacific and later sold the Hong Kong airline to Swire. The rare manuscript has now made its way into the repository: archive-speak for a bank vault-style room with climate control and security cameras, designed to keep valuable paper and prints fire proof, mould proof and idiot proof – bags and bottles must be left outside.

“The ‘dusty archive’ is a misnomer,” says archivist Matthew Edmondson, while standing in his immaculate Aladdin’s cave that opened in 2015. White cotton gloves would barely pick up a grey particle were they not another TV fallacy: cotton can lead to inadvertent curling so paper is best handled with clean – but not moisturised – hands. The Brit does don blue surgical gloves for the thousands of photographs and hours of film under his protection but not everything is so valuable. A bubble-wrapped model aeroplane, two metres long, has landed on the floor. “I didn’t know it was going to be so big,” says Edmondson, who must also juggle plenty of other records that arrive from across the diverse conglomerate, which spans property, shipping, sugar and bottling.

He clearly enjoys having his hands full with aviation history and speaks enthusiastically about early timetables and safety cards showing the location of the onboard machete (in case of going down in a jungle). He pulls out a drawer to reveal his favourite items: technical drawings of aeroplane livery from the 1950s. “They are beautiful, and hand drawings are not something we will be able to capture in the same way in future.”

Swire’s management decided to establish an archive in 2011, when it started planning for the 150th anniversary of its operations in Asia. Its history in Hong Kong stretches nearly as far back as the city’s founding in 1842, although most of the archive is postwar. Today it is not just a reference point for academics: marketing, design and communications teams often pop by looking for inspiration. And recently Swire’s property arm used images of vintage sugar packaging to decorate its new co-working space nearby. “It’s a working archive and that’s what’s fun about business archives,” says Edmondson. “We try to make it add value to all parts of the business and that means every day is different.”

Abboudi Abou Jaoude’s Arabic film poster collection

Beirut

Archive contents: 20,000 items

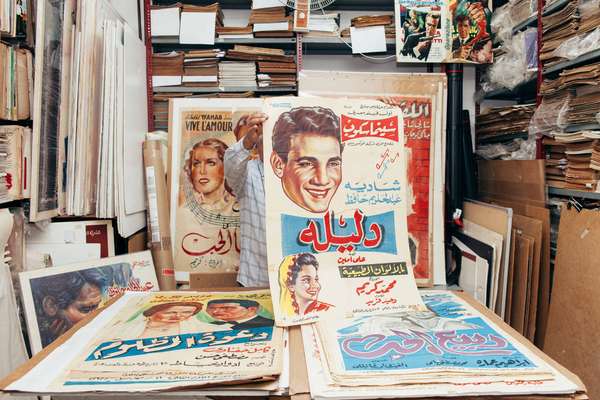

Every Saturday in the early 1970s, Abboudi Abou Jaoude would walk west across Beirut visiting the 30 or so cinemas once found in the Lebanese capital and planning what films he might watch next. “It would take me four or five hours,” he says. Why? Along the way he’d be collecting posters advertising the US films of the day. He particularly coveted anything starring Steve McQueen or Clint Eastwood.

In among them, cinema staff would occasionally give him posters for Arabic films. “At first I took them and I left them,” he says, gesturing as if to toss an invisible version aside. But over time his interest in local cinema grew and, with it, his poster collection. Today it is one of the most comprehensive archives of film paraphernalia in the Arab world, incorporating about 20,000 posters, photos and pamphlets that are all stored in underground rooms in the village-like district of Ras Beirut.

“In the 1950s most of the Arabic movies had dancing and singing, like European films,” says About Jaoude, standing between two of the archive’s floor-to-ceiling shelves, the distinctive smell of worn paper in the air. “In the 1960s they had espionage – something like James Bond. Then in the 1970s most of the Arabic movies were about sex. They had the same themes that you would find in foreign films.”

Even as Lebanon descended into civil war in 1975, Abou Jaoude continued collecting. He stored some of his posters at his grandfather’s home in the mountains, while others were stowed four floors below Hamra Street, 10 minutes’ walk from his current archive.

Although he lost some posters to damp, his collection endured – mostly intact – during the war years. What remained outside his hands was less fortunate. “People didn’t know the value of these things,” he says. “Most of the Lebanese theatres were destroyed.”

Although there are non-governmental organisations attempting to catalogue images and photos, Lebanon has no official cinema archive; Abou Jaoude remains an unofficial gatekeeper. His favourite item in the collection is a poster for the 1940 film The Thief of Baghdad, which hangs above a cluttered desk. “I want to let young people see what we have because they just don’t know,” he says. “In these things we can find the way we used to live in the 1960s. It is our heritage.”

Tomás Saraceno’s spider-webs collection

Berlin

Archive contents: 60 webs, 100 ‘maps’

Beyond the sculptures and assistants working in Tomás Saraceno’s post-industrial studio complex in Berlin’s eastern Treptow district is a special space. It’s a room in which spiders big and small, living in carbon-fibre frames, spin webs alone, in sequence or in groups.

It’s a tough space for arachnophobes: some of the eight-legged creatures are much larger than the spiders we all find spinning webs in corners at home. But the webs are fascinatingly delicate and vary dramatically in form. And the Argentina-born artist always reminds fearful visitors that we co-inhabit spaces with spiders and always have. “Spiders always find a way to live with us,” he says. “The first spiders were spinning webs 140 million years ago.”

Beyond encouraging spiders to spin (and experimenting with how different species spin together), Saraceno has been archiving their spun habitats for about eight years. Once a web is “complete” (spiders have a lifespan of about 18 months), it’s carefully cleaned and hermetically sealed in its frame; about 60 of these are now on file. In addition there are about 100 “spider maps,” which have been created by colouring the web and inserting a paper through it. The results are two-dimensional topographical images.

“We keep the webs together as a scientific collection,” says Ignas Petronis, who oversees the archive. So while the pieces have appeared as art objects in venues such as the Louvre in Paris, they’re also considered scientific artefacts and have been lent to venues including the Natural History Museum in Frankfurt.

Saraceno has been fascinated by spiders and the universes they spin for most of his life. “It started when I was a kid. I would always go to the attic of my grandmother’s old house and watch these wonderful webs,” he says. Anyone familiar with the artist’s web-like “cloud city” sculptures can see their arachnoid inspiration but these days the spiders and webs also connect to Saraceno’s focus on seeing the world from a non-human point of view. “What I’m doing in the end is just giving space to another species,” he says.

The archiving will continue, with digitised and scanned webs ultimately available to researchers online; the studio is currently co-authoring papers on webs with institutions such as the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (Saraceno’s alma mater) and Berlin’s Max Planck Institute. “It’s a fascinating practice: a form of artistic research intersecting with science,” says Petronis.