Considered opinion / Global

Taking the pulse

From probing the state of globalisation to exploring the political landscape in Mexico – via tips about how not to lose your mind during this particularly intense news cycle – our writers weigh up the issues of the year ahead.

1. What next for globalisation? (politics)

by David Miliband

The UK’s former foreign secretary ponders the state of the global political and economic order. His conclusion? The mass movement of people heralds a bumpy road ahead for all involved.

In 1920, John Maynard Keynes sat in his living room in Bloomsbury drinking Indian tea and marvelling at the wonder of globalisation. He remarked how a citizen of London could enjoy the fruits of the world delivered to his door with an ease and speed never before imagined. He claimed that the internationalisation of the world’s social and economic life “was nearly complete in practice”.

Little did he realise what was to come: a veritable revolution of hyper-connectivity across the globe that now dominates politics. The global society may have arrived but with it has come a revolt against globalisation – and in the very countries in the western world that have been the driving force behind its development. Globalisation has proved itself enriching, empowering and inspiring but also unequal, unstable and insecure. In this vortex lies the future of politics.

You can see how politics on the left and right has been turned upside down by it. On the left, globalisation is seen as the enemy of equality; on the right it’s viewed as an enemy of social order. “Globalist” has become a term of abuse; migrants and refugees are labelled as a Trojan horse for terrorism. Far from embodying the future, internationalists are called citizens of nowhere. And suddenly China is the leading status quo power, its president travelling to Davos to defend the global system, while Donald Trump uses his inaugural address to set out a revisionist manifesto that pulls down the pillars of the post-Second World War world.

It is vital to take a deep breath and take stock. Globalisation is obviously a victim of its failures. The financial crisis, rising inequality, the wars in Afghanistan and Iraq, the failure to match trade adjustment with trade agreements and the struggle for successful integration of some immigrant communities have all drained support for international co-ordination and co-operation. Equally, globalisation is – in an ironic way – a victim of its successes. Those who framed the postwar order wanted to spread markets; they have succeeded beyond their aspirations. But that has shifted the relative balance of economic power in the world. They wanted to spur innovation – again, a huge success – but the price is a hollowing out of the middle class. They wanted to connect the world – again, remarkable progress – but the downside is that any system is only as strong as its weakest link.

At the heart of the globalisation conundrum is that economics and politics, for a long time in harmony, are now in discord. While the global economy is boosted by migration, the politics of that migration is tearing western societies apart. While global economics is stabilised by international co-operation and mutual support, local politics is – as the euro crisis shows – resistant to this bargain. While global economics demands investment in the young and the retraining of the middle-aged, local politics is driven by the high voting rates of the old. While the expansion of global markets has led to a gradual reduction in global economic inequalities, local politics is more concerned with inequality within nations than between people across the world.

Election results bear out this tension. The 2,600 US counties that voted for Trump out of a total of 3,000 account for just 36 per cent of the national income. The social and economic bargain that underpins any sustainable system of governance has broken down for significant sections of the electorate. The market has essentially overshot, threatening its own sustainability.

Extreme poverty – living on less than €1.60 a day – has been reduced from 72 per cent in 1950 to just 10 per cent today. In countries such as China, South Korea, Brazil and Mexico, widespread hardship at the end of the Second World War has given way to a burgeoning middle class today. And for the super-rich, this growth has been similarly lucrative over the past three decades. Since 1988 the top global 1 per cent have seen their real incomes rise by more than 60 per cent, dwarfing the gains of the industrialised middle class, whose incomes have remained flat in real terms. So there is a huge priority: globalisation needs to be made fairer if we are to defend its gains.

Globalisation without rules is not viable, without institutions it’s not manageable and without fairness it’s not legitimate. The agenda writes itself, even if the policy details are difficult, be it housing inequalities in the UK that prevent the next generation from obtaining wealth and opportunities, wage inequalities in the US that create a vicious cycle of low demand and low mobility, or employment inequalities in France that lock people out of the labour market.

The rise of populism comes in many guises. Populism on the right has taken real anger at growing social inequality, and economic and social loss among working and middle-class people, and channelled it at some of the most vulnerable people in the world, particularly refugees. The treatment of refugees is a barometer for the character, stability and values of the international system. The danger is that new walls to keep people out will come to define the first half of the 21st century, much in the way that the Iron Curtain defined the second half of the 20th.

Refugees – the people forced to flee their homes due to conflict and persecution, rather than choosing to do so for economic gain – are a test case for whether the idea of the international community is meaningful. The rights of refugees were enshrined after the Second World War and were part of the package of reforms that civilised the global order.

The stories of these people – bakers from Damascus whose houses were bombed, girls from Nigeria chased from their schools, religious and political minorities persecuted for their views – is heart-wrenching. If we cannot help them, across lines of race and religion, then we will not be able to preserve the best of the global system that has been painstakingly built – and the global values that hold the best hope for humankind.

About the author: David Miliband served as UK foreign secretary between 2007 and 2010. He is president and ceo of the International Rescue Committee, based in New York.

Reading list

1. What is Populism? by Jan-Werner Müller

2. Rescue: Refugees and the Political Crisis of our Time by David Miliband

3. Power and Plenty: Trade, War and the World Economy in the Second Millennium by R Findlay and KH O’Rourke

4. The Globalization Paradox: Democracy and the Future of the World Economy by Dani Rodrik

5. The Great Convergence: Information Technology and the New Globalization by Richard Baldwin

2. How to stay news free (media)

by Monica Heisey

Tired of the constant chatter and an avalanche of bad news, our writer has decided to go cold turkey: she’s throwing away her iPhone and ignoring Twitter. For a whole day, no less.

The year 2018 is going to be amazing. Here is how I know: at midnight on 1 January I’m going to cancel my subscriptions and delete all my apps. I’m going to throw my iPhone in a river and burn every newspaper and magazine in my house. In the morning I will wake up joyful, ready to spend 24 hours as Someone Who Does Not Read The News.

I have already spent too much of my one and only life consuming horrible news, then horrible opinions about horrible news, then horrible responses to the horrible opinions about the horrible news. Like any human with a working soul, I have been crushed by 2017’s news cycle. The sheer volume of problems to be solved, of steps to take and of fake and real crises to wade through has motivated and exhausted me in equal measure. I have taken breaks, of course. I’ve announced my intention to quit the news and then binged on social media for hours, trawling acquaintances’ posts about gender-neutral bathrooms or an uncle’s solution for the situation in North Korea. This year, for one day, it stops.

I cannot start 2018 as the cynical withered husk that 2017 has made me. There is simply too much to do. And so, instead of cycling daily through a catalogue of terrors – the scope of which I can never truly grasp, solutions to which are completely out of reach – I will simply… not. I can only imagine how great it will feel to wake up, make some coffee and just Not Know.

Instead I will take up hobbies. I will learn to make things with my hands. I will grow my own food and preserve it. I will become an excellent correspondent, writing beautiful letters on stationery imported from the UK, one of many countries I will know nothing about. Have they decided on how to leave the EU? I will have no clue. I will only be able to report on the quality of British paper stock. Maybe I will take up bird-watching. With the time I will save not reading, watching or commenting on the news, I can and will learn Esperanto.

My thumbs will stop aching. My spine will straighten. “What are you doing?” People will ask. “You look so… hydrated.” I will smile a knowing smile and say nothing about climate change because I will have no idea which bit of the Arctic has just fallen into the sea. “Did you hear what the president said?” they will ask. I will laugh a wise little laugh to myself.

Is this overly optimistic for a single 24-hour period? Maybe. All I’m saying is, we can’t know until I’ve tried. The idea is more relaxing than a spa treatment, more luxurious than any bathrobe; I’m going to wrap this carefree life around me like a blanket, warming my hands by the fire of not having an opinion about gun control. I’ll light a scented candle that smells like Life Before I’d Heard The Word “Covfefe”.

Of course, I cannot hide forever. Eventually (a day is a good start, isn’t it?) I will have to put down my birding binoculars and encounter the news, real and fake. Knowing that the other 364 days will be filled with fear, exhaustion, sadness, rage and arduous, long-term work will only make this day of respite more special. I’m going to briefly slip into a bath of ignorance and wait until I prune.

About the author: Heisey splits her time between Toronto and London. She writes comedy for TV and “bizarre little humour pieces” for The New Yorker, The Guardian and The Globe and Mail, among others. Her first book, I Can’t Believe It’s Not Better: A Woman’s Guide to Coping with Life, is out now.

Reading list

1. The Art of Thinking Clearly by Rolf Dobelli

2. PG Wodehouse: A Life in Letters, ed by Sophie Ratcliffe

3. The Sibley Guide to Birds by David Sibley

4. Irresistible: The Rise of Addictive Technology and the Business of Keeping Us Hooked by Adam Alter

5. Toast & Jam: Modern Recipes for Rustic Baked Goods and Sweet and Savory Spreads by Sarah Owens

3. Mexican populism? Not quite (politics)

by Genaro Lozano

The upcoming elections mean a welcome change in Mexico but can the charismatic presidential frontrunner finally make it over the finishing line?

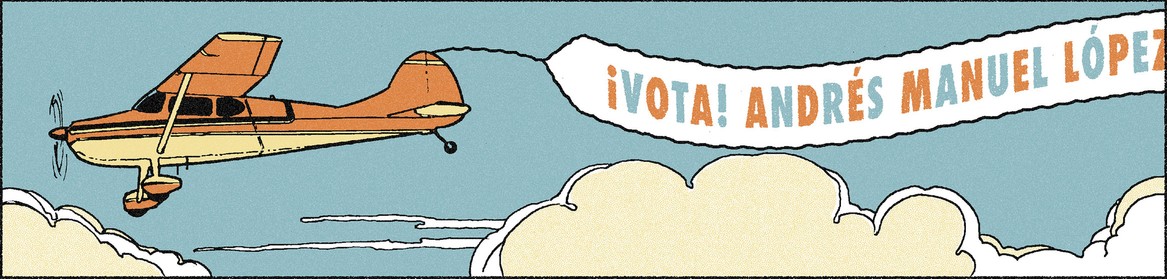

Next year Mexicans get to voice their political discontent at the ballot box, amid stories of corruption at the highest level, spiralling crime levels and a severe human-rights crisis. Mexico is a regional economic powerhouse and the outcome of this election will have consequences that will ripple beyond North America’s borders. Until the start of the millennium it had endured seven decades of one-party rule but there’s a strong chance that the country will lurch away from the traditional conservative leaders it normally chooses and cuddle up to a leftist. It’s a move that would run counter to the direction in which the rest of Latin America is moving. Many fear that Donald Trump and his anti-Mexican rhetoric have paved the way for another populist south of the US border. But although much of the press – both national and international – has been quick to label the current frontrunner in the July 2018 race as such, the fear is misguided at best. Indeed, unlike Trump, poll-topper Andrés Manuel López Obrador – widely known as “Amlo” – is a career politician who has been a member of three different political parties in Mexico.

Unlike Trump, Amlo has already held public office, including running Mexico City, the biggest and most important metropolis in Latin America. Also unlike Trump, Amlo is not running a political campaign with a xenophobic message. He has publicly defended free trade and Mexico’s membership of the North American Free Trade Agreement (Nafta). And while he may have criticised the latter for not fulfilling its promise of reducing the salary gap between workers in Canada, the US and Mexico, he has never threatened to sink it.

Besides the unexpected challenge of trying to solve Mexico’s most important trade agreement, the country also faces domestic problems that have made the 2018 election a critical moment. Corruption, inequality, violence, insecurity and a war against drug cartels continue to threaten a fragile democracy. A recent survey by Pew Research Center shows that only 6 per cent of Mexicans are satisfied with the way Mexican democracy – and, by proxy, its political class – is working. This reality has made corruption and economic growth two of the key issues of the election; the presidency of Donald Trump is a third one. For his opponents Amlo represents a bogeyman, a populist and a dangerous leader who could reverse Mexico’s integration into the global economy by implementing a nationalistic, protectionist economic plan. But Amlo’s economic platforms in his 2006 and 2012 presidential runs were closer to those of Chile’s outgoing centre-left leader Michelle Bachelet or Bernie Sanders’ platform in the 2016 US election than to socialist Nicolás Maduro in Venezuela or even Trump’s nativist, anti-free trade agenda in the US.

Despite all this, every six years there tends to be a fresh round of headlines comparing Amlo to Hugo Chávez, and slogans calling him “a clear and present danger to Mexico”. The story is getting old – but, then again, so is Amlo. At 65 he would become Mexico’s oldest elected president in a country where more than 37 million people are younger than 29 and 14 million are set to vote for the first time in 2018. And yet despite his previous two unsuccessful presidential bids, Amlo’s recent campaign seems stronger and more disciplined than in the past. Since losing the elections of 2006 and 2012 he has created a new political party, Morena, that has become Mexico’s strongest leftist political force, dividing the left and displacing the progressive prd. Since migrating from social movement to party in 2014, Morena – similar in style to Spain’s Podemos and Greece’s Syriza – has gained broad electoral support, mostly because of Amlo’s charisma and style. His popularity, especially among the poor and lower-middle classes, is considered a danger to Mexico’s elites and corrupt political ruling class.

If Amlo wins the presidency there will be two alpha males governing Mexico and the US – and many expect conflict. However, Trump’s presidency hasn’t radicalised Amlo. On the contrary, the Morena candidate has offered the US president a conciliatory message. In his book Oye, Trump (Listen, Trump) Amlo writes about Trump’s rhetoric and offers some idea of what to expect from the bilateral relationship if he wins the Mexican presidency. Amlo talks about strengthening Mexico’s consular network in the US, launching a PR campaign directed at the American people and stressing how important migration and trade with Mexico are to the US economy.

In next year’s election the ruling pri party will be the incumbent – but also a party facing severe questions over its legitimacy and a seemingly insurmountable dent to its PR image after a wave of scandals. The presidency of Enrique Peña Nieto has fallen short of fulfilling its promises and has been denounced for spying on political activists and opposition leaders, creating “alternative facts” regarding the disappearance of 43 students in the state of Guerrero, and for a weak defence of Mexico’s dignity in the face of Trump. In any other democracy, a government with a less than 20 per cent approval rating would probably face defeat in an election. But the pri is a formidable political machine – and an expert at rigging elections.

What also needs to be taken into account is that Amlo can be adept at destroying his own electoral appeal. Just like Trump, he has zero tolerance for criticism and often dismisses his detractors as “sold to the political mafia that rules Mexico”. His greatest challenge is to steady his nerves and surround himself with a new generation of leftist leaders rather than the usual suspects who have accompanied him on his unsuccessful runs. He has awakened the possibility of real change in Mexico but the reality is that even if he wins, Mexicans have been promised radical change before and they’re sceptical. Amlo deserves his chance – but he’s no Messiah. Much less a Mexican Trump.

About the author: Genaro Lozano is professor of political science and international relations at Universidad Iberoamericana. He’s also a political analyst for Reforma newspaper and Foro TV.

Reading list

1. Mexico: Democracy Interrupted by Jo Tuckman

2. El Narco: Inside Mexico’s Criminal Insurgency by Ioan Grillo

3. Mañana Forever? Mexico and the Mexicans by Jorge G Castañeda

4. Opening Mexico: The Making of a Democracy by Julia Preston and Samuel Dillon

5. Mexican Messiah: Andrés Manuel López Obrador by George W Grayson

4. Power play (advertising)

by Paula Scher

A principal at design consultancy Pentagram ponders the dynamics of advertising. Sex clearly sells but at what price – and is it one that we’re really willing to pay?

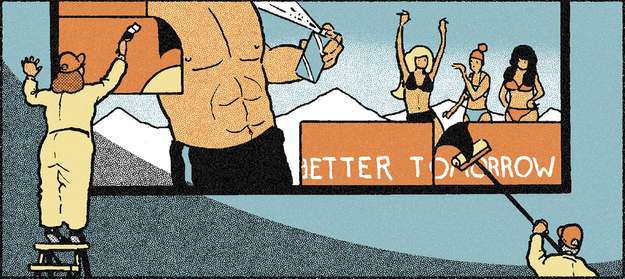

Sex has been in advertisements for as long as I can remember looking at them. Fashion has always created role models – whether you wanted to look like Audrey Hepburn, Marilyn Monroe or Jackie Kennedy – and with that territory came the idea of provocative innuendo. How raunchy the sex has been has depended on how society has accepted this information. It’s hard to think of an age when sex wasn’t used in some capacity, unless you trace its history back over 100 years – and even then it was often lurking, albeit in a much subtler form.

German-Australian photographer Helmut Newton – famed for his black-and-white fashion photography for Vogue and other publications – was overtly sexual in his work back in the 1970s and 1980s. And then there was Calvin Klein in the 1990s, who was all about the aesthetics. The photos taken for CK by Bruce Weber, for example, showed perfectly sculpted muscular bodies in skimpy underwear. They boldly faced the camera head on. It was gorgeous and it raised the bar to a level that other people then tried to match – often with less taste.

These photos may have ruffled some feathers at the time but, historically, such prudishness has always been prevalent in the US. Just look at the film industry: there was a whole code in place to prevent raunchiness during the era of silent films and early talkies.

Both men and women want to feel desirable – and in different ways – so they look at fashion advertising as something that they want to relate to in terms of their own sexuality. Women who like looking at Dolce & Gabbana adverts have a different image of themselves compared to women who look at Prada adverts; men who are attracted to Calvin Klein adverts have a different sensibility to those who like Versace adverts. It’s the way you perceive yourself physically and culturally; the advert image is inexorably linked to self-image.

Fashion advertising spreads itself all over the map, from aspirational imagery to sexual provocation. If it’s badly done then it’s offensive but if it’s done beautifully, it’s art. You can’t generalise fashion and sex because it’s really about different socioeconomic groups and what they’re comfortable looking at.

If you take advertisements in Vanity Fair and Vogue as examples, they’re not the same as those that run in the mass-market magazines that the Meredith Corporation here in the US puts out. An urban audience, too, will have a different response to a suburban one. There’s even a form of millennial advertising that shies away from sex altogether because it doesn’t sell in that capacity. Young people are buying products online, meaning they don’t consume fashion photography in the same way and would rather just look at products.

All of this comes to a head when you consider the sexual allegations that have been swirling around recently. It may well lead to editors and photographers exercising more caution in the short term but it won’t result in any lasting change. Plus, what has been happening isn’t really about sex: power and sex are not the same thing.

If you look at Alabama politician Roy Moore – accused of inappropriate sexual behaviour with at least one minor – that’s power. If you take comedian Louis CK – who admitted to allegations that he behaved inappropriately in front of female colleagues – that’s about the power to behave improperly more than the inappropriate behaviour itself. And if you look at Harvey Weinstein, that’s the ultimate example of complete and total sexual harassment, an abuse brought about through power.

I experienced some of this behaviour earlier in my career as an art director in the music industry – with people who weren’t famous – and I know it has nothing to do with sex itself: it’s about using your position to gain an advantage. This abuse can’t be separated from the proliferation of sex and innuendo in advertising but such ads can’t be blamed, in and of themselves, for the behaviour of bad men.

The issue becomes much more interesting when we ask this: how can we create a space for sexy or provocative fashion ads without encouraging the abuse of power?

About the author: Paula Scher has been a principal of Pentagram in New York since 1991. She has worked on design identities, packaging and branding for clients such as Bloomberg, the Sundance Institute and the High Line.

Reading list

1. Calvin Klein by Calvin Klein

2. Helmut Newton: Sumo revised by June Newton

3. The Erotic History of Advertising by Tom Reichert

4. Mid-Century Ads by Jim Heimann and Steven Heller

5. Contagious: Why Things Catch On by Jonah Berger

5. Hitting the road (driving)

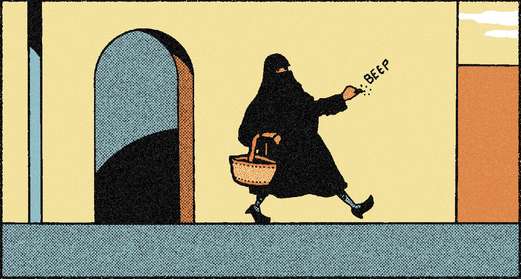

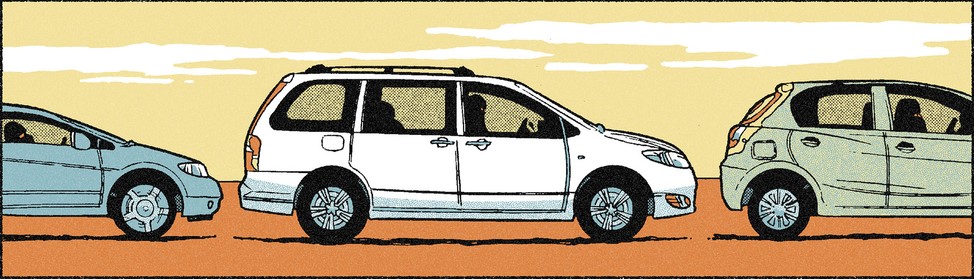

by Manal AlDowayan

The lifting of the driving ban for women in Saudi Arabia means so much more than just being able to drive a car: it’s a real game changer.

“They’re allowing us to drive,” my sister said, shouting down the phone. It was 06.00 in London – where I am currently studying – so I wasn’t quite prepared for an emotional conversation before having my first cup of coffee. “What do you mean, ‘allowing’?” I asked. “It’s over,” she said. “They announced it this morning.”

Over the past few months Saudi Arabia has witnessed a series of rollercoaster mornings like that one. The day begins with a governmental decree on an issue deemed untouchable for the past 30 years, followed by three days of intense social-media hysteria. Dramatic shifts in governmental appointments, the removal of religious policing and a sincere attempt at eradicating corruption have been part of this new equation and I knew that a major announcement was planned for Saudi Arabia’s national day at the end of September, which was when my sister had called. What I wasn’t prepared for was the lifting of the ban on women driving in the kingdom, which will come into force in 2018. It’s a move that promises to change the lives of Saudi Arabian women – for so long mostly invisible – forever.

The historic day of the announcement also made me think about my own artwork. I constantly address invisibility and absence in my artistic practice and a few years ago I produced a project entitled Crash, which looked at the strange phenomenon of Saudi female teachers who kept dying in gruesome car crashes across the country. The project highlighted the way in which these tragedies are memorialised, where the events unfolded and how the details were recorded. I soon discovered an intentional erasure of female names in the media coverage of these accidents.

The story of these deaths has its roots in rural Saudi Arabia, where a village requiring a girl’s school is provided with a state-funded building with two teachers and a principal to run it. Female teachers – education, like everything else, is divided along gender lines – need to commute for six hours a day from the big cities in order to teach at these schools. And still need to be driven, often in substandard vehicles or by poor drivers, which is the reason for many of the deaths.

In Crash I focused on how Saudi media covered the accidents and what the public experienced while consuming this media. Looking at newspaper articles I found that they would typically list the names of all the men involved but never the names of the deceased teachers. This is the result of a custom of hiding the names of women because they are associated with the shame of unveiling. The religious “awakening” of the 1970s in Saudi Arabia had encouraged the idea of the sacredness of women: their bodies, their faces and their names. The act of seeing them had become closely linked to dishonour. So how would lifting the ban on driving impact these teachers?

According to King Salman bin Abdulaziz Al Saud’s decree, as of June 2018 women will be able to drive in Saudi Arabia, creating a large shift in the status of women. Not only because they will be in control of their safety and mobility but because the embarrassing and demeaning debate on the ability of a Saudi woman to be a contributing citizen, or her right to be treated as an adult, is placed at the forefront of the national dialogue.

Clearly the symbolism of being behind the steering wheel, rather than in the backseat, has far- reaching implications that go beyond the decision to lift the ban on women driving in Saudi Arabia. Women will hopefully gain a prime seat in national transformation and be allowed to actively participate. My hope is that those brave teachers who have been invisible for so long will stop dying on remote roads. And that they will live to tell the story of a time when they were not allowed to operate cars – as they drive their granddaughters to school.

About the author: Manal AlDowayan is a contemporary artist from Saudi Arabia. Her artistic practice revolves around themes of active forgetting, invisibility and collective memory, with a focus on the state of Saudi women and their representation.

Reading list:

1. Invisible Man by Ralph Ellison

2. A Most Masculine State: Gender, Politics and Religion in Saudi Arabia by Madawi Al-Rasheed

3. Contemporary Arab Thought: Cultural Critique in Comparative Perspective by Elizabeth Suzanne Kassab

4. Uncommon Grounds: New Media and Critical Practices in North Africa and the Middle East ed by Anthony Downey

5. Women’s Rebellion & Islamic Memory by Fatima Mernissi